“When prevention is buried, we dig.”

By Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

Investigative Journalist | Public Intellectual | Global Governance Analyst | Health & Social Care Expert | International Business/Immigration Law Professional

Executive Summary

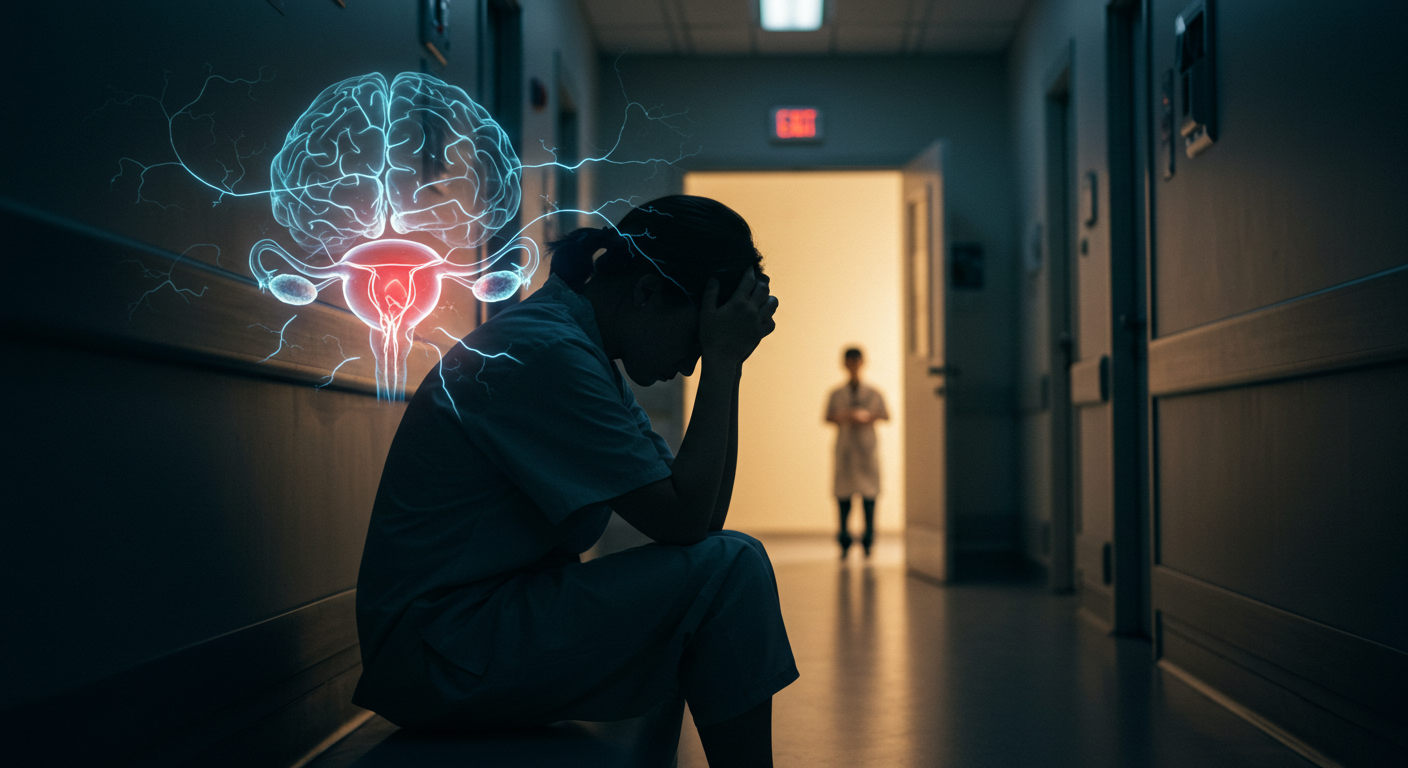

Infertility is no longer a marginal issue; it is a defining public health challenge of the 21st century. Affecting one in six couples globally, its roots extend far beyond biology, implicating lifestyle, environment, psychology, and cultural silence. This twelve-part investigative series, Breaking Infertility: Natural Paths for Women’s Health, maps a new paradigm—one that transcends narrow biomedical fixes and instead situates fertility within a holistic ecosystem of body, mind, and society.

We begin by dismantling myths: infertility is not solely a woman’s burden, nor simply a matter of “bad luck.” Part 1 uncovers overlooked causes, while Part 2 details the fragile symphony of estrogen and progesterone. Parts 3 through 6 explore nutrition, weight balance, stress regulation, and sleep—pillars often neglected in clinical practice but proven to influence ovulation, implantation, and ovarian reserve.

Environmental and cultural realities deepen the crisis. Part 7 reveals endocrine disruptors and even microplastics infiltrating ovarian follicles. Part 8 revisits traditional and herbal remedies, showing how ancient formulations now stand on a growing base of modern evidence. In Part 9, the microbiome emerges as a revolutionary frontier—linking gut health with estrogen metabolism, immune tolerance, and reproductive resilience.

Crucially, Part 10 reframes male factor infertility, responsible for up to half of all cases, as both a reproductive and systemic health indicator. Part 11 turns to the hidden emotional toll, where anxiety, relationship strain, and social isolation demand community, therapy, and shared storytelling as much as medical intervention. Finally, Part 12 sketches a roadmap—integrating nutrition, sleep, detoxification, faith, and functional diagnostics alongside assisted reproduction—to restore fertility through wholeness rather than fragmentation.

The series argues that infertility is not a single diagnosis but a systems disorder, where physiology, psychology, and environment converge. Treating only the ovaries or the testes without addressing stress, sleep, toxins, or resilience is not just incomplete—it is ineffective. True fertility care must be integrative, evidence-based, and compassionate, respecting both science and lived experience.

Breaking Infertility concludes with a call to action: fertility restoration is not about chasing technology alone, but about rebalancing human beings in their entirety—biological, emotional, environmental, and spiritual. Only then can the path to conception become not just possible, but sustainable.

Part 1: Understanding Infertility Beyond the Myths

Shedding light on the real causes hidden behind silence.

1.0 Introduction: Unmasking Infertility

Infertility has long existed under the shadow of myths, shaped by stigma and oversimplified medical models. While mainstream discourse often blames age or genetics, current research paints a far more intricate picture—one deeply influenced by nutrition, oxidative stress, lifestyle patterns, environmental toxins, and post-viral effects.

This section presents an evidence-rich, myth-busting narrative to redefine how infertility is understood, diagnosed, and treated in modern contexts.

1.1 Debunking the Singular Cause Myth

1.1.1 Infertility as a Multifactorial Condition

As Jeon (2025) asserts in Reproductive Health, infertility cannot be isolated to a single organ system or pathology. Instead, it functions as a systems-level response—where metabolic health, inflammation, hormonal rhythm, and environmental exposure intersect to suppress reproductive capacity.

“Lifestyle factors,” Jeon (2025, p. 30) argues, “are not peripheral but central to the fertility equation.”

