“When prevention is buried, we dig.”

“Not a rebellion—but a remembrance. A return to the root.”

By Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

Investigative Journalist | Public Intellectual | Global Governance Analyst | Health & Social Care Expert | International Business/Immigration Law Professional

Executive Summary

The Root Cause Revolution: A New Paradigm for Healing, Vitality, and Human Longevity

This 12-part compendium offers a radical yet evidence-grounded reimagining of health—moving from the reactive, symptom-suppressive model of modern medicine to a proactive, systems-based approach rooted in biology, resilience, and regeneration. Synthesizing cutting-edge research across functional medicine, neuroscience, endocrinology, nutritional biochemistry, and psychophysiology, this work unveils how the body heals not through isolated interventions but through restoring its natural networks of balance.

Part 1, The Root Cause Revolution, sets the foundation by exposing the deception of symptoms and the chronic failure of conventional diagnostics to address true origin points of illness. Functional medicine is introduced not as an alternative, but as a deeper logic—one that follows the first domino to its source, often in the gut, brain, or mitochondria.

Part 2 explores sleep as the body’s master regulatory system. Hormonal homeostasis, fat metabolism, immune recalibration, and cognitive resilience all hinge on the quality—not just quantity—of sleep. In Part 3, the gut emerges as a central command post for immune intelligence, mood regulation, and systemic inflammation, driven by microbial diversity and intestinal barrier integrity.

Part 4 addresses hormonal harmony as a symphony disrupted by stress, diet, and environmental inputs. It unpacks the insulin-cortisol-thyroid triad and offers natural recalibration strategies. Part 5 delves into metabolism beyond calories—exploring mitochondrial adaptability and the keys to metabolic flexibility. Part 6 reveals chronic inflammation as the unifying pathology in most modern disease, and how anti-inflammatory lifestyles downregulate this biochemical fire at its root.

Part 7 challenges detox myths, advocating evidence-based support of the liver, kidneys, and lymphatics through fasting, phytochemicals, and daily rituals. Part 8 reframes stress as a nervous system dysfunction and shows how to neurologically shift from survival mode to healing mode.

Part 9 redefines nutrition as information, not just fuel—emphasizing nutrient density, micronutrient synergy, and the science of meal timing. Part 10 recasts movement as medicine, highlighting the regenerative effects of brief, intelligent physical inputs throughout the day.

Part 11 presents belief and mindset as biological modifiers, revealing how placebos, ritual, and expectation directly modulate pain, immunity, and recovery via brain-immune circuits. Finally, Part 12 unpacks the frontier of longevity science—autophagy, senescence, fasting, and cellular rejuvenation—culminating in a unified model for extending healthspan.

This is not just a health manual—it’s a manifesto for reclaiming agency, decoding the body’s intelligence, and transforming how we heal.

Part 1: The Root Cause Revolution & Hidden Imbalances

Stop treating symptoms. Start decoding the body’s hidden signals.

1.1 Why Symptoms Lie: Uncovering the Hidden Imbalances

The modern medical system tends to treat symptoms as the problem. Yet symptoms—fatigue, pain, mood disturbances, digestive upset, stubborn weight gain—are rarely the true disease. They are the body’s alarm signals: downstream responses to deeper dysfunctions. To truly heal, it is imperative to shift focus upstream: to detect and correct the hidden imbalances that lie behind symptoms.

Recent work in functional medicine underscores the non‑deterministic interaction among genetics, environment, lifestyle, behavior, and epigenome. As Bland (2022) emphasizes in Functional Medicine Past, Present, and Future, altered physiologic function is often reversible when upstream causes are addressed, rather than simply waiting for disease criteria to be met.

Similarly, research into the microbiota‑gut‑immune‑brain axis reveals how systemic immune signaling, microbial metabolites, barrier integrity, and neuroinflammation interact to generate mood disorders, cognitive dysfunction, and more—often long before overt disease is diagnosed. These interactions are hidden, but potent.

Below are core categories of hidden imbalances, why they are often missed, and the consequences of ignoring them.

Major Hidden Imbalances

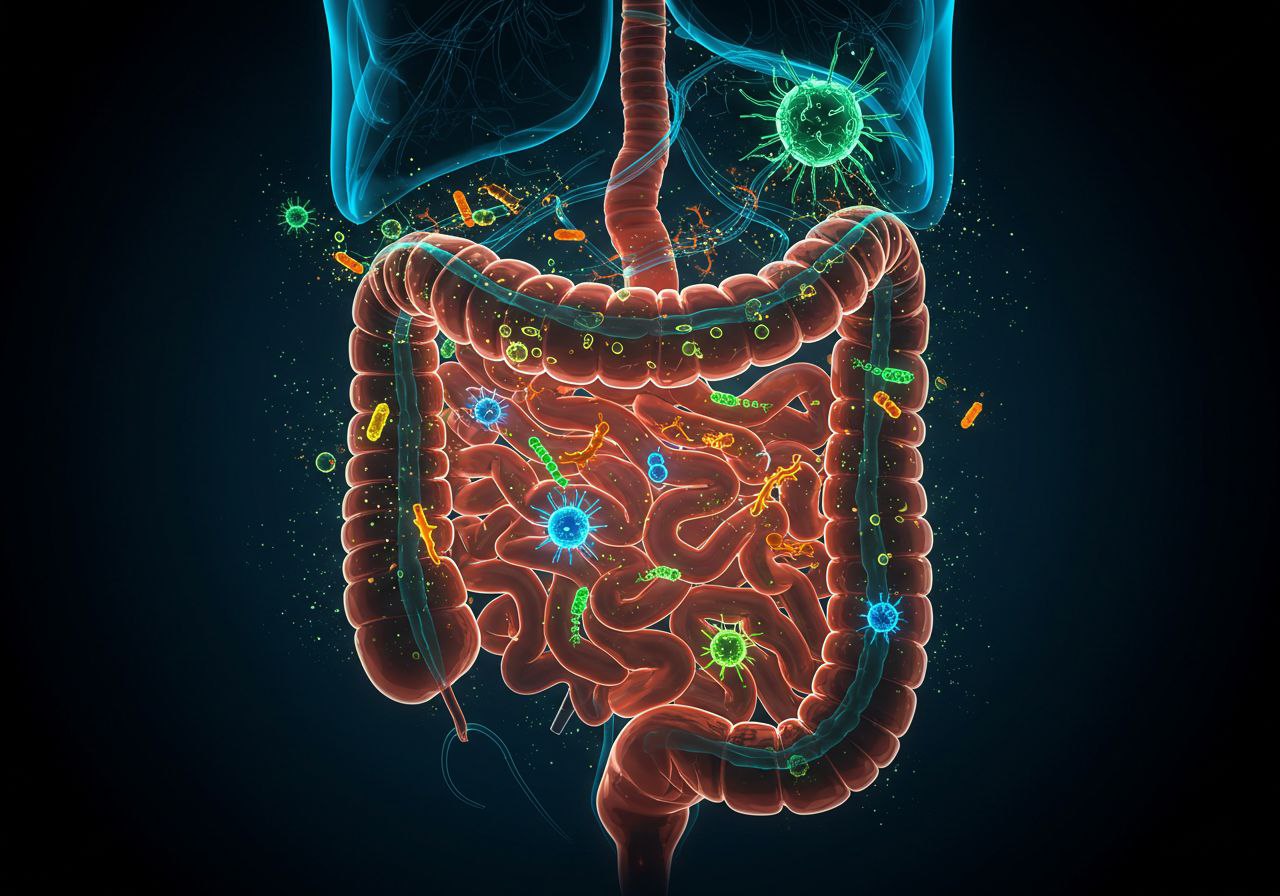

- Microbiome and Gut Barrier Dysfunction

The gut microbiota is now known to do far more than digest food: it plays a regulatory role over immune balance, neural signaling, metabolic health, and brain function. Disruption of the microbiome composition (dysbiosis), increases in gut permeability (“leaky gut”), and reduced production of beneficial microbial metabolites (like short‑chain fatty acids, SCFAs) can precipitate systemic inflammation and modulate both innate and adaptive immunity. These changes are implicated in depression, anxiety, neurodevelopmental disorders, and even neurodegenerative disease. - Immune / Inflammatory Dysregulation

Persistent low‑grade inflammation, elevated cytokine signaling, a misregulated immune response (innate and adaptive), and immune processes in barrier tissues (gut, lung, skin) often produce no overt signs until later stages. The gut‑immune‑brain axis review by O’Riordan et al. (2025) notes immune dysregulation as a core mediator between microbiota changes and brain dysfunctions. - Epigenetic & Genetic Expression Drift

Though our genes matter, the way genes express themselves is highly responsive to environment, diet, stress, sleep, toxins, and behavior. Bland (2022) explains how functional medicine sees health as a dynamic interplay among epigenome, lifestyle, and external exposures; aging epigenome changes are not necessarily irreversible. - Metabolic and Hormonal Imbalances

Early shifts in insulin sensitivity, thyroid function drift, cortisol dysregulation (from chronic stress), sex hormone changes, and mitochondrial inefficiencies often lie beneath fatigue, weight gain, mood issues—even before lab values formally cross into “abnormal.” These are often overlooked because they are subtle and slow to manifest. - Lifestyle & Environmental Exposures

Poor diet, lack of sleep, chronic stress, inadequate movement, overexposure to pollutants, antibiotic overuse, and psychosocial stress (trauma, social isolation, etc.) contribute to upstream dysfunctions. These often set the stage years or decades before illness emerges.

Why Symptoms Tie Us in Knots

- Compensatory mechanisms: The body often adapts to imbalance for a long time. For example, if insulin resistance begins, the pancreas may increase insulin production, masking symptoms until compensation fails.

- Threshold effects in diagnostics: Many lab or imaging thresholds are set to detect “disease” after damage has accumulated. Early drift or dysfunction below disease threshold is often ignored.

- Fragmented specialization: Conventional medicine often treats organs or systems in isolation. A specialist might treat the thyroid, another the gut, another the brain—without seeing the systemic interconnections.

- Patient expectations and system incentives: Many people expect immediate symptom relief. Doctors are often pressured to relieve symptoms first, especially in acute settings. Preventive or upstream approaches may seem less urgent or less reimbursable.

The Costs of Ignoring Hidden Imbalances

- Progression from mild dysfunction to full‑blown disease (e.g. pre‑diabetes → type 2 diabetes; subclinical hypothyroidism → overt disease).

- Chronic disease comorbidity: once one system is disturbed, others often follow (metabolic to cardiovascular, immune to neurological, etc.).

- Reduced quality of life, increased healthcare costs, side effects from symptom‑suppressing therapies.

- Loss of recovery window: early dysfunction is often more reversible; later disease is more difficult, riskier, and slower to treat.

1.2 Conventional Medicine vs. Functional Health

Juxtaposing these two paradigms helps clarify why many modern illnesses resist conventional treatment, and why functional health offers a more promising route for root‑cause recovery.

| Feature | Conventional Medicine | Functional Health / Functional Medicine |

| View of disease | Disease = diagnosis based on thresholds (lab values, imaging, symptom clusters). Once disease named, treat it. | Dysfunction first; disease as endpoint. Seek to detect and correct dysfunction before thresholds are crossed. |

| Treatment focus | Usually symptoms: pills, surgery, standardized pharmacotherapy. | Multimodal: diet, lifestyle, environment, nutrition, stress management; personalized to individual history and exposures. |

| Diagnostics | Standard labs, imaging, guideline‑based measures; often reactive. | More sensitive, broad spectrum testing: microbiome, epigenetics, immune profiling, exposure history, etc. Proactive detection of dysfunction. |

| Prevention vs acute care | Emphasis on acute care and managing disease after diagnosis. Some preventive work, but often secondary. | Heavy emphasis on prevention, early intervention, restoring resilience and homeostasis to avoid disease onset. |

| Patient role | More passive: follow prescriptions; limited behavioral prescription outside general advice. | Active partnership: behaviors, environment, mindset central; patient engagement and education vital. |

| Time horizon | Generally short‑term or disease stage‑by‑stage management. | Long‑term healing and prevention; often slower but with potential for more complete restoration. |

What Conventional Medicine Does Well

- Handling acute, life‑threatening, or surgical emergencies (trauma, infections, acute heart attacks, etc.).

- Rigorous, well‑validated treatments for many diseases once they are established.

- Strong regulatory systems, extensive research on drugs and procedures, biomarker‑based trials.

Where It Falls Short, Especially for Chronic Disease

- Under‑emphasis on root causes: for example, high‑sugar diets, chronic sleep loss, environmental toxins, subclinical immune activation.

- Fragmented care: treating parts rather than considering the system as a whole.

- Often reactive; symptoms drive visits rather than proactive maintenance of health.

- Limited scalability of lifestyle and preventive interventions in many healthcare systems (insurance, time, training).

What Functional Health Adds (Evidence)

Functional health (or functional medicine) is not a new fad, but a response to clear gaps. Bland (2022) reviews how functional medicine has evolved and its potential: the model sees function (not just disease), believes in flexibility of the epigenome, and in personalized intervention.

From the microbiota side, the review by O’Riordan et al. (2025) describes how crossing signals from gut microbiota to immune system to brain underlie many psychiatric, developmental, and neurological disorders—and how precision interventions (diet, probiotics, modulo immunity) could modulate these.

Functional Health in Practice: Core Principles

- Holism: Viewing the person as an integrated whole: digestive, hormonal, immune, mental, environmental.

- Personalization: Because hidden imbalances differ per individual, one‑size‑fits‑all rarely works. What triggers disease in one may be tolerated in another.

- Dynamic timelines: Health is not static; dysfunctions may build gradually over years. Mapping personal and family history, exposures, lifestyle over time is important.

- Multilayered intervention: Intervene via multiple levers: nutrition, sleep, detox/environment, stress, movement.

- Restore resilience and function before disease: the aim is to shift upstream, not only treat downstream symptoms.

1.3 How to Spot the “First Domino” that Triggers Disease

Identifying the first domino—the earliest cause in the causal chain—is both an art and science. It requires a systems perspective, a deep history, and the right diagnostics.

In this expanded version, I include both methodological frameworks and real‑world case examples.

Methodological Frameworks for First‑Domino Discovery

To reliably find the root trigger, clinicians and individuals can use a structured approach:

- Life‑Course Functional Timeline / Health Map

- Begin from birth (or even prenatal if data available): note early infections, antibiotic use, stress, major life events, diet transitions.

- Track onset of symptoms with timing relative to exposures (toxins, stressors, diet changes, hormonal shifts, environmental moves).

- Include psychosocial and emotional history, family history, and environmental exposure (chemical, microbial, occupational).

- Mark periods of compensation: when symptoms first appeared, when they fluctuated, when they worsened.

- Systemic Functional Matrix

- Map across core physiological systems: gut / microbiome; immune and inflammatory; endocrine / hormones; mitochondrial / energy metabolism; detoxification / biotransformation; structural (musculoskeletal) and nervous system.

- For each system, mark strengths and weaknesses, symptoms, lab indicators, lifestyle exposures that might affect it.

- Look for patterns of interaction: gut‑immune, immune‑brain, endocrine‑metabolic.

- Targeted diagnostics for dysfunction, not just disease

- Use functional laboratory tests (microbiome sequencing, stool markers, immune/inflammatory markers, metabolic panels, organic acids).

- Assess hormone panels including adrenal, thyroid, sex hormones, along with feedback markers (antibodies, binding proteins).

- Assess detoxification capacity, exposure loads (if indicated), and mitochondrial performance.

- Utilize tools like epigenetic clocks, where validated, to estimate biological age drift.

- Pattern Recognition / Cross‑System Clues

- Notice when multiple systems show early dysfunction concurrently (e.g., mild gut symptoms + mood changes + poor sleep + low energy).

- Often the first domino shows up subtly in more than one domain before full disease emerges.

- Use deductive logic: e.g., if gut permeability is present, immune system will be chronically stimulated, which may then drive hormonal dysregulation or mental health symptoms.

- Intervention as Diagnostic Tool

- Small, safe interventions (diet changes, probiotics, sleep improvement, stress reduction) can serve as “probes” to see whether correcting one domain improves others. If sleep improvement reduces inflammation, that suggests sleep might be an early domino.

- Ongoing Monitoring and Feedback

- Reassess after interventions: labs, symptoms, energy, mood.

- Be willing to iterate: if one hypothesis doesn’t resolve dysfunction, move to the next upstream factor.

Case Study A: Early Dysbiosis as First Domino → Mood and Sleep Disturbances

Patient Profile: 29‑year‑old female with chronic fatigue, insomnia, mild anxiety, and gastrointestinal bloating. Labs mostly “normal” except mild low sleep efficiency, elevated gut permeability markers, low SCFA producing bacterial populations.

Timeline & History Clues:

- Childhood antibiotics for ear infections through age 10.

- Gluten introduced late; lactose intolerance symptoms noticed in teenage years.

- Transitioned to college life, with stress, irregular sleep, fast food diet.

Functional Matrix Findings:

- Gut: dysbiosis, low microbial diversity, signs of leaky gut.

- Immune: elevated cytokine markers, occasional allergies.

- Hormones: mild cortisol drift (delayed morning peak).

- Sleep: delayed sleep onset, fragmented deep sleep fractions.

First Domino Hypothesis: Gut dysbiosis with loss of SCFA producers → increased gut permeability → immune activation → low‑grade inflammation interfering with neurotransmitter balance and sleep architecture.

Interventions:

- Dietary reset: elimination of refined sugars, refined grains, addition of fermentable fiber and prebiotics.

- Probiotic and microbiome support targeted to increase butyrate producers.

- Sleep rituals improved: fixed sleep schedule, removal of electronics before bed, light therapy (morning), dark environment at night.

- Stress reduction: mindfulness, breathwork.

Outcomes:

- Over 3 months, sleep onset latency improved, deep sleep percentage increased (measured via home sleep tracking), fatigue and anxiety reduced. Gastrointestinal symptoms abated.

This case illustrates how gut imbalance served as the initiating domino; once corrected, multiple downstream symptoms improved.

Case Study B: Hormone Drift and Sleep Loss → Metabolic Breakdown

Patient Profile: 45‑year‑old male with increasing weight (particularly around abdomen), rising fasting glucose, mood swing, impaired concentration, and poor sleep quality though sleeping 7‑8 hours.

History & Timeline:

- Long hours at work, high stress for many years.

- Occasional shift work.

- Diet rich in processed carbohydrates, low in fiber.

- Travel across time zones.

Functional Matrix:

- Endocrine: rising insulin resistance (fasting glucose borderline), lowered testosterone, elevated evening cortisol.

- Sleep: signs of circadian mis‑alignment despite duration preserved; poor sleep quality (light sleep, few deep sleep epochs).

- Immune/Inflammation: elevated high‑sensitivity CRP, IL‑6.

- Gut: somewhat reduced diversity, occasional SIBO symptoms.

First Domino Hypothesis: Sleep quality / circadian rhythm disruption (though hours sufficient) = first domino → leading to hormonal drift (cortisol, insulin) → metabolic dysfunction, inflammation, mood disturbances.

Interventions:

- Reinforced circadian discipline: fixed wake time, morning light exposure, limiting evening light, avoiding late meals.

- Diet adjustments: more protein, lower glycemic load, inclusion of fiber.

- Exercise timed earlier in day.

- Support of hormonal axis: sleep hygiene, adaptogens, possibly measurement of testosterone and supplementation only if needed.