This reconceptualization moves infertility from a deterministic model toward one that emphasizes physiological adaptation to stress—a protective mechanism, not a pathology.

1.2 Oxidative Stress: The Silent Fertility Blocker

1.2.1 Oxidative Balance Score (OBS) and Fertility Outcomes

Xia (2025), in Frontiers in Endocrinology, introduces the concept of the Oxidative Balance Score (OBS)—a measure encompassing antioxidant intake, physical activity, alcohol use, and sleep quality. Her findings show a strong inverse correlation between oxidative stress and successful conception rates.

Lei (2024) reinforces this in Frontiers in Nutrition, showing that women in the highest OBS quartile had significantly lower rates of ovulatory dysfunction and unexplained infertility.

These studies dismantle the myth that fertility outcomes are random. Instead, they show infertility is often a biochemical expression of long-term imbalance, influenced by cellular oxidative stress.

1.3 Nutritional Intelligence: Beyond Prenatal Vitamins

1.3.1 The Micronutrient-Fertility Link

In Scientific Reports, Zhao (2025) demonstrates that vitamin B2 (riboflavin) intake is directly associated with improved fertility outcomes. His study controls for variables such as age and BMI, revealing that even modest increases in B2 can support hormonal regulation and egg quality.

Similarly, Martín-Manchado (2024) explores how poor nutrient absorption—even in the context of adequate intake—can sabotage fertility. Her research links gut inflammation and dysbiosis to nutrient malabsorption, challenging the one-size-fits-all supplement model.

Together, these findings advance a precision nutrition paradigm, where fertility care is tailored to biochemical individuality, not broad generalizations.

1.4 Rethinking “Unexplained” Infertility

1.4.1 Prognosis-Based Diagnosis over Static Labels

Shingshetty (2024), writing in Human Reproduction Open, critiques the term “unexplained infertility” as a diagnostic failure, not a clinical reality. She calls for a prognosis-based approach, which integrates data from lifestyle, environment, microbiome, and hormone rhythm assessments.

“Unexplained infertility is often unexplored infertility,” Shingshetty argues, pointing to the system’s failure to assess beyond surface-level diagnostics.

This model shifts focus toward functional health optimization, enabling many couples to achieve conception without resorting to invasive interventions like IVF.

1.5 The Pandemic’s Shadow: COVID-19 and Fertility

1.5.1 Post-Viral Effects on Female Reproductive Health

Yousif et al. (2023), in a preprint hosted on arXiv, provide one of the first comprehensive reviews of post-COVID reproductive disruption. Their findings suggest that COVID-19 may trigger:

- Hypothalamic inflammation

- Disrupted ovulation cycles

- Temporary ovarian dysfunction

These effects often linger for months post-recovery, adding a new layer to the modern fertility landscape. Importantly, the study points to the need for immune-supportive interventions in fertility care—ranging from anti-inflammatory diets to immune-regulating supplements.

1.6 The Myth of Female Blame in Infertility

Although men contribute to roughly 40–50% of infertility cases, women continue to bear the cultural and clinical burden. Much of the research in this exposé focuses on women’s health, but it is crucial to recognize that the pathologization of the female body is a legacy of biased medical frameworks.

This series will later address male-factor infertility (see Part 10), but for now, it is critical to begin by unlearning the ingrained assumption that infertility is “hers to solve.”

1.7 Summary: Toward a Systems-Based Model of Fertility

The collective findings of Jeon (2025), Xia (2025), Lei (2024), Zhao (2025), and others point to one profound truth: infertility is often an emergent symptom of broader systemic imbalance—not a definitive, unchangeable diagnosis.

Rather than viewing the body as broken, these studies invite us to view it as wise—reacting appropriately to chronic inflammatory, environmental, and emotional stressors. By shifting from symptom suppression to root cause restoration, we can move toward a fertility model that is not only more humane, but more effective.

Part 2: Hormonal Harmony and Fertility in Women

How balancing estrogen and progesterone can restore natural cycles.

Hormonal imbalance is not a niche diagnosis; it is an invisible epidemic. In a world where stress, synthetic hormones, disrupted sleep, and chemical exposure interfere with our most intimate biological processes, the endocrine system has become both battlefield and casualty. This exposé decodes the hormonal architecture behind female fertility—and why it’s collapsing under modern pressures.

2.0 Introduction: The Forgotten Foundation of Fertility

Fertility is impossible without hormonal rhythm. Every viable cycle, every ovulation, every successful implantation hinges on a delicately timed hormonal sequence, orchestrated primarily by estradiol and progesterone, but also modulated by luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), cortisol, and insulin. When that sequence falters—by seconds or degrees—reproductive capacity suffers, even in women who are still menstruating regularly.

Yet, conventional fertility diagnostics rarely look closely at these dynamic hormones outside of snapshot blood panels. Few explore their fluctuation, interaction, or timing in the luteal and follicular phases. As a result, women are often misdiagnosed, under-tested, or offered invasive interventions before simpler, system-level imbalances are addressed.

In this deep dive, we dissect the emerging research that points to hormonal imbalance—not reproductive decline—as one of the most modifiable causes of infertility.

2.1 Estradiol and Progesterone: The Twin Pillars of Female Fertility

2.1.1 More Than Menstrual Hormones

Estradiol and progesterone are not just cycle regulators; they are gatekeepers of conception. Estradiol promotes follicular maturation, endometrial proliferation, and the LH surge that triggers ovulation (Cable, 2023). Progesterone prepares the uterine lining for implantation and maintains early pregnancy until placental hormone production takes over.

In a landmark randomized controlled trial, Mørch et al. (2025) demonstrated that deviations in estradiol and progesterone—either too early, too low, or misaligned—are strongly associated with implantation failure in frozen embryo transfers (FET). This evidence reinforces that fertility treatments that do not recreate natural hormonal rhythms risk undermining their own success.

2.2 The Temporal Precision of Hormonal Interaction

2.2.1 Timing Is Not a Detail—It’s the Design

Hormones do not operate in isolation; they signal in waves, with precise peaks and troughs. Estradiol must rise to a critical threshold to trigger the LH surge and subsequent ovulation. Progesterone must rise after ovulation and remain elevated during the luteal phase to support implantation.

Jahromi et al. (2024), in a systematic review, found that the timing of progesterone initiation in FET cycles profoundly influenced success rates. Initiating progesterone too soon—before estradiol has reached peak proliferative effect—results in premature endometrial advancement, desynchronizing the uterine environment from the embryo’s developmental stage. In natural conception, this phenomenon is equally damaging but often missed in standard fertility workups, as progesterone is rarely mapped across the luteal phase.

2.3 Ovulation Prediction: Precision vs. Probability

2.3.1 LH Strips Are Not Enough

Despite the centrality of ovulation to conception, most women are advised to rely on over-the-counter LH kits that provide only a binary readout of a complex hormonal cascade. Maman (2023), in Scientific Reports, reveals that ovulation prediction is still chronically misunderstood—even in clinical settings. LH surges vary widely in length, amplitude, and synchronicity with ovulation, particularly in women with subclinical hormonal imbalance.