Outcomes: After 4–6 months, improved insulin sensitivity, reduction in abdominal fat, mood and cognition better, energy levels higher. Sleep quality improved (more deep sleep, less waking), less nighttime cortisol measured.

How the References Support These Insights

- Bland (2022) provides foundational justification for viewing health through functional medicine lenses: that many changes in physiology are not locked in by genetics, that the epigenome is responsive, and that root‑cause interventions can reverse early dysfunction.

- O’Riordan et al. (2025) detail mechanisms of the gut‑microbiota‑immune‑brain axis; how immune signaling mediates brain outcomes, and how microbiota changes can precede psychiatric signs. This supports the idea that gut dysbiosis and immune dysregulation are among the most potent “first dominos” in many people.

- Ancillary data from related reviews (e.g. in Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis in Psychiatry, Wang et al., 2024) show that brain, mood, behavior changes often correlate with gut microbiota changes, often mediated by immune and HPA‑axis mechanisms.

The Practitioner’s Lens: Using First Principles to Reverse Complexity

One of the central advantages of the “first domino” model is that it restores clarity amidst clinical complexity. Where conventional medicine may see a cluster of overlapping, escalating diagnoses—e.g. chronic fatigue, anxiety, irritable bowel syndrome, hypothyroidism, and prediabetes—a functional lens views these as expressions of one or two early system imbalances left uncorrected. The practitioner’s task is to reduce this complexity by following the physiology upstream.

This begins with asking: What went wrong first? When did the body begin to drift out of alignment—and what triggered it?

The answer is often found not in one variable, but in the convergence of several small breakdowns: a loss of gut diversity, a few months of poor sleep, a subtle hormonal shift, a change in diet, a prolonged stressor. Over time, this becomes a tipping point.

Integrated Case Mapping: A Full-System View

Let’s synthesize a broader case to illustrate how multiple downstream diagnoses can often be traced back to a common initiating dysfunction.

Composite Case Study: Maria, Age 39

Presenting complaints: Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, anxiety, constipation, brain fog, hair loss, fatigue, weight gain.

Medications: Levothyroxine, sertraline, occasional ibuprofen for joint aches.

Functional History & Timeline:

- Age 5–10: Recurrent tonsillitis; antibiotics 3x/year

- Age 14: Mood changes around menses

- Age 19: Started oral contraceptives, experienced constipation and eczema flare-ups

- Age 25: Car accident, experienced trauma and post-traumatic stress symptoms

- Age 30: Diagnosed with “subclinical hypothyroidism”

- Age 35: Diagnosed with Hashimoto’s; TPO antibodies high, fatigue worsened, gained 20 lbs in 2 years

- Age 36–39: Developed constipation, anxiety, irregular sleep; sertraline prescribed

Functional Mapping:

- Gut: Dysbiosis suspected (constipation, eczema history, antibiotic exposure)

- Immune: Hashimoto’s indicates loss of self-tolerance; systemic inflammation likely

- Hormonal: HPA axis dysfunction, suboptimal adrenal support, downstream thyroid effects

- Metabolic: Mild insulin resistance; weight gain, fatigue

- Neurological: Anxiety, brain fog suggest neuroimmune disruption

First Domino Identified: Childhood antibiotic exposure → gut dysbiosis → impaired barrier function and mucosal immunity → systemic immune drift → loss of self-tolerance → thyroid autoimmunity → hormonal dysregulation → mood and energy sequelae.

Functional Interventions:

- 8-week gut repair protocol (including antimicrobials, prebiotics, mucosal healing agents)

- Elimination diet with slow reintroduction

- Mind-body stress reduction training (yoga, breathwork)

- Adaptogenic herbs + micronutrient support (selenium, zinc, B12)

- Circadian rhythm reset (early light, early dinner, sleep hygiene)

Outcome: Over 6 months, TPO antibodies halved, mood stabilized, digestion normalized, hair regrowth noticed, energy improved, 12 lb weight loss without calorie counting. Levothyroxine dose reduced under supervision.

Practical Application: Self-Inquiry and Personal Timeline

Even for non-practitioners, creating a personal health timeline can be a transformative step in identifying the first domino.

Steps to Create Your Personal Root Cause Map:

- List all significant health events: illnesses, medications, traumas, infections, diet/lifestyle shifts.

- Mark when each symptom began: and what was happening around that time—life changes, stress, food/environment exposures.

- Assess systems: gut, sleep, mood, energy, hormones—what was “off” earliest?

- Identify patterns: Do digestive symptoms precede fatigue? Does poor sleep correlate with anxiety spikes? Are infections triggering flares?

- Create a chronological flow: a “domino map” from early imbalance to current complaints.

Once that map is drawn, potential first dominos often reveal themselves—not as isolated events, but as initiators of dysfunction across systems.

The Body as an Ecosystem: Domino Effects Are Systemic

Functional medicine demands we view the body not as compartments, but as a living system of interlocking feedback loops. The gut affects the brain via the vagus nerve and cytokines. The adrenals influence thyroid hormone conversion. Insulin resistance changes neurotransmitter dynamics. Sleep deprivation raises inflammatory set points.

Each of these systems influences the others. But the domino that tips the system often comes from the weakest link in a person’s physiology or environment—where resilience is already stretched thin.

The revolution in root-cause thinking doesn’t reject conventional medicine—it reframes it. By integrating systems biology, lived experience, and upstream diagnostics, it offers a more coherent way to understand chronic illness.

Key Takeaways:

- Symptoms are signals, not explanations. Suppressing them without tracing them upstream risks chronic relapse and medication cascades.

- Hidden imbalances precede visible disease. Gut health, immune drift, hormonal dysregulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and toxic load must be addressed before they become permanent pathology.

- Conventional and functional medicine differ not in rigor, but in lens. One treats labels; the other treats patterns. One focuses downstream; the other upstream.

- The first domino is individual. For some it’s gut-related, for others stress, for others an inflammatory insult or toxin. But it can always be traced with time, pattern recognition, and the right tools.

- Healing requires systems thinking and personalization. A one-size-fits-all approach cannot reverse a body whose dysfunctions were individually acquired.

Conclusion: From Diagnosis to Discovery

The Root Cause Revolution is not merely a philosophical stance—it is a clinical, biological, and personal imperative. In an age of exploding chronic disease, it offers something that symptom-based medicine often cannot: hope through understanding.

The message is simple yet radical: Your body is not broken—it is out of balance. And once the first domino is found, everything downstream can begin to reset.

Part 2: Sleep as the Master Switch

Reset your hormones, energy, and brain power—starting with sleep.

Sleep is the foundational healer. It’s the stage upon which our hormones dance, our metabolism is regulated, the immune system recalibrated, and even new hormones are discovered. In this section we explore how sleep controls hormonal cascades, why deep sleep matters more than just accumulating hours, and the evening rituals and circadian resets that can turn your sleep into a master switch of health.

2.1 The Hormonal Cascade Controlled by Sleep

Sleep isn’t simply rest—it’s a highly orchestrated sequence of states (NREM, REM) that trigger, suppress, and regulate hormones in ways that affect metabolic health, appetite, repair, mood, and long‑term disease risk.

Key Hormonal Players

- Growth Hormone (GH): Released predominantly during slow‑wave (deep) non‑rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. It supports tissue repair, muscle growth, metabolism regulation. Poor deep sleep blunts GH secretion.

- Cortisol: Tied to the HPA (hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal) axis. Normally, cortisol dips during deep sleep; disruptions in sleep (fragmented, insufficient, or altered architecture) can delay the drop, prolong elevated cortisol, or flatten its circadian rhythm. Elevated nighttime or early morning cortisol is linked to impaired glucose tolerance, weight gain, and stress.

- TSH / Thyroid hormones (T3/T4): Sleep modulates TSH secretion; NREM sleep tends to suppress TSH, meaning that sleep disturbances may lead to elevated TSH and downstream thyroid axis effects.

- Sex hormones (Testosterone, etc.): REM sleep appears particularly relevant for the timing and rhythm of testosterone release; disruption in REM latency or duration can affect male reproductive/hormonal health.

- Appetite and metabolic regulatory hormones: Leptin, ghrelin, and more recently identified molecules like Raptin mediate hunger, satiety, gastric function in response to sleep states.

Recent Evidence

Two major recent studies illuminate these hormonal cascades.

- Sleep disorders and hormonal regulation (Jiao et al., 2025) → This review (Biomed Central) shows how disrupted architecture (altered ratios of NREM vs REM, poor quality of deep sleep) impacts GH, cortisol, TSH, testosterone, leptin, etc. Particularly, NREM sleep helps suppress TSH, facilitate GH release, reduce cortisol thereby improving glucose metabolism; REM sleep governs other variables like testosterone rhythm and influences the sympathetic nervous system, which has metabolic consequences.

- Discovery of Raptin (Xie et al., 2025) → A newly‑identified sleep‑induced hypothalamic hormone (cleaved from RCN2) that is released during sleep, peaking in healthy sleep but blunted with sleep deficiency. Raptin binds to GRM3 in hypothalamus + stomach, inhibiting appetite and gastric emptying. Sleep deficiency → reduced Raptin → increased appetite and obesity risk. This mechanistic discovery connects sleep directly to metabolic control and body weight regulation.

- Neuroendocrine circuit for sleep‑dependent GH release (Ding et al., 2025) → Research (Cell, etc.) shows both REM and NREM contribute to GH release, and the patterns of their activation are regulated by sleep–wake circuitry. (This supports the idea that it’s not enough simply to sleep many hours; the architecture and timing of sleep states matter.)

- Corticotropin‑releasing hormone (CRH) and NREM consolidation (Cumpana et al., 2025) → This article reports how CRH modulates NREM sleep consolidation via the thalamic reticular nucleus; stress signals even within sleep can fragment deep/NREM sleep, reducing its restorative benefit. Thus hormonal signaling (here CRH) both influences and is influenced by sleep architecture.

Why Sleep Structure Matters More than Just Sleep Duration

Many people assume more hours = better health. While duration is important, recent data make clear that deep sleep / slow wave sleep (NREM stage 3) and balanced REM are more predictive of hormonal balance and metabolic health.

- Deep sleep is the point at which GH surges, protein synthesis and repair, immune restoration, metabolic “resetting” occur. If deep sleep is truncated or fragmented, even if total sleep time is “adequate,” these processes suffer. (From Jiao et al. 2025; also field observations in sleep medicine.)

- REM sleep also serves important roles (emotional processing, some metabolic regulation, sex hormone timing). But too much REM, or delayed REM onset, or disrupted REM (fragmented REM) can correlate with metabolic derangement (e.g. via sympathetic system activation, insulin/cortisol pathology). Jiao et al. note that high proportion of REM can reduce leptin levels, which can increase appetite/fat storage.

- Stress hormones such as CRH or cortisol interfere with sleep architecture (especially deep sleep / NREM consolidation). Elevated CRH can fragment NREM, reducing delta wave power, reducing restorative effects. The CRH‑TRN (thalamic reticular nucleus) work shows how stress peptides disrupt deep/NREM patterning.

2.2 Why Deep Sleep Is More Powerful Than More Hours

Let’s drill more deeply (pun intended) into why slow wave sleep (deep NREM) is a mathematical and physiological leverage point for health.

Deep Sleep: What Happens

During deep sleep:

- Delta waves dominate: large, slow brain waves characteristic of deep NREM.

- Synaptic downscaling occurs: brain pruning of unnecessary connections, strengthening of useful ones, clearing of metabolic by‑products via glymphatic flow. This helps memory consolidation, emotional processing, neuroprotection.

- GH surge: The biggest pulses of growth hormone often occur in deep sleep. This supports tissue repair, muscle regeneration, and has metabolic effects (lipolysis, improved insulin sensitivity).

- Immune modulation: Cytokine regulation, leukocyte repair, vaccine response, inflammation reduction are all closely tied to deep sleep.

Deep Sleep vs. Long Sleep: The Risks of Poor Architecture

Several patterns show harm even when total hours seem sufficient but sleep is shallow / fragmented:

- People with long time in bed but many awakenings, poor sleep efficiency, or light sleep dominance (little stage 3) tend to have elevated markers of inflammation, impaired glucose tolerance, mood disturbances.

- Chronic sleep disorders—sleep apnea, insomnia, circadian misalignment—often reduce deep sleep disproportionately. These disorders are strongly tied to metabolic disease beyond just short sleep.

From Jiao et al.: Poor deep sleep → blunted GH release, elevated cortisol, disrupted TSH suppression, insulin resistance, appetite dysregulation.

From Raptin work: Sleep deficiency not only reduces overall hours but specifically disrupts the timing of Raptin release, which requires proper sleep architecture. The hormone peaks during sleep when circuits from suprachiasmatic nucleus → PVN are functioning; disrupted sleep blunts that peak. Thus metabolic regulation worsens not just because of “less sleep”, but “wrong sleep.”

Also, CRH‑TRN research: stress‑related peptides (CRH) fragment NREM sleep, reduce sleep spindle and delta power, fragment deep sleep, reducing its restorative power. Again, more hours won’t compensate if architecture is bad.

2.3 Evening Rituals That Reset Circadian Rhythm

Knowing how powerful sleep architecture is, the actionable question becomes: How can you set your evening & circadian environment to optimize deep sleep, REM, hormonal harmony?

Here are practices, supported by recent research, to help reset and maintain your circadian rhythm, improve sleep architecture, and amplify health benefits.

Evening Rituals & Environmental Strategies

- Consistent Sleep‑Wake Schedule

- Going to bed and waking at the same time every day strengthens circadian entrainment. The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) which acts as your master clock, expects consistency. Irregular schedules confuse it, reduce amplitude of hormonal cycles (cortisol, melatonin, GH, etc.).

- Raptin work shows that the SCN → PVN circuit is central in timing hormone release; irregular sleep undermines that signal. Nature

- Light Management

- Morning exposure to bright natural light helps (or light boxes) to set the “day” signal.

- Evening light should be dim, low blue‑light (e.g. from screens), ideally warmer in color. Use of blue‑light blockers/screens off before 1‑2 hours before bedtime.

- The Begemann et al. article, Endocrine regulation of circadian rhythms (2025), emphasizes the feedback loops: melatonin, cortisol, body temperature all serve as outputs and inputs to the clock. Light exposure influences melatonin suppression etc. (evening exposure delays melatonin, delays sleep onset).

- Evening Meal Timing

- Avoid heavy or late meals close to bedtime; metabolic processing (insulin, digestion) can interfere with deep sleep.

- In animal and human work (including Raptin), gastric emptying is part of the pathway by which sleep signals reduce appetite; interfering with gastric phase via late eating might blunt these signals.

- Pre‑Sleep Wind‑Down Rituals

- Rituals send your nervous system cues that sleep is approaching: reading, warm bath, light stretching, meditation, breathwork.

- Reducing cognitive/emotional arousal is important: worry, screen‑based stimulation, bright or garish light, loud noise should be curtailed.

- Managing Stress / Emotional Load

- Because CRH and other stress hormones disrupt sleep architecture (see the study on CRH modulation of NREM via thalamic reticular nucleus). Practices like mindfulness, journaling, emotional processing in the evening matter. These reduce CRH activation, allow deeper NREM consolidation.

- Temperature and Environment

- The bedroom should be cool; slight drop in core body temperature facilitates onset of deep sleep.

- Darkness (low ambient light), quiet, minimal disturbances. Use of blackout curtains, reduce ambient noise.

- Avoiding/Subduing Disruptors

- Caffeine, nicotine, alcohol later in day degrade sleep architecture (fragment deep sleep, affect REM).

- Digital devices, bright screens, notifications can activate sympathetic nervous system.

- Shift work, irregular shifts, jet lag: when unavoidable, use light exposure, melatonin (if under healthcare guidance) to help reset.

Circadian Reset Strategies

- Anchor points: Use light and meals as anchor points. For example, morning light + breakfast at consistent time; evening light reduction + dinner ideally several hours before sleep.

- Melatonin support (natural / timed): In some cases, very low doses to help onset can be used, but in general better to allow natural melatonin production (supported by darkness, less blue light).

- Exposure to natural light outdoors: Even brief exposure in morning helps entrain the clock.

- Avoid social jet lag: Keep weekend schedules close to week schedules to avoid shifting clock; large shifts in wake/sleep times constantly confuse hormones.

Case Studies

To bring these principles into life, here are two realistic case studies demonstrating how applying these sleep‑hormone principles can reset the system.

Case Study 1: Sleep Depth Restoration in a Woman with Metabolic Drift

Background:

- 38‑year‑old woman (call her “Lena”) with increasing abdominal weight, mild fasting hyperglycemia, fatigue, occasional mood lability. Sleeps ~7.5–8 hours/night but often wakes several times, reports light sleep dominantly; little sense of rest upon waking.

Assessment / Observations:

- Sleep tracking: shows low percentage of NREM stage 3 (deep sleep), fragmented awakenings, delayed REM onset.

- Labs: mildly elevated cortisol at night, elevated TSH (upper normal), insulin resistance beginning (HOMA‑IR up), elevated fasting glucose ~110 mg/dL. Leptin/ghrelin somewhat dysregulated.

First Interventions:

- Tighten bed/wake schedule: fixed wake time 6:30 AM, bedtime 10 PM.

- Light exposure: bright natural light first thing; avoid screens from 9 PM; install dim amber lighting.

- Pre‑sleep ritual: warm bath, stretching, journaling to offload stress.

- Evening meal before 7:30 PM, light snack if needed; no heavy food after.

- Stress reduction: breathing exercises or meditation nightly; occasional yoga.

Follow‑Up (3 months):

- Deep sleep percentage increased (tracked via a home sleep device) by 30%; fewer awakenings.

- Morning cortisol more appropriately low; evening cortisol lower.

- Fasting glucose improved; insulin sensitivity increased.

- Appetite more regulated (fewer late‑night cravings).

- Weight loss of ~8 lbs without calorie counting; mood improved.

Case Study 2: Raptin Pathway & Sleep Deprivation in a Man with Obesity

Background:

- “Mark”, age 45, BMI 32, long history of short sleep (5‑6 hours), shift work, frequent late‑night eating. Complaints: constant hunger, weight gain despite caloric restriction attempts, lethargy.

Assessment / Observations:

- Sleep deprived; poor sleep architecture.

- Appetite high; cravings at night; disrupted eating schedule. Possibly lowered Raptin (per hypothesized based on study).

Interventions:

- Increase nightly sleep duration to 7.5 hours, focusing on earlier bedtime.

- Eliminate late‑night snacks; restrict eating window (e.g. no calories after 7 PM).

- Avoid bright light and screens after 9 PM.

- Morning exposure to light.

- Added walking/exercise earlier in day to help entrain metabolic/hormonal rhythm.

Follow‑Up (4‑6 months):

- Cravings reduced; hunger more silenced overnight; evening appetite reduced.

- Weight began to plateau, then slowly drop.

- Sleep became deeper (measured via subjective restfulness + devices).

- Mark reported food being less tempting at night; smaller portions naturally.

This outcome aligns with the mechanistic model: improved sleep → improved Raptin release → suppression of appetite and gastric emptying → better metabolic control.