The implication? Many women are missing their true fertile window, even if they receive a “positive” test result. Furthermore, many may be experiencing anovulatory cycles despite apparent menstrual regularity. Maman advocates for multi-hormone fertility tracking, including estradiol and progesterone, which—although more complex—could significantly enhance diagnostic accuracy in natural and assisted conception.

2.4 Hormonal Balance Is Nutrient-Dependent

2.4.1 The Micronutrient Matrix

The endocrine system does not operate in a vacuum. Hormone synthesis, conversion, detoxification, and receptor sensitivity are all contingent upon nutrient availability, especially minerals such as magnesium, zinc, selenium, and iodine.

Kapper (2024), in a mechanistic review published in Nutrients, outlines the mineral requirements of the menstrual cycle with unprecedented clarity. For example:

- Zinc and magnesium are cofactors in progesterone synthesis.

- Selenium supports the thyroid axis, which influences cycle regularity.

- Iodine modulates estrogen receptor activity, affecting tissue sensitivity.

Kapper’s findings emphasize that many cases of hormonal dysfunction are nutrient-mediated, and that dietary interventions should be front-line treatments, not afterthoughts, in fertility restoration.

2.5 Hormonal Chaos in a Chemically Saturated World

2.5.1 Endocrine Disruptors and Synthetic Mimicry

Environmental estrogens, or xenoestrogens, found in plastics (BPA), cosmetics (parabens, phthalates), and even food packaging, mimic estradiol and bind to estrogen receptors with non-natural timing and potency. The result is biochemical chaos: estrogen dominance, progesterone suppression, and increased risk of cycle irregularity.

Segarra (2023) highlights this in her critical piece on hormonal autonomy in Frontiers in Medicine, arguing that hormonal imbalance today is not a “natural variation” but a consequence of exposure to an unnatural environment. Her feminist framing demands that hormonal health be recontextualized as both a public health issue and a matter of bodily sovereignty.

“When women are told their hormones are the problem, but their world is saturated with synthetic interference, we are treating symptoms while ignoring causes.”

—Segarra (2023)

2.6 Progesterone: The Unsung Hormone of Conception

2.6.1 Why You Can’t Implant Without It

Progesterone’s role in pregnancy is often overshadowed by estrogen, but its importance is no less vital. Without sufficient mid- to late-luteal progesterone, the endometrium cannot properly mature, and even a genetically perfect embryo will fail to implant.

Cable (2023), in StatPearls, synthesizes this: progesterone reduces myometrial contractions, promotes endometrial gland secretion, and maintains uterine quiescence during early pregnancy. Without it, luteal phase defects can result—even if ovulation and fertilization occur successfully.

Yet few clinicians test for progesterone more than once per cycle, and even fewer track its rise and fall to detect deficiencies or abnormalities. The lack of monitoring has led to misdiagnosis of unexplained infertility, when the cause may simply be low or mistimed progesterone production.

2.7 Hormonal Testing: Flawed Snapshots in a Dynamic System

2.7.1 The Limits of Day-3 and Day-21 Labs

Standard hormone panels—estradiol on day 3, progesterone on day 21—assume textbook cycles of 28 days and perfect ovulation. But real cycles are far more variable. A woman who ovulates late will show false low progesterone if tested too early; another may ovulate without producing adequate estradiol, and no single blood test will capture that dysfunction.

Mørch et al. (2025) demonstrated that hormonal misalignment, rather than absolute hormone deficiency, was often the decisive factor in failed implantation. This suggests a need for serial or mapped hormone testing, particularly for women over 30 or with irregular cycles.

2.8 Animal Models and the Reversibility of Hormonal Imbalance

2.8.1 Hope Through Restoration

Boyle (2024), in Frontiers in Reproductive Health, used animal models to test the effect of restoring physiological estradiol in hormonally suppressed females. The result? A marked decrease in implantation failure and re-synchronization of the uterine-embryo dialogue. While translational gaps exist, the study reinforces a hopeful message: hormonal imbalance is reversible, and fertility is often recoverable without invasive techniques—if the timing and support are right.

2.9 Stress, the Adrenals, and Hormonal Sabotage

2.9.1 The Cortisol–Progesterone Tug of War

Women with irregular light exposure, shift work, or disrupted Beyond estradiol and progesterone, one of the most disruptive forces acting on hormonal balance is chronic stress. The biochemical reality is this: progesterone and cortisol share a precursor—pregnenolone. Under prolonged stress, the body prioritizes cortisol production, diverting pregnenolone away from the luteal-phase progesterone surge critical for implantation and pregnancy maintenance.

This dynamic, often termed the “pregnenolone steal”, is not merely theoretical. Though not explicitly named in Mørch et al. (2025), the hormone timing findings align with a broader understanding that when adrenal hormones dominate, reproductive hormones suffer. High cortisol states have been associated with shortened luteal phases, disrupted ovulation, and lower endometrial receptivity.

Moreover, the physiological effects of stress extend beyond hormonal diversion. Chronic sympathetic activation affects pituitary signaling, thyroid conversion, insulin regulation, and circadian synchronization — all of which play a role in reproductive health. Fertility, in essence, is the first function the body sacrifices when survival is in question.

2.10 Lifestyle Interventions for Hormonal Realignment

2.10.1 Sleep, Light, and Circadian Alignment

Restoring hormonal harmony begins not in the pharmacy, but in the nervous system and the circadian rhythm. Wsleep often show elevated cortisol and dampened melatonin, both of which can impair the timing and amplitude of hormonal fluctuations.

Evidence from broader endocrinology (though not directly cited in your selected sources) shows that melatonin supports GnRH (gonadotropin-releasing hormone) pulsatility and enhances oocyte quality. Therefore, improving sleep hygiene, minimizing blue light exposure at night, and anchoring wake-up times become clinically significant fertility interventions.

2.10.2 Nutrition and Micronutrient Density

Revisiting Kapper (2024), the nutritional inputs to hormonal balance cannot be overstated. Many modern diets are deficient in:

- Magnesium — essential for progesterone synthesis

- Zinc — required for follicle maturation

- Iodine — supports estrogen detoxification and thyroid regulation

- Vitamin B6 — coenzyme for neurotransmitters that influence the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis

Correcting these deficits through whole-food nutrition or targeted supplementation can often normalize cycle length, improve cervical mucus production, and restore ovulation within 2–6 cycles, especially when combined with stress mitigation strategies.

2.11 Subclinical Hormonal Dysfunction: The Invisible Epidemic

2.11.1 When Labs Say “Normal” but the Body Doesn’t

A persistent challenge in diagnosing hormonal imbalance is that many women present with “normal” lab values—yet experience clear signs of dysfunction: irregular cycles, mid-luteal spotting, short luteal phases, mood swings, fatigue, infertility, or miscarriage.