Practical Guide: Putting Sleep to Work as Your Master Switch

Here is a daily / weekly plan you can follow (or apply as a guide if you’re a practitioner working with clients) to reset sleep, hormonal cascades, and maximize health gains.

| Time Period | Action | Purpose / Effect |

| Morning | Wake at consistent time; get bright natural light (ideally within 30 minutes) | Resets SCN; reinforces circadian rhythm; helps normalize cortisol rise |

| Eat breakfast within 1 hour of waking | Supports metabolic hormone rhythm; anchors clock | |

| Daytime | Minimize naps (if disruptive); avoid heavy caffeine after early afternoon | Enhances sleep pressure; avoids interference with melatonin onset |

| Physical activity/exercise, ideally in morning / early day | Boosts sleep architecture, improves metabolic health | |

| Afternoon | Light exposure outdoors; avoid long sedentary periods | Strengthens circadian entrainment; reduces afternoon energy dips |

| Evening (3‑4 hours before bed) | Eat dinner earlier; make it balanced; limit heavy protein/fat close to bed | Improves digestion; avoids insulin/glucose interference with sleep |

| Dimming lights; reduce screen use; blue‑light filters | Allows melatonin onset; reduces circadian delay | |

| Pre‑sleep ritual: baths, reading, journaling, stretching, breathwork | Lowers arousal; helps shift into parasympathetic mode | |

| Bedtime | Fixed bedtime; dark, cool, quiet environment; comfortable bedding | Supports deep sleep; reduces awakenings |

| Night | Minimize disruptions (noise, light); manage sleep disorder if present (apnea, leg movements, etc.) | Ensures sleep architecture integrity |

| Weekly Habits | Review sleep logs or device metrics; note deep sleep %, awakenings, feeling rested | Adjust bedtime, rituals, environment accordingly |

| Reflect on stressors; practice stress buffer (yoga, meditation, therapy) | Reduce CRH/hormonal disturbance |

Implications for Health

Proper sleep has cascading impact across many health domains:

- Metabolic disease prevention: Better GH, insulin sensitivity, appetite regulation decreases risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes.

- Cardiovascular health: Sleep improvement helps normalize blood pressure, reduce sympathetic overactivation.

- Endocrine balance: Thyroid, sex hormones, adrenal health improve when sleep architecture is preserved.

- Mental health: Mood, stress resilience, cognitive clarity are all highly sensitive to sleep structure.

- Longevity & repair: Cellular repair, immune function, DNA repair are maximized during deep sleep.

Summary & Integration

- Sleep is not a passive process—it is deeply hormonal and regulatory.

- Deep NREM sleep (slow‑wave), appropriate REM, intact sleep architecture matter more than just raw sleep duration.

- New discoveries like Raptin show molecular pathways linking sleep states directly to appetite/metabolism.

- Elevated stress hormones, sleep fragmentation, delayed light suppression, irregular schedules all interfere with sleep’s regulatory function.

- Evening rituals and circadian reset strategies have robust evidence in setting the stage for optimal sleep architecture.

Part 3: Gut Health: The Command Center

Your gut runs the show—mood, metabolism, and immunity all begin here.

The gut is much more than a food processor. It’s a command center. It regulates immunity, mood, metabolism, and even long‑term disease risk through complex interactions of microbes, intestinal barrier integrity, immune signaling, and neuronal feedback. In this section we explore:

- 3.1 The microbiome’s role in mood, weight, immunity

- 3.2 Foods that secretly damage gut balance

- 3.3 The three daily habits to restore a thriving gut

We’ll use recent research—including Park & Han (2025), Halabitska et al. (2024), Medina‑Rodríguez et al. (2024), etc.—to anchor theory, then move to illustrative cases and then practical interventions.

3.1 The Microbiome’s Role in Mood, Weight, and Immunity

Key Concepts & Mechanisms

Recent reviews emphasize that gut microbiota (the community of microbes in the digestive tract) has major influence on:

- Immune regulation and systemic inflammation

- Gut barrier integrity (“leaky gut”)

- Metabolic regulation: weight, fat storage, obesity, insulin sensitivity

- Mood, behavior, psychiatric disorders

These are mediated via:

- Microbial metabolites (short‑chain fatty acids (SCFAs), tryptophan derivatives, secondary bile acids)

- Immune cell modulation (e.g. Th17, Treg balance)

- Vagus nerve and enteric nervous system communication

- Signaling via HPA axis, hormonal feedback loops

Recent Evidence

Park, J. C., & Han, K. (2025). “Decoding the gut‑immune‑brain axis in health and disease.” Cellular & Molecular Immunology.

This review (2025) lays out a mechanistic framework: how gut microbiota influences both innate and adaptive immune systems; how microbial metabolites such as SCFAs, tryptophan products, and bile acids impact mucosal immunity; how immune signals shape brain function via cytokines, microglia activation, and influence neuropsychiatric outcomes. Also, how brain/immune states feed back to alter gut ecology.

Halabitska, I., et al. (2024). “The interplay of gut microbiota, obesity, and depression.” Cellular & Molecular Life Sciences.

This article reviews how obesity, depression, and gut dysbiosis are tightly interlinked. Key findings: in obesity, microbial diversity tends to drop; certain bacterial genera (e.g. Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, decreased Prevotella or increased Alistipes, etc.) correlate with mood symptoms. Also, obesity‑associated gut barrier disruption increases circulating lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which activates systemic inflammation, which is tied to depression or anxiety. Lifestyle, diet, stress, antibiotics all shift this balance.

Other studies (e.g. Medina‑Rodríguez et al., Verma et al., Marano et al.) exploring microbiome‑barrier‑immunity‑brain communications similarly confirm that mood disorders correlate with gut barrier impairment, immune activation, decreased SCFA production, altered microbial composition, etc. Although many of these are cross‑sectional or preclinical, the accumulating evidence supports causal links.

What this means in practice

- Mood disorders (anxiety, depression) may be early warning signs of gut dysbiosis / immune activation, not purely “brain disorders.”

- Weight gain / obesity is not simply about calories; microbial ecology, gut permeability, endotoxin load, and immune response matter.

- Immune modulation via the gut can shift disease trajectories (autoimmune conditions, chronic inflammation, metabolic syndrome, mental health).

3.2 Foods That Secretly Damage Gut Balance

While probiotics, fiber, fermented foods often get praise, there are many common dietary (and lifestyle) exposures that damage gut balance:

Culprits & Mechanisms

- Excessive processed sugar and refined carbohydrates

- Feed opportunistic microbes / yeast, reduce microbial diversity.

- Cause rapid rises in blood sugar → reactive oxygen species (ROS) in gut lining → promote permeability.

- Promote inflammation via increasing LPS entering bloodstream (“metabolic endotoxemia”).

- Artificial sweeteners, emulsifiers, certain food additives

- Some emulsifiers (carboxymethylcellulose, polysorbate 80) have been shown in animal studies to disrupt the mucus layer, promote low‑grade inflammation.

- Artificial sweeteners may alter microbiome composition unfavorably.

- Excess saturated fat / high long‑chain fatty acid diets, low fiber

- Diets low in fermentable fiber starve beneficial microbes that produce SCFAs (butyrate, propionate, etc.). SCFAs are key for colonocyte health, anti‑inflammatory signaling, maintaining gut barrier.

- High saturated fat diets can promote growth of endotoxin producing bacteria or microbes that degrade barrier integrity.

- Frequent antibiotic use and other medications

- Antibiotics indiscriminately kill both beneficial and harmful bacteria. Repeated, broad‑spectrum antibiotic use reduces diversity.

- Other meds: proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), NSAIDs, some antidepressants may affect gut flora or permeability.

- High stress, poor sleep, lack of exercise

- Stress hormones (cortisol, CRH) modulate gut barrier, immune reactivity.

- Sleep deprivation reduces repair of gut lining; circadian misalignment influences microbial rhythms.

- Ultra‑processed foods

- Low in fiber, high in additives, high in refined fats, and simple sugars.

- Often high in trans fats or unhealthy fats that promote inflammation.

Hidden Damage Examples (Narrative)

- Someone might eat “healthy” in terms of low fat and moderate calories but rely heavily on ultra‑processed packaged foods, flavored yogurts, sodas, refined grains → their fiber is insufficient, their microbiome diversity diminished, leading to mood swings, poor immunity, bloating.

- Or someone using PPIs long‑term may have reduced stomach acid → altered microbial populations, increased risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), impaired protein digestion, downstream metabolic and immune effects.

3.3 The 3 Daily Habits to Restore a Thriving Gut

Based on recent mechanistic findings and clinical data, here are three daily habits you can adopt (or deploy with clients) to restore gut health. These are deliberately simple, maximally impactful, and evidence‑backed.

Habit 1: Feed the Good Microbes (Fiber, Prebiotics, Fermented Foods)

- Goal: Increase fermentable fiber intake (i.e. prebiotics) to promote SCFA production (especially butyrate, propionate) which support immune regulation, mucosal repair, and anti‑inflammatory signaling.

- How:

- Include several servings per day of high‑fiber vegetables, legumes, whole grains (if tolerated), nuts, seeds.

- Add prebiotic‑rich foods (e.g. onions, garlic, asparagus, Jerusalem artichoke, chicory root).

- Incorporate fermented foods (e.g. sauerkraut, kimchi, kefir, yogurt with live cultures) to help reseed beneficial microbes.

- Evidence: Park & Han (2025) emphasize SCFAs as central in gut‑immune modulation. The obesity/depression review (Halabitska et al.) notes low SCFA producers correlate with mood and metabolic dysregulation.

Habit 2: Protect and Repair the Barrier (Reduce Gut Permeability / Inflammation)

- Goal: Prevent or heal damage to the gut mucosa that lets unwanted molecules (LPS, microbes) leak into circulation, provoking immune activation.

- How:

- Avoid chronic irritants: reduce or eliminate refined sugar, processed foods, food additives/emulsifiers.

- Use nutrients known to support barrier integrity: glutamine, zinc, vitamin A, polyphenols.