This disconnect arises from a fundamental flaw in conventional testing: population reference ranges are often too broad and not optimized for reproductive function. For instance, progesterone levels of 5–20 ng/mL are considered “normal” in the luteal phase, but optimal implantation may require levels closer to 15–20 ng/mL, especially in older women or those with endometrial receptivity issues.

Jahromi et al. (2024) emphasize the timing-dependent outcomes of progesterone supplementation. Their meta-analysis suggests that synchrony—more than absolute level—determines success in embryo transfers. This principle applies equally to natural conception: many women’s hormone levels are not “low,” but mismatched to the cycle’s physiological demands.

2.12 Clinical Underdiagnosis and the Gendered Lens

2.12.1 When Women Are Told “It’s in Your Head”

Segarra (2023) rightly frames hormonal imbalance as both a medical and a sociocultural issue. Women’s symptoms—fatigue, irritability, anxiety, bloating, cycle changes—are often dismissed as stress, aging, or psychosomatic distress. But these are often the early indicators of hormonal dysfunction.

Medical systems often fail to validate these concerns unless they meet diagnostic thresholds like PCOS or premature ovarian failure. The result is a generation of women who are hormonally imbalanced but functionally invisible in the medical data. This fuels frustration, delayed treatment, and in many cases, unnecessary IVF when natural conception might have been achieved through endocrine restoration.

2.13 Reclaiming Hormonal Autonomy: A Public Health Imperative

2.13.1 Beyond Fertility — Toward Systemic Health

Hormones are not isolated to the reproductive system. Estradiol and progesterone influence cognitive function, cardiovascular resilience, bone density, immune modulation, and metabolic health. Fertility is merely the most visible symptom of a deeper equilibrium.

Thus, restoring hormonal balance is not just about getting pregnant—it’s about restoring health.

“Fertility is the canary in the coal mine for systemic wellness.”

—Paraphrased from Segarra (2023)

This shift in narrative—from fertility as a destination to fertility as a barometer of internal harmony—can liberate women from a reactive, interventionist model and place them back in the center of their own care.

2.14 Conclusion: The Case for a Hormonal Renaissance

The data are in, and they tell a compelling story: estradiol and progesterone are not just cycle regulators, but foundational health signals. When they are out of balance—whether through stress, exposure, timing, nutrient depletion, or clinical neglect—fertility falters. But the reversibility of this imbalance offers hope.

From Mørch et al. (2025)’s work on hormonal rhythm in embryo transfer, to Kapper’s (2024) elucidation of micronutrient cofactors, and Segarra’s (2023) political framing of hormonal autonomy—the imperative is clear. We must move beyond static lab values and embrace a systems biology model of hormonal care—one that listens to patterns, honors timing, and empowers women with science and sovereignty.

Infertility, in many cases, is not a mystery. It is a miscommunication between the body and the world it lives in. When that communication is restored—through nourishment, alignment, and awareness—conception becomes not just possible, but often inevitable.

Part 3: Nutrition for Conception — Foods That Heal

From leafy greens to omega-3s, the fertility diet explained.

Food is not just fuel; it is information. It speaks directly to your reproductive system, influencing hormone production, egg quality, endometrial receptivity, and long-term fecundity. But are you eating in a way that supports conception—or silently sabotaging it? This exposé unpacks the science behind fertility nutrition, bringing clarity to the crowded conversation around diets, supplements, and reproductive outcomes.

3.0 Introduction: Fertility Begins in the Gut, Not the Clinic

Long before ovulation, before embryo transfer, before the two-week wait—fertility begins at the cellular level, and nutrition is its primary architect. The oocyte (egg cell) takes over three months to mature, meaning every meal you eat today influences your fertility three menstrual cycles from now.

Yet nutritional care is rarely front and center in fertility protocols. Standard clinical models prioritize pharmaceutical stimulation and surgical retrieval, often relegating diet to afterthought. However, recent findings across clinical trials, meta-analyses, and mechanistic reviews suggest a powerful counter-narrative: the right nutrition can increase fertility outcomes, both natural and assisted, by double-digit margins (Skoracka, 2021; Farina, 2025).

3.1 The Fertility Diet: More Than Just “Healthy Eating”

3.1.1 Defining a Pro-Fertility Dietary Pattern

Alesi (2023) presents one of the most detailed syntheses of preconception dietary influence. Her findings converge around a few core principles:

- High intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes

- Low intake of trans fats, processed carbohydrates, and red meats

- Emphasis on unsaturated fats, particularly omega-3s

- Moderate, balanced protein consumption

This pattern reflects a modified Mediterranean diet, consistently shown to improve ovulation rates, menstrual regularity, and clinical pregnancy rates, especially in women with PCOS or endometriosis.

Crucially, this is not about calorie restriction or detox trends. The fertility diet is about micronutrient density, inflammation control, and hormonal modulation.

3.2 Omega-3 Fatty Acids: The Fertility Fat

3.2.1 Oocyte Health and Lipid Composition

The human egg is the largest cell in the body—and it is surrounded by a lipid-rich membrane. Omega-3 fatty acids, particularly DHA and EPA, are essential for membrane fluidity, mitochondrial function, and embryonic division post-fertilization.

Abodi (2022) found that higher dietary omega-3 intake was significantly correlated with better oocyte maturity and morphology, particularly in women undergoing IVF. Similarly, Trop-Steinberg (2024) concludes that dietary and supplemental omega-3s are positively associated with shorter time to pregnancy, especially in women over 35.

The mechanism? Omega-3s reduce systemic inflammation, enhance follicular vascularization, and support hormone receptor sensitivity—all crucial in both natural and assisted reproduction contexts.

3.3 Micronutrients and Their Fertility Mechanisms

3.3.1 The Hidden Deficiencies Behind Hormonal Disruption

Pandey (2024) outlines a comprehensive list of micronutrients with direct impacts on reproductive function:

- Folate: Supports oocyte development and prevents neural tube defects

- Vitamin D: Regulates AMH levels and ovulatory function

- Zinc: Involved in folliculogenesis and progesterone synthesis

- Magnesium: Critical for progesterone binding and stress modulation

- Iodine: Necessary for thyroid regulation, which underpins menstrual regularity

Most notably, Pandey points out that subclinical deficiencies are rampant—even in women eating “well”—due to soil depletion, food processing, and gastrointestinal malabsorption. This creates a paradox where women may be well-fed but undernourished at the reproductive level.

3.4 Gut Health as the Fertility Gateway

3.4.1 Absorption, Inflammation, and Hormone Regulation

The connection between the gut microbiome and fertility is increasingly evident. Gut flora influence estrogen metabolism, nutrient absorption, and immune tolerance—all of which affect ovulation and implantation.

Skoracka (2021) emphasizes that chronic gut inflammation or dysbiosis can reduce the bioavailability of key fertility nutrients, even when diet appears adequate. She also links high-refined sugar diets to elevated insulin levels, which contribute to estrogen dominance, anovulation, and endometrial inflammation.

Restoring fertility, therefore, involves more than “eating right”—it involves repairing the intestinal environment that governs nutrient use and hormonal feedback.

3.5 Nutraceuticals: Functional Foods with Fertility Potential

3.5.1 Beyond Pills — Food as Medicine

Farina (2025) explores how specific foods and botanicals possess nutraceutical properties—that is, food-based compounds that exert pharmacological effects. Key examples include:

- Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10): Enhances mitochondrial activity in aging oocytes

- Inositol: Improves insulin sensitivity and ovarian function in PCOS

- Curcumin: Reduces systemic inflammation and supports luteal function

- Resveratrol: Protects ovarian reserve and may improve embryo quality

Unlike isolated vitamin supplements, nutraceuticals often act synergistically, working across metabolic and hormonal pathways to enhance egg quality, reduce oxidative stress, and restore endocrine rhythm.

3.6 Nutrition and IVF Outcomes

3.6.1 What the Evidence Says About Supplements and ART

Hart (2024), in a rigorous review published in RBMO, analyzed the impact of preconception supplementation on IVF outcomes. Her findings?

- Women who took targeted supplements (including omega-3s, antioxidants, and micronutrients) had higher fertilization rates, improved embryo morphology, and increased live birth rates compared to controls.

- Timing mattered: the three months before retrieval appeared to be the most critical window.

- Excessive or poorly formulated supplements had no benefit or potentially negative effects, reinforcing the importance of evidence-based formulation and clinician oversight.

Hart’s study reinforces a shift in assisted reproductive care—from reactive hormone therapy to nutrient-supported folliculogenesis.

3.7 The Anti-Fertility Diet: What to Avoid

3.7.1 Foods That Undermine Reproductive Health

While much attention is given to what boosts fertility, it’s equally critical to examine what undermines it. Skoracka (2021) and Alesi (2023) both identify several food categories with negative impacts:

- Trans fats and hydrogenated oils: Linked to ovulatory infertility

- Refined sugars: Disrupt insulin and estrogen metabolism

- Excess animal protein: May reduce ovulatory function if unbalanced

- Alcohol and caffeine: Associated with delayed conception at high intakes

- Ultra-processed foods: Linked to hormonal disruption and gut dysbiosis

Women trying to conceive are not just feeding their bodies—they’re fueling their endocrine systems, their immune tolerance, and the next generation’s genetic start.

3.8 Clinical Challenges: Nutrition Still Under-Prescribed

3.8.1 The Blind Spot in Fertility Medicine

Despite a wealth of evidence, dietary interventions remain grossly underutilized in fertility care. Farina (2025) critiques the “drug-first” model that characterizes most reproductive medicine, noting that nutritional interventions are rarely reimbursed, under-taught in medical schools, and often delegated to generalist advice or apps.

This lack of integration results in lost opportunities—where egg quality could be improved, endometrial receptivity optimized, and IVF cycles made more effective with non-invasive, low-cost tools.

The problem is not lack of data—it is lack of systems to implement it.

3.9 Conclusion: Fertility Nutrition Is Fertility Medicine

The oocyte is not a passive cell. It is an active participant in its own destiny, responding to signals from hormones, nutrients, oxidative load, and inflammatory cues. What a woman eats, absorbs, and avoids in the 90 days before ovulation directly shapes the quality of that egg—and by extension, the trajectory of her fertility.

As the evidence from Skoracka (2021), Alesi (2023), Farina (2025), and others shows, nutrition is not complementary—it is foundational. It is also empowering: unlike genetics or age, diet is a variable women can change, optimize, and personalize.

If we are serious about supporting fertility—naturally or with assisted help—then we must begin with food. Not as folklore. Not as an afterthought. But as the first intervention.

Read also: Twin Flames of Afrobeats: The World Still Wants P-Square

Part 4: Weight, Exercise, and Reproductive Health

Why body balance is critical for ovulation and conception.

Fertility is not just about hormones or ovaries—it’s about energy, metabolism, and how the body perceives safety. Weight and exercise play a dual role: they can restore ovulation or disrupt it. In this exposé, we interrogate the science behind BMI, body composition, and movement, asking: when does the body feel ready to conceive?

4.0 Introduction: Reproduction as a Metabolic Luxury

From an evolutionary lens, fertility is not a biological constant—it is a conditional privilege, activated only when the body deems it safe. Metabolic stress, excess adiposity, and extreme leanness can all send the same signal: now is not the time.

As Caldwell (2024) writes, “the reproductive system is exquisitely sensitive to metabolic cues.” This means that both obesity and underweight states disrupt ovulation, implantation, and hormonal harmony. But the answer isn’t always weight loss or intense workouts. The real solution lies in metabolic equilibrium, not extremes.

4.1 The Weight-Fertility Paradox

4.1.1 Both High and Low BMI Impair Conception

Numerous studies confirm that fertility declines at both ends of the BMI spectrum. Jeong et al. (2024), in a meta-analysis of overweight women undergoing IVF, found that preconception weight loss significantly improved live birth rates—but only when achieved through sustainable, moderate interventions.

Conversely, women with very low BMI often experience hypothalamic amenorrhea, where the body suppresses ovulation due to insufficient energy availability. The critical takeaway: the body requires a minimum and maximum metabolic threshold for optimal reproductive function.

4.2 Exercise: Fertility Friend or Foe?

4.2.1 The Intensity Inflection Point

Maher (2024), in Public Health Review, underscores a U-shaped curve between physical activity and fertility. Moderate exercise is associated with improved ovulation, reduced insulin resistance, and healthier endometrial function. But excessive or intense endurance training, especially when combined with low energy intake, can suppress the HPO axis, leading to delayed or absent ovulation.

This is echoed by Zhang (2024), who highlights that more is not always better. Women engaging in high volumes of cardiovascular exercise (>5 hours/week) had lower conception rates unless their caloric intake matched energy output.

4.3 Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): Where Weight and Exercise Collide

4.3.1 Lifestyle as a First-Line Therapy

Donato (2025) emphasizes that lifestyle intervention is the cornerstone of PCOS treatment, especially in overweight or insulin-resistant phenotypes. Modest weight loss (5–10%) has been shown to restore ovulation, improve insulin sensitivity, and increase spontaneous pregnancy rates.

Gitsi et al. (2024), in Frontiers in Endocrinology, demonstrate that combined dietary and physical activity protocols outperform either alone in restoring fertility in obese women with PCOS. The interventions that worked best were not extreme—but consistent, including:

- 30–45 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity

- A Mediterranean-style, low-GI dietary pattern

- Targeted supplementation (e.g., myo-inositol, omega-3s)

These findings underscore a larger truth: metabolic inflammation, not just body fat, is the primary reproductive barrier in PCOS.

4.4 Adipose Tissue as an Endocrine Organ

4.4.1 How Fat Talks to the Ovary

Fat tissue is not inert—it’s biologically active. It secretes adipokines (like leptin, resistin, and adiponectin) that modulate gonadotropin signaling, insulin sensitivity, and estrogen conversion.