- Avoid unnecessary antibiotic use; consider taking probiotics or microbial diversity supplements when antibiotic use is unavoidable.

- Manage stress and sleep: since stress/cortisol and sleep loss both degrade barrier integrity (via immune dysregulation).

- Evidence: The Medina‑Rodríguez et al. review (2024) highlights how intestinal barrier dysfunction is strongly connected to mood via immune activation. Also obesity/depression reviews indicate that endotoxin translocation (triggered by barrier damage) is upstream of inflammation and mood/metabolic changes.

Habit 3: Modulate Microbiota through Lifestyle & Therapeutics

- Goal: Shift gut microbial community toward balance: more beneficial bacteria, less pathologic taxa; improve immune signaling; reduce metabolic endotoxemia.

- How:

- Diet as therapy: Mediterranean‑style diet (high in plant diversity, fibers, polyphenols, moderate healthy fats) has been repeatedly shown to support microbial diversity, SCFA production, reduce inflammation.

- Probiotics / prebiotics or synbiotics (combinations) when warranted; strain specificity matters (e.g. Bifidobacteria, Lactobacillus, but others like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Akkermansia muciniphila, etc.).

- Controlled fasting / meal timing where appropriate: giving the gut periods of rest influences microbial diurnal rhythms (preclinical data).

- Physical activity: regular moderate exercise supports gut diversity, reduces inflammatory markers.

- Reduce toxin / pollutant exposures (pesticides, food contaminants) and avoid excessive medications that harm microbiome (antibiotics, PPIs, NSAIDs) unless medically needed.

- Evidence: The Halabitska review shows that lifestyle modifications (diet, exercise) are among the most consistent ways to modulate microbiota in obesity + depression. Park & Han emphasize possibilities of microbiota‑derived biomarkers, personalized interventions.

Case Studies

To make these habits concrete, here are two cases (fictional but realistic) that illustrate how someone might implement these three gut‑restoring habits and what outcomes to expect.

Case Study A: “Sara,” Age 32 — Mood Instability, Weight Gain, Low Energy

Background:

- Sara has gained ~15 lbs over 3 years despite attitude of “healthy diet” (lean meat, carbs, low fat, but many processed foods).

- Frequently feels anxious, low mood part of month, bloated after meals, occasional diarrhea, low immunity (frequent colds).

Assessment:

- Gut microbiome testing shows reduced diversity, low SCFA producers (low Faecalibacterium, Roseburia), increase in pro‑inflammatory species.

- Diet diary shows low fiber (mostly from rice, bread), little fermented food.

- Sleep often interrupted; high stress job.

Implementation:

- Increase daily fiber: few extra vegetables, legumes; add prebiotic foods (onion, garlic).

- Two servings fermented foods weekly.

- Remove processed snacks (chips, candy); eliminate or reduce artificial sweeteners.

- Use glutamine + zinc supplement for 4 weeks.

- Stress management: 10 minutes evening meditation; improve sleep environment.

- Moderate exercise 30 min, 4×/week.

Outcomes (after ~8‑12 weeks):

- Bloating reduced; digestion more regular.

- Mood more stable; fewer anxiety spikes.

- Slight weight reduction (~5‑7 lbs) without calorie counting.

- Energy improved; fewer infections.

Case Study B: “Mike,” Age 45 — Obesity, Depression, Metabolic Drift

Background:

- Mike has BMI ~32, has been on antidepressants for mild depression, poor sleep, often eats late, large dinners; frequent fast food; sedentary job.

Assessment:

- Microbiome shows low fiber fermenters; elevated prevalence of LPS‑producing bacteria.

- Markers of inflammation elevated (CRP, IL‑6); likely leaky gut.

- Mood symptoms: low motivation, fatigue; weight gain especially abdominal; cravings.

Implementation:

- Shift diet to Mediterranean: more plants, legumes, whole grains, healthy fats (olive oil, nuts), reduce red and processed meats.

- Add probiotic supplement (well researched strains) + prebiotic fiber.

- Early dinner (before 7 pm), avoid late night snacking.

- Regular movement: walking, resistance training.

- Sleep hygiene.

Outcomes (after 3‑4 months):

- Weight plateau then gradual loss.

- Reduced inflammation markers.

- Less depression symptoms; more energy.

- Cravings decrease; appetite more normal.

Practical Guide: Putting Gut Health into Daily Routine

Here is a daily/weekly habit plan drawn from the three core habits, which can be adapted for individual contexts.

| Time | Habit | Specific Action |

| Morning | Movement & exposure | 10‑15 min brisk walk; sunlight exposure; include some probiotic (fermented) food if desired for breakfast |

| Mid‑day | Fiber & plant diversity | Lunch rich in vegetables, legumes; use various colors; include antioxidant‑rich produce |

| Afternoon | Reduce stress / rest | Short break; avoid high sugar snacks; herbal tea rather than empty calories |

| Evening | Early dinner; avoid irritants | Finish last meal 2‑3 hours before bed; avoid heavy, fried, ultra-processed foods; limit alcohol |

| Night | Gut pipeline repair | Small post‑biotics or fermented snack if needed; ensure sleep hygiene; manage stress; avoid sleep disruption |

| Weekly | Deep repair protocol | One day of more substantial fermented food; possibly a gut healing protocol (e.g. with glutamine, zinc) if symptoms or testing indicate; review gut symptoms (bloating, stool quality, mood) and adjust diet accordingly |

Integrative Implications & Forward Paths

- Personalization is essential: Each person’s microbiome baseline, history (antibiotics, diet, childhood), genetic susceptibilities, stress exposures differ. A habit that works for one may be less effective in another. Testing (microbial, immune, barrier integrity) may help guide interventions.

- Early life matters: Park & Han (2025) emphasize that early‑life microbiota establishment, immune training (neonatal, infancy, early childhood) are critical windows. Interventions in adulthood are still powerful, but early imbalances may seed long‑term vulnerability.

- Diet + lifestyle synergy: Diet alone helps, but sleep, stress, exercise, environment all modulate gut health. For example, sleep loss exacerbates gut permeability, stress dysregulates immune responses to gut‑derived antigens. These need to be addressed in combination.

- Emerging therapeutics: Microbiota‑derived biomarkers (SCFAs, tryptophan metabolites), probiotics / synbiotics, possibly fecal microbiota transplantation (in certain diseases), microbiome interventions tailored to individual microbial signatures. Park & Han point to future of precision microbiome‑immune interventions.

- Tracking & feedback: Monitoring stool quality/composition, symptoms (bloating, mood, energy, immunity), possibly microbial diversity (where available), markers of inflammation (CRP, IL‑6), metabolic markers (glucose, lipids) to observe shifts.

Part 4: Hormones in Harmony

Balance your inner chemistry—naturally, powerfully, sustainably.

Hormones are the biochemical conductors of your body’s orchestra. When in harmony, they coordinate energy, metabolism, mood, growth, repair, and immunity. When out of sync, they trigger cascades that lead to weight gain, fatigue, mood disorders, metabolic disease, and worse. In this section, we examine:

- 4.1 Signs your hormones are crying for help

- 4.2 Insulin, cortisol, and thyroid: the overlooked triangle

- 4.3 Natural ways to rebalance hormones without drugs

We draw on recent human studies—especially those published in 2024‑2025—and weave case examples and practical frameworks so you can both understand and apply.

4.1 Signs Your Hormones Are Crying for Help

Hormonal imbalance often begins subtly. Most people ignore the warning signs until more obvious symptoms or diagnoses emerge. Key early indicators include:

- Fatigue, low energy, difficulty recovering – even with adequate sleep, you may feel drained; workouts may feel harder, recovery slower.

- Weight gain (especially belly fat), difficulty losing weight – often unresponsive to diet alone.

- Mood instability, brain fog, depression or anxiety – memory slips, inability to concentrate.

- Sleep disturbances – insomnia, fragmented sleep, poor sleep quality despite enough hours.

- Irregular periods, low libido, or sexual dysfunction – in women and men, respectively.

- Cold intolerance, sensitivity to temperature, dry skin, hair loss – those are often thyroid signals.

- Elevated blood sugar, insulin resistance‑type signs: sugar cravings, post‑meal fatigue, rising fasting glucose.

Recent Studies Highlighting Early Signs

- Mehran, L., et al. (2025). Association between central thyroid hormone sensitivity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The Tehran Thyroid Study showed that in people who are euthyroid (normal thyroid hormone levels), decreased central thyroid hormone sensitivity (as measured by indices like TSHI, TT4RI, PTFQI) was correlated with lower risk of prediabetes. Conversely, deviations—i.e. reduced sensitivity—seem to precede and predict glucose regulation problems.

- Malhotra, A., et al. (2025). Irisin and Insulin Interplay in Thyroid Disorders: A Pilot Study. This small study (hypothyroid, hyperthyroid, euthyroid groups) found altered levels of Irisin in thyroid disorders, correlated with insulin changes. Specifically, Irisin levels declined in hypothyroid individuals, and hyperthyroid states showed increased insulin but a negative correlation with Irisin. These molecular shifts are early clues that hormonal dysregulation is proceeding.

4.2 Insulin, Cortisol, and Thyroid: The Overlooked Triangle

These three are deeply interconnected. Insulin, cortisol, and thyroid hormones form a triangle of control—each one influences the others. Disruption in one often cascades to dysfunction in the others.

How They Interact

- Insulin regulates blood sugar and energy storage/use. When insulin resistance rises (the body requires more insulin to get same effects), fat storage often increases, energy dips occur, glycemic control worsens.

- Thyroid hormones modulate basal metabolic rate, thermogenesis, lipid metabolism, and glucose usage. Thyroid hormone sensitivity (both central and peripheral) determines how well tissues respond to T3/T4 and how efficiently the body produces or uses them. Reduced sensitivity can mean normal hormone levels but functional hypothyroid effects in tissues.