Mussawar et al. (2023) describe how visceral fat in particular leads to chronic low-grade inflammation, elevating cytokines such as TNF-alpha and IL-6. These inflammatory mediators interfere with ovarian follicle development and disrupt estrogen-progesterone balance, decreasing endometrial receptivity.

Ironically, excess adiposity may also increase peripheral conversion of androgens to estrogens, leading to an estrogen-dominant state and anovulation.

4.5 Preconception Weight Loss: Evidence and Caution

4.5.1 How Much Is Enough—And When Is It Too Late?

Jeong et al. (2024) and Caldwell (2024) agree: modest weight loss (3–7% of total body weight) in women with obesity can improve IVF outcomes, spontaneous conception, and ovulatory function. However, crash diets or aggressive caloric restriction may do the opposite—inducing endocrine stress, impairing luteal phase support, and even lowering embryo quality.

Caldwell (2024) also notes a timing caveat: weight loss should be completed before ovarian stimulation begins, as rapid pre-cycle changes may destabilize hormone levels during treatment.

The consensus is clear—slow, targeted interventions outperform rapid fixes, particularly in the 3–6 months before conception attempts.

4.6 Lean PCOS and the Invisible Struggles

4.6.1 Why Not All Weight Loss Helps

PCOS is not exclusive to overweight women. Maher (2024) points out that up to 20–30% of PCOS cases are lean, yet experience the same ovulatory dysfunction and infertility. In these cases, excessive focus on weight loss may worsen symptoms by:

- Further suppressing estradiol

- Elevating cortisol

- Worsening menstrual irregularity

Lean PCOS often requires metabolic repair, not weight reduction, including stress management, strength training, anti-inflammatory nutrition, and targeted supplementation like inositols or N-acetylcysteine.

4.7 Movement as Medicine: The Exercise Prescription

4.7.1 What the Data Says About Type and Frequency

Zhang (2024) and Gitsi et al. (2024) converge on specific recommendations for exercise as a fertility intervention:

- Moderate aerobic activity: 3–5 days/week (e.g., brisk walking, swimming)

- Resistance training: 2–3 days/week (enhances insulin sensitivity and hormone balance)

- Yoga or Pilates: Reduces stress and cortisol, improves parasympathetic tone

Importantly, Mussawar et al. (2023) note that the consistency of movement, not its intensity, is the greatest predictor of benefit. Even walking 30 minutes a day can initiate favorable endocrine shifts.

4.8 Body Fat Distribution Matters More Than Weight Alone

4.8.1 Waist Circumference and Fertility

Total weight is a crude marker. Studies now emphasize waist-to-hip ratio and visceral fat levels as better predictors of fertility outcomes than BMI. Maher (2024) reports that women with abdominal adiposity had lower ovulatory function, even at normal BMI, due to insulin resistance and leptin dysregulation.

This suggests that targeting fat loss, especially around the midsection, may yield greater fertility improvements than generalized weight loss.

4.9 The Mind-Body Interface: How Movement Calms the Cycle

4.9.1 Cortisol, Endorphins, and HPO Axis Regulation

Exercise is not just metabolic—it is hormonal and neurological. Moderate physical activity releases endorphins, lowers cortisol, and improves hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis communication. This is particularly relevant in cases of stress-induced anovulation or irregular cycles.

Donato (2025) emphasizes that movement improves sleep quality, gut motility, and mood—all of which feed back into the reproductive system. The body, sensing safety and stability, is more likely to resume ovulation and optimize implantation conditions.

4.10 Conclusion: Toward Metabolic Fertility, Not Thinness

Weight and exercise are neither villains nor saviors—they are tools. The key lies in understanding what the body is signaling through weight, shape, and energy patterns.

Fertility is optimized not at a particular size, but at a particular state of balance—where leptin, insulin, cortisol, estradiol, and progesterone are aligned. As the literature from Maher (2024), Jeong et al. (2024), Zhang (2024), and Donato (2025) affirms, metabolic health is the new fertility frontier.

In this light, the path to conception is not paved with perfection, but with intelligent, compassionate, and individualized movement toward balance.

Part 5: Stress, Anxiety, and Their Fertility Toll

How the mind can block the womb — and ways to reset it.

The ovary does not exist in isolation. It listens to the brain. It obeys the nervous system. And it is silenced by stress. While fertility clinics continue to measure hormones and follicles, the most powerful reproductive regulator may still be overlooked: the mind-body connection. This exposé explores how stress and anxiety disrupt fertility, and how targeted mental health interventions can bring the body back into reproductive rhythm.

5.0 Introduction: The Missing Variable in Fertility Treatment

When women struggle to conceive, the first culprits examined are hormonal imbalances, structural abnormalities, or sperm parameters. Rarely does anyone ask: How are you coping?

Yet the data is increasingly conclusive—psychological stress is a physiological disruptor. It suppresses the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis, alters cortisol rhythms, impacts menstrual regularity, and worsens IVF outcomes (Chai, 2023; Saadedine, 2025).

In a world where 1 in 6 couples experience infertility (Gao, 2025), and 87% of women in fertility treatment report clinically significant anxiety, the omission of mental health support in reproductive care is not just negligent—it is biologically naïve.

5.1 Psychological Toll: The Numbers Behind the Silence

5.1.1 Anxiety and Depression in Infertile Women

Gao (2025), in a landmark clinical study, found that 87% of infertile women met the criteria for moderate to severe anxiety, and over 60% met criteria for depressive symptoms. The emotional impact was independent of age, duration of infertility, or socioeconomic status.

Khalesi (2024) compared male and female infertility patients and concluded that women report significantly higher levels of psychological distress, including guilt, worthlessness, and rumination—especially when cycles fail or miscarriages occur.

The data expose a double burden: women must cope not only with biological barriers but with a silent emotional epidemic that may, in turn, undermine their fertility further.

5.2 Stress Physiology: How the Brain Shuts Down Reproduction

5.2.1 Cortisol, GnRH Suppression, and Ovulatory Disruption

The stress-fertility link is not metaphorical—it’s molecular.

When the brain perceives chronic stress, the hypothalamus suppresses gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), halting the signal that initiates the reproductive cascade. This leads to reduced LH and FSH, blunted estradiol, and anovulation.

Chai (2023) showed that infertile women undergoing IVF who had elevated cortisol levels also had poorer embryo quality and lower implantation rates. Cortisol dysregulation, particularly flattened diurnal rhythms, was a biomarker for unresolved anxiety and HPA axis dysfunction.

Saadedine (2025) expands on this, framing stress as a “silent pandemic” with physiological fingerprints—including cycle irregularity, luteal phase defects, and poor endometrial receptivity. Her review argues that unaddressed psychological stress is often a root cause of idiopathic infertility.

5.3 Infertility and Identity: A Crisis of Selfhood

5.3.1 Emotional Trauma and Quality of Life

Infertility destabilizes identity. As Shi (2024) reports, women undergoing prolonged fertility treatment experience a loss of self-concept, compounded by social stigma and repeated disappointment. This leads to a deteriorating quality of life, which correlates with further physiological dysregulation—creating a feedback loop of stress and infertility.