- Cortisol (and the broader HPA axis) responds to stress. Elevated or poorly regulated cortisol (especially chronically high or erratic) impairs insulin sensitivity, suppresses thyroid conversion (T4 → T3), increases inflammation, and can contribute to fat accumulation—particularly visceral fat.

Findings from Recent Human Research

- Central Thyroid Hormone Sensitivity & Prediabetes: Mehran et al. (2025) found that people with higher indices of thyroid hormone resistance (that is, reduced sensitivity centrally) had lower odds of prediabetes in some contexts, but also that deviations from “normal” sensitivity (both residual resistance or overactivity) are associated with glucose dysregulation. This suggests that what’s often labeled “euthyroid” may mask early inefficiencies in hormone action.

- Impaired Central TH Sensitivity & Time in Range (T2DM): A study by Xu Jiang et al., 2025, in Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome found that among euthyroid T2DM patients, central TH sensitivity indices (TSHI, TT4RI, TFQI) correlated with how well patients maintained blood glucose in the target range. Those with more “resistance” (i.e. lower sensitivity) had different glycemic dynamics.

- Irisin‑Insulin in Thyroid Disorders: The pilot study by Malhotra et al. found thyroid status influences insulin & Irisin relationships. Irisin is a myokine—released by muscle during physical activity—that can promote browning of fat and improve metabolic function. Changes in Irisin levels relative to thyroid status suggest that thyroid disorders can undercut this beneficial hormone’s effect, contributing to metabolic imbalance.

Putting It Together: Early Warning Signs & the Triangle

These interaction patterns suggest that:

- Normal thyroid hormone levels do not guarantee optimal hormonal function—if sensitivity is reduced, tissues don’t “see” the hormones well.

- High cortisol (from stress, sleep loss, circadian misalignment) exacerbates insulin resistance and suppresses thyroid conversion.

- Insulin resistance and high insulin can feed back negatively on thyroid hormone metabolism and also increase cortisol burden.

4.3 Natural Ways to Rebalance Hormones Without Drugs

While drug therapy has its place (especially in overt disease), much hormonal disharmony can be addressed with lifestyle, dietary, behavioral, and supplement‑adjunct approaches. The following strategies are supported by recent evidence; some RCTs, some pilot/human observational studies, plus physiological reasoning.

Strategy A: Improve Thyroid Hormone Sensitivity

- Adopt moderate, regular physical activity, particularly strength training and interval work. Exercise increases expression and translocation of glucose transporters (GLUT4), improves insulin sensitivity, and enhances mitochondrial function—all of which improve tissue responsiveness to thyroid hormones.

- Ensure adequate micronutrients essential for thyroid hormone production and conversion: selenium (for deiodinases), zinc, iodine, iron, vitamin A. Also support with adequate protein and healthy fats.

- Address stress and sleep: Cortisol free‑rises or chronic elevations suppress the conversion of T4→T3 and promote reverse T3; poor sleep similarly disrupts HPT (hypothalamic‑pituitary‑thyroid) feedback loops. Deep, continuous sleep and circadian regularity help.

- Avoid endocrine disruptors where possible: chemicals in cosmetics, plastics (e.g. BPA), heavy metals can interfere with thyroid hormone receptors, transport, or conversion.

Strategy B: Regulate Insulin and Reduce Insulin Resistance

- Diet: emphasize low glycemic load carbohydrates; increase fiber; reduce refined sugar & high fructose → improves insulin response, reduces demand on insulin.

- Meal timing / intermittent fasting (or time‑restricted eating) where feasible: giving the pancreas / insulin system rest, lowering basal insulin levels while maintaining energy balance.

- Healthy fat inclusion: omega‑3 fatty acids, monounsaturated fats; avoid trans fats and overly saturated fats.

- Maintain lean muscle mass via strength training: muscle is a major sink for glucose → better insulin sensitivity.

Strategy C: Cortisol / HPA Axis Modulation

- Stress reduction rituals: mindfulness, meditation, breathwork; these reduce baseline cortisol, reduce overactivation.

- Adaptogenic herbs (with good evidence and under supervision): ashwagandha, Rhodiola, etc. These may help buffer stress responses.

- Ensure consistent sleep routines: earlier bedtimes, darkness, reduce light/stimulation in evenings. Sleep architecture restoration helps in calibrating cortisol rhythm.

- Physical activity is also a double‑edged sword: too much intense exercise without recovery can increase cortisol; moderate and balanced training both supports metabolic health and helps modulate cortisol.

Illustrative Case Studies

Here are two cases showing how applying these strategies can rebalance the insulin‑thyroid‑cortisol triangle.

Case Study 1: Euthyroid but Hormone Resistance (“Sara” Age 40)

Background:

- “Sara” has normal thyroid labs (TSH, FT4, FT3 within standard range), but elevated TSH responsiveness indices (measured via TSHI & TT4RI) suggest tissue resistance. She has difficulty losing weight, elevated fasting glucose (~105 mg/dL), fatigue, moderate sleep disturbance, often stressed at work.

Intervention Plan:

- Diet: Lower glycemic load, increase fiber, lean protein, healthy fats. No late night carbs.

- Exercise: Strength training 3×/week, short high intensity intervals 2×/week.

- Sleep / Stress: Fixed sleep schedule; sleep hygiene; daily 10‑min meditation or breathwork before bed.

- Micronutrient check: Ensure selenium, zinc, iron not deficient. Supplement if needed.

- Lifestyle tweak: Reduce caffeine; avoid environmental toxins (BPA plastics, etc.).

Outcomes (over 3‑6 months):

- Improved insulin sensitivity (lower HOMA‑IR), small weight loss (~5‑8 lbs), more energy.

- Subjectively, less “cold limbs,” less hair shedding; improved mood.

- Possible improvement in TSHI/TT4RI indices on repeat labs.

Case Study 2: Hyperthyroid History, Insulin Dysregulation & Cortisol Elevation (“Mark” Age 52)

Background:

- “Mark” had history of hyperthyroidism treated years ago; now euthyroid on medications, but complains of elevated fasting glucose, occasional high cortisol (salivary tests), mood swings, poor sleep.

Intervention Plan:

- Low refined sugar, balanced diet. Add more fiber, vegetables, healthy fats.

- Resistance training + moderate cardio.

- Evening wind‑down ritual: screen removal, light reduction, breathwork. Aim for deep sleep nights.

- Stress management: working with therapy or CBT for stress; adaptogens.

- Regular monitoring of glucose, perhaps continuous glucose monitoring to see “time in range.”

Outcomes (after ~4‑5 months):

- Less insulin spikes post‑meals; flatter glucose curves; better energy, mood stabilization.

- Sleep improved; fewer nighttime awakenings.

- Cortisol rhythm more normalized; lower evening readings.

Practical Hormone Rebalance Blueprint

Here is a weekly/daily regimen to optimize insulin, thyroid, and cortisol interplay—focusing on non‑drug interventions.

| Time / Domain | Action | Rationale |

| Morning | Wake at same time; light exposure; protein + fiber breakfast | Stimulate cortisol rhythm, avoid insulin spikes |

| Mid‑morning | Avoid refined sugar snacks; include healthy fats/protein | Keeps insulin stable; supports thyroid metabolism |

| Afternoon | Moderate exercise (strength or interval); avoid stress overload | Improves insulin sensitivity; uses up glucose; modulates cortisol |

| Evening | Light dinner; avoid heavy carbs; wind‑down ritual; no electronics; reduce light exposure | Supports thyroid conversion; lowers evening cortisol; aids sleep |

| Sleep | Aim for 7‑9 h; promote deep sleep; consistent schedule | Deep sleep enhances insulin control, thyroid sensitivity, cortisol reset |

| Nutrition | Ensure iodine/selenium/zinc/iron/vitamin D adequate; balanced fat; reduce processed foods | Necessary cofactors for hormonal synthesis/conversion |

| Stress | Daily practice: meditation / journaling / breathwork; weekly therapy or stress buffer | Reduce baseline cortisol; improve HPA axis feedback |

| Monitoring | Blood sugar (fasting & post‑meal), thyroid labs (TSH, FT4, FT3, antibody status), possible indices of sensitivity (if accessible), salivary cortisol or diurnal curve if indicated | To adjust interventions & detect improvements early |

Summary & Key Messages

- Hormonal harmony often breaks first in sensitivity, not always hormone levels: thyroid resistance, insulin resistance, cortisol overdrive may precede overt dysfunction.

- The triangle of thyroid‑insulin‑cortisol is foundational. Disruption in any node tends to stress the others.

- Recent studies (Mehran et al., Malhotra et al., etc.) show that even in people with “normal labs,” indices of hormone sensitivity, or molecular markers (like Irisin), correlate with metabolic dysregulation and risk of diabetes.

- Non‑drug interventions—sleep, diet, movement, stress management, micronutrient optimization—have strong evidence as first line approaches.

- Monitoring, listening to bodily signals, catching early warning signs is vital for prevention and restoration.