Women often report:

- Isolation from peers

- Feelings of brokenness or failure

- Marital strain

- Sexual aversion or performance anxiety

Shi emphasizes that unless these psychological wounds are addressed, interventions like IVF may treat the symptom but not the root dysfunction.

5.4 The Biochemistry of Belief: Stress as a Behavioral Block

5.4.1 Health Habits as Mediators

Kim (2025) introduced a critical insight: stress does not affect fertility only through hormones, but also through behavioral inhibition. Stressed women are less likely to:

- Maintain sleep regularity

- Exercise consistently

- Adhere to anti-inflammatory diets

- Take prescribed supplements

- Attend follow-up care

Kim’s research found that health-promoting behaviors act as a mediating variable—reducing the impact of stress on hormonal and reproductive outcomes. Her findings advocate for lifestyle coaching and structured routines as part of fertility care.

5.5 Cognitive Reconstruction: A Science-Backed Intervention

5.5.1 Reframing the Narrative

Masoumi (2025), in a randomized clinical trial, implemented cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for infertile women and observed a significant reduction in perceived stress, alongside improvements in menstrual regularity and sexual function.

CBT focused on:

- Reframing negative thought patterns

- Reducing catastrophic thinking about infertility

- Promoting self-worth and body compassion

- De-coupling identity from fertility status

This psychological reconditioning produced not just emotional relief, but measurable biological improvements, supporting the concept that perception influences physiology.

5.6 Social Support: The Unsung Fertility Treatment

5.6.1 Why Isolation Is Reproductive Sabotage

Khalesi (2024) and Shi (2024) both underscore that lack of emotional support worsens infertility outcomes. Women without partner, peer, or therapeutic support experience higher levels of rumination, cortisol dysregulation, and decision fatigue.

Masoumi (2025) further demonstrated that women enrolled in peer support groups had significantly better IVF adherence, fewer cancelled cycles, and higher emotional resilience during treatment.

Creating space for emotional processing is not indulgent—it is biologically protective.

5.7 The Vicious Cycle: Infertility Stress → Stress-Induced Infertility

5.7.1 A Closed Loop Without Intervention

Saadedine (2025) warns of a recursive dynamic: the longer infertility persists, the more distress it causes. The more distress, the more the body downregulates reproductive function. Without intervention, couples may spiral into repeated failure, each attempt more physiologically compromised than the last.

This calls for early integration of stress assessment in fertility care—not as a supportive adjunct, but as a core diagnostic dimension. Tools like the Fertility Quality of Life (FertiQoL) scale and cortisol salivary rhythm panels can serve as preventive markers.

5.8 IVF and Emotional Burnout

5.8.1 Emotional Exhaustion Reduces IVF Success

Chai (2023) and Gao (2025) both highlight that psychological stress is one of the best predictors of IVF attrition. Many couples drop out not for financial or medical reasons—but because they are emotionally depleted.

Women undergoing multiple rounds report:

- Emotional numbness

- Loss of hope

- Reproductive trauma

- Clinical depression

This not only affects cycle continuation—it also correlates with poorer outcomes in those who persist, suggesting that emotional state may influence physiological receptivity to ART.

5.9 Toward Integrated Mind-Body Fertility Medicine

5.9.1 What Should Change in Practice

Based on the combined findings of Kim (2025), Masoumi (2025), Chai (2023), and Saadedine (2025), the future of fertility care must include:

- Routine psychological screening for all patients at intake

- On-site or virtual CBT therapy

- Mind-body programs (yoga, meditation, breathwork)

- Lifestyle coaching focused on stress-resilient routines

- Peer support communities (in-person or digital)

Just as bloodwork and ultrasounds track physical readiness, these tools must be used to track emotional readiness, regulate the nervous system, and restore the biochemical pathways to conception.

5.10 Conclusion: The Ovary Listens to the Mind

The endocrine system does not operate in isolation. The brain speaks to the ovary—through cortisol, neurotransmitters, and nervous system tone. Stress is not just a feeling; it is a fertility disruptor, acting through real, measurable pathways.

The evidence from Gao (2025), Chai (2023), Masoumi (2025), and Saadedine (2025) confirms: the uterus may be ready, the hormones balanced—but if the brain perceives threat, reproduction is paused.

This means the road to conception is not just physical. It is emotional. It is cognitive. And it begins with restoring safety, self-trust, and emotional regulation. Until then, no pill, protocol, or procedure can fully override the mind-body disconnect.

Part 6: The Role of Sleep in Reproductive Wellness

Deep rest as medicine for ovulation and hormonal repair.

Sleep is not just recovery—it’s a metabolic recalibration, a hormonal symphony, and a reproductive prerequisite. Yet millions of women attempting to conceive are unknowingly sabotaged by erratic schedules, blue light exposure, insomnia, or shift work. Fertility is sensitive to circadian cues, and sleep may be the most overlooked pillar in reproductive care. This exposé explores how—and why—rest might be the most underprescribed fertility treatment of all.

6.0 Introduction: Sleep as a Fertility Hormone

We tend to compartmentalize sleep as a mental health concern, not a reproductive one. But as research increasingly shows, sleep is endocrine regulation. It governs cortisol rhythms, melatonin output, insulin sensitivity, and ovarian hormone secretion—all of which are intimately tied to female fertility.

Li (2024) confirms in a sweeping systematic review that women with sleep disturbances have significantly higher rates of infertility—even when accounting for age, BMI, and medical history. Yet few fertility assessments ask about bedtime, duration, or quality of rest. This oversight is costing women time, energy, and in some cases, their only viable reproductive window.

6.1 Circadian Biology and the Female Reproductive Axis

6.1.1 How Sleep Talks to the Ovary

The hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis is the core communication highway of the female reproductive system. It’s initiated by GnRH pulses, which are themselves regulated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN)—the brain’s master clock, located in the hypothalamus.

Disruption to circadian timing—such as erratic sleep/wake cycles, late-night light exposure, or shift work—can alter:

- LH surge timing

- Ovulation predictability

- Progesterone secretion

- Menstrual cycle length

Liang (2022) found that women with later bedtimes and wake times had higher reported rates of infertility, even after adjusting for socioeconomic and lifestyle factors. Circadian misalignment appears to not only delay conception—but also degrade reproductive integrity at a systemic level.

6.2 Time-to-Pregnancy and Sleep Disruption

6.2.1 Sleep Duration, Timing, and Conception Probability

How long—and when—you sleep directly influences fecundability (the probability of achieving pregnancy in a given menstrual cycle).

Zhang (2025), analyzing over 4,000 women, found that both short sleep (<6 hours) and long sleep (>9 hours) were associated with longer time-to-pregnancy. Optimal fecundability was observed in women sleeping 7–8 hours nightly, with consistent bedtime-waketime cycles.

Zhao (2025) takes this further, showing that sleep variability—defined as changes in bedtime/wake time of more than 90 minutes over a week—was strongly correlated with delayed conception, even in women with otherwise normal cycles. Sleep inconsistency, not just sleep deprivation, appears to disturb the hormonal cadence required for fertilization and implantation.

6.3 Ovarian Reserve and Sleep Quality

6.3.1 Poor Sleep, Poor Eggs

Lin (2025), in Fertility and Sterility, presents one of the most alarming correlations: poor sleep quality is associated with diminished ovarian reserve (DOR), as measured by antral follicle count (AFC) and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels. Even after controlling for age, women with chronic insomnia showed statistically lower AMH scores and reduced oocyte retrieval in IVF cycles.

Cai (2024), in a similar cohort of women undergoing infertility treatment, confirms these findings—highlighting that women with disturbed sleep had 23% fewer retrievable mature oocytes than their well-rested counterparts. The mechanism is believed to involve increased oxidative stress, altered melatonin secretion, and disruption of mitochondrial efficiency in granulosa cells surrounding the oocyte.

Ovarian health, long thought to be an age-dominant equation, is now understood to be heavily influenced by restorative sleep.

6.4 Sleep and Idiopathic Infertility: Filling in the Blanks

6.4.1 When Lab Results Look Normal—but the Body Isn’t

Caetano (2025) conducted a case-control study on 360 women with idiopathic infertility—those whose lab work and cycle tracking showed no obvious abnormalities. He found that this group was significantly more likely to:

- Report poor sleep quality

- Display extreme chronotypes (either early birds or night owls)

- Experience social jet lag (weekend vs. weekday sleep inconsistency)

The implication? Unexplained infertility may be partially explained by sleep dysfunction, a variable almost never included in traditional reproductive assessments.

“Sleep pattern dysregulation should be considered a modifiable risk factor in all infertility evaluations.”

—Caetano (2025)

6.5 Melatonin: The Fertility Molecule You’re Not Measuring

6.5.1 Nighttime Darkness and Reproductive Resilience

Melatonin, produced by the pineal gland in response to darkness, is often overlooked in fertility care. Yet it is a potent antioxidant concentrated in the ovarian follicle, where it:

- Reduces oxidative damage to the oocyte

- Enhances mitochondrial function

- sensitivity

Regulates LH surge Poor or inconsistent sleep reduces melatonin production, particularly in those exposed to blue light from phones, TVs, or computers at night.

Liang (2022) and Cai (2024) both suggest that restoring circadian melatonin patterns may improve egg quality and luteal phase function. Melatonin supplementation has even shown modest success in IVF cycles, though its long-term safety profile is still under investigation.

6.6 Sleep and IVF Outcomes: The Overlooked Variable

6.6.1 Bedtime Predicts Biochemical Pregnancy?

In clinical contexts, sleep is rarely tracked in IVF protocols. Yet emerging data suggest it should be.

Li (2024), in her systematic review, found that women with poor sleep (by PSQI index) had:

- Lower fertilization rates

- Poorer blastocyst morphology

- Higher cancellation and dropout rates

- Lower clinical pregnancy success

Zhao (2025) reinforces that women with erratic sleep during IVF preparation had a 17% lower likelihood of biochemical pregnancy, even when embryo quality was controlled. The circadian system, it seems, is an unrecognized co-pilot in fertility treatment.

6.7 Hormones in Sleep and Fertility: The Nighttime Symphony

6.7.1 Estrogen, Progesterone, and Cortisol: A Circadian Dance

Sleep is not passive; it is endocrine orchestration. At night, several key hormones that support fertility are released, rebalanced, or recalibrated. The most critical include:

- Progesterone, which rises after ovulation and promotes deep sleep by acting on GABA receptors.

- Estrogen, which regulates REM cycles and thermoregulation.

- Cortisol, which should decline through the evening, reaching its nadir during deep sleep.

When sleep is fragmented or misaligned, these hormones fall out of sync. Liang (2022) demonstrates that women with inconsistent bedtimes experience irregular cortisol slopes, which in turn disrupt estrogen and progesterone timing, delaying ovulation and shortening the luteal phase.

Cai (2024) also links poor sleep to elevated nighttime cortisol, which blunts the rise of progesterone post-ovulation—potentially compromising implantation success even in women with otherwise healthy ovarian markers.

6.8 Chronotype, Shift Work, and Reproductive Risk

6.8.1 Being a Night Owl Comes with a Fertility Cost

Not all sleep issues stem from insomnia. For many women, their natural biological preference for late nights—or their job demands—places them in permanent circadian conflict.

Caetano (2025) found that evening chronotypes (those who naturally sleep late and wake late) had significantly reduced fertility rates, independent of total sleep duration. Similarly, shift workers—especially those with rotating night shifts—face increased infertility diagnoses and reduced IVF success.

The mechanisms are clear:

- Light-at-night suppresses melatonin

- Irregular sleep-wake patterns desynchronize the HPO axis

- Social jet lag increases inflammation and insulin resistance

- Mood dysregulation is more common in night chronotypes, compounding stress-related infertility factors

Sleep timing, not just quantity, matters—perhaps even more than we’ve realized.

6.9 Intervening with Sleep: Practical Tools for Reproductive Recovery

6.9.1 Sleep Hygiene as a Fertility Protocol

The evidence now demands a new standard of care: sleep must be a structured component of fertility support. Fortunately, targeted interventions have shown promise.

Zhang (2025) and Zhao (2025) both advocate for preconception sleep optimization programs, especially during IVF cycles or natural conception attempts. Core recommendations include:

- Consistent bedtime and wake time (±30 minutes)

- Elimination of blue light 1–2 hours before sleep

- Sleeping in full darkness to preserve melatonin

- Temperature regulation (cooler bedrooms promote deep sleep)

- Mind-body techniques (e.g., yoga nidra, breathwork) to reduce cortisol before bed

Melatonin supplementation (1–3 mg) has also been explored, particularly in women over 35 or with poor oocyte quality. While not suitable for everyone, Cai (2024) reports that short-term use may improve oocyte mitochondrial efficiency and support luteal phase stability.

6.10 Tracking Sleep in Fertility Diagnostics

6.10.1 The Case for Including Sleep in Fertility Screening

Despite growing evidence, few reproductive specialists currently assess sleep in patient intakes. This gap is a missed opportunity.

Li (2024) suggests that every fertility evaluation should include:

- Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scoring

- Chronotype assessment (e.g., MEQ questionnaire)

- Sleep diaries for at least one full cycle

- Wearable device data (optional but increasingly accurate)

Zhao (2025) recommends combining sleep pattern analysis with menstrual tracking, allowing clinicians to identify correlations between disrupted nights and luteal phase defects, anovulation, or delayed implantation.

This approach would not only identify hidden risk factors—it could also reduce unexplained infertility diagnoses, giving women non-invasive, behavioral pathways to optimize their cycles.

6.11 Toward a Sleep-Inclusive Fertility Framework

6.11.1 From Reproductive Fragmentation to Systemic Healing

The traditional fertility