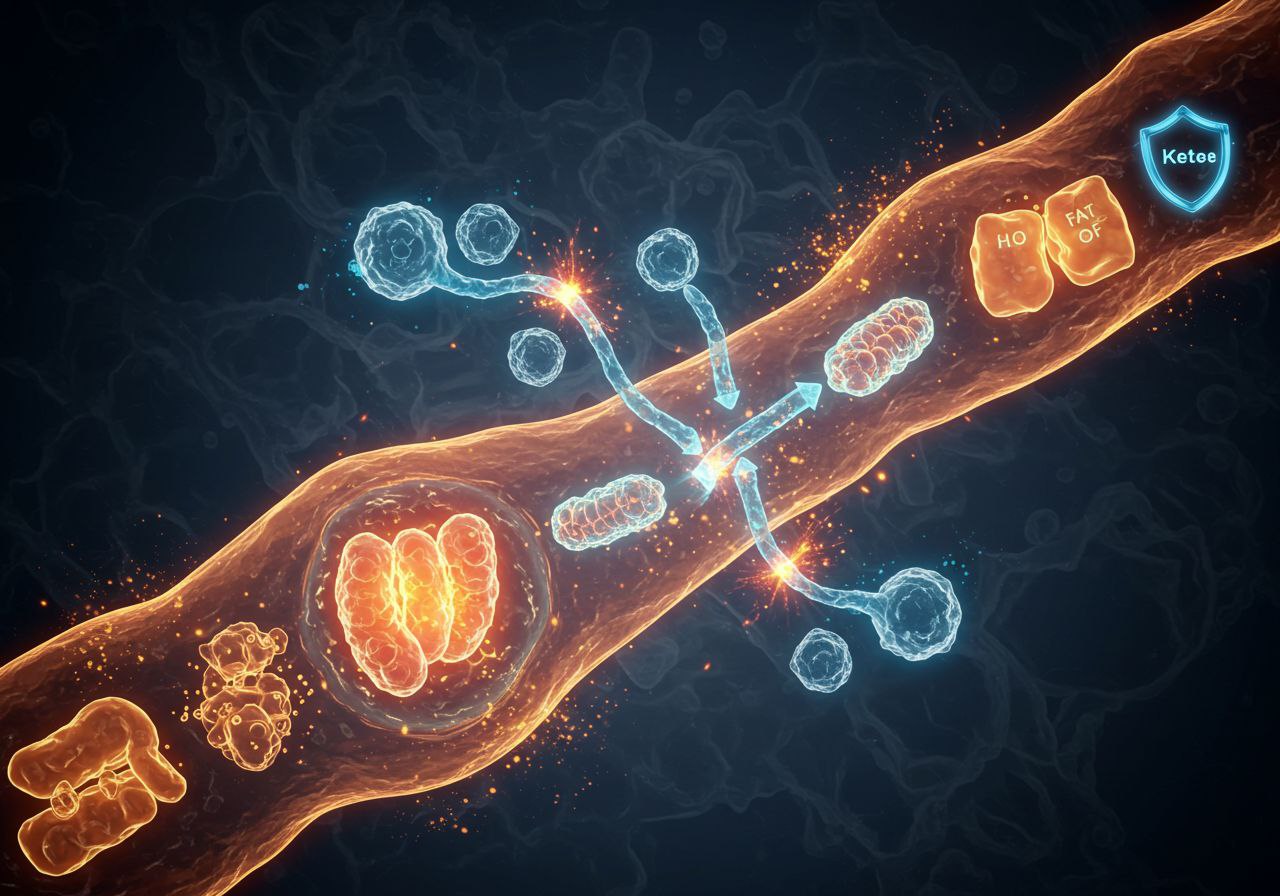

Part 5: Metabolic Firepower

Metabolic Firepower is about more than burning calories—it’s about how your body uses energy, how mitochondria produce power, and how flexible you are in switching fuel sources. Cultivating metabolic flexibility and healthy mitochondrial function is one of the most potent levers for lasting health, weight management, energy, and longevity.

5.1 Key Mechanisms: Mitochondrial Function & Metabolic Flexibility

What We Mean by Metabolic Flexibility & Mitochondrial Function

- Metabolic flexibility refers to your body’s ability to switch efficiently between fuel sources (e.g. glucose, fat, ketone bodies) depending on availability, need, and energy demand.

- Mitochondrial function involves how well mitochondria produce ATP through oxidative phosphorylation, how well they adapt (biogenesis), maintain quality (fusion/fission, autophagy/mitophagy), manage ROS (reactive oxygen species), and respond to stress.

Good metabolic flexibility implies that in fasting or low‑glucose states your body cleanly shifts into fat/ketone burning; in high demand (exercise or post‑meal), it can shift to glucose; it has good mitochondrial quantity & quality to support these shifts without over‑producing oxidative damage.

Recent Relevant Studies

Here are a few recent studies that shed light on how metabolic flexibility and mitochondrial function can be improved, or how they are impaired, with implications for interventions:

- Menezes, E. S., Islam, H., Arhen, B., Simpson, C., McGlory, C. & Gurd, B. (2024). “Impact of exercise and fasting on mitochondrial regulators in human muscle.” Translational Exercise Biomedicine, 1(3‑4), 183‑194.

This human study looked at skeletal muscle biopsies after acute high‑intensity interval exercise (HIIE) and after an 8‑hour fast. Following HIIE, there were significant increases in mRNA expression of PGC‑1α and NR4A1, key mitochondrial biogenesis regulators. Fasting for 8 hours without exercise reduced NR4A1 and NR1D1 expression, suggesting that short‑term fasting without energy demand may downregulate some mitochondrial regulators. - A. Zhang et al. (2024). “Intermittent fasting, fatty acid metabolism reprogramming …” Frontiers in Nutrition.

Found that intermittent fasting (IF) enhances mitochondrial biogenesis, reduces oxidative stress, improves neuronal protection, and increases expression of antioxidant enzymes and mitochondrial dynamics proteins. IF also promotes increased mitochondrial fusion proteins, regulation of mitophagy, and better energy homeostasis. - Frontiers review: Gut microbiota–mitochondrial crosstalk in obesity (L. Wen et al., 2025).

This review explores how gut microbiota affects mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, biogenesis, and autophagy, especially in obesity. It also discusses how mitochondrial dysfunction in hosts feeds back on microbial ecology. - “Multiple pathways through which the gut microbiota … regulates neuronal mitochondrial function” (Zhao et al., 2025).

Focused especially on how gut microbial metabolites, immune modulation, and gut barrier function influence neuronal mitochondrial health. It draws connections between depression (or mood disorders) and impaired neuronal mitochondria, mediated by gut dysbiosis. - Diet & Physical Exercise in MASLD (Metabolic dysfunction‑associated steatotic liver disease) Intervention (SP Mambrini et al., 2024).**

They examine how interventions involving diet and exercise improve mitochondrial metabolism and metabolic flexibility in humans with MASLD. Among other measures, they show improved expression of PGC‑1α and improved mitochondrial function metrics.

5.2 How Metabolic Firepower Gets Lost

Understanding how we lose metabolic flexibility helps target what to restore. Key causes:

- Sedentary lifestyle → reduced mitochondrial density & capacity; muscle becomes less able to oxidize fat.

- Over‑reliance on high‑glycemic or processed food → frequent insulin spikes, elevated glucose, suppression of fat oxidation, possibly “glycolytic” metabolic profile.

- Chronic overnutrition / obesity → mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, reduced mitochondrial biogenesis; some muscle fibers shift toward less oxidative phenotypes. (E.g. in MASLD, obesity studies)

- Poor sleep, circadian misalignment → interferes with mitochondrial repair & gene expression cycles.

- Gut dysbiosis and inflammation → endotoxin exposure, immune activation, ROS, mitochondrial damage. Reviews (e.g. Wen et al., Zhao et al.) document the crosstalk between gut microbiota and mitochondrial health; in obesity there’s evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction is tied to microbial imbalance.

- Aging – baseline mitochondrial function declines; capacity to induce biogenesis diminishes.

5.3 Practices That Supercharge Metabolic Flexibility & Mitochondrial Power

Drawing on these studies plus established literature, here are practices (daily/weekly) that have strong evidence for boosting mitochondrial biogenesis, improving metabolic flexibility, minimizing damage, and restoring resilience.

Practice A: High‑Intensity / Variable Exercise + Strength Training

- Why: HIIE (High‑Intensity Interval Exercise) produces strong upregulation of genes like PGC‑1α, NR4A1, etc. — key mitochondrial biogenesis regulators. Menezes et al. 2024 found acute HIIE raises PGC‑1α and NR4A1 significantly.

- How to Apply:

- Include 1–2 sessions per week of high intensity interval training (e.g. cycle sprints, hill sprints, circuit training) for 20‑30 minutes.

- Strength training 2‑3×/week to build muscle mass (muscle is mitochondria‑rich tissue).

- Active recovery days with gentle movement (walking, yoga) to support mitochondrial repair.

Practice B: Intermittent Fasting / Time‑Restricted Eating

- Why: IF has been shown to increase mitochondrial biogenesis (via AMPK, SIRT1 activation), reduce oxidative stress, promote mitochondrial dynamics (fusion/fission), improve autophagy, etc. (Zhang et al., 2024 IF study)

- How to Apply:

- Choose a fasting window (e.g. 14‑16 hours nightly, or 10‑16 window depending on schedule).

- Avoid late‑night eating; front‑load calories earlier in day.

- Pair fasting with physical activity when possible (e.g. morning fasted movement), but ensure nutrition support when training intensely.

- Caveats: For some people (e.g. metabolic disease, older age, undernourished), need to proceed carefully; ensure protein adequacy; monitor any adverse effects.

Practice C: Improve Diet for Mitochondrial Support

- Nutrients that support mitochondrial health:

- Polyphenols / antioxidants (e.g. resveratrol, flavonoids) — protect mitochondria from ROS.

- CoQ10, PQQ, L‑carnitine, magnesium, B‑vitamins, omega‑3 fats.

- Foods rich in mitochondria‑supporting compounds: green tea, berries, nuts, oily fish, dark leafy greens.

- Eat with appropriate macronutrient mix; avoid excessive refined sugar; balance fats (avoid trans fats; get enough saturated vs unsaturated balance).

Practice D: Gut Health & Microbiome Modulation

- Because gut microbiota produce metabolites (like SCFAs, secondary bile acids) which influence mitochondrial biogenesis, oxidative metabolism, mitochondrial autophagy. Wen et al. (2025) review makes clear: altering gut composition can boost mitochondrial efficiency in obesity.

- Include fermented foods, prebiotics, fiber, reduce gut irritants, ensure barrier integrity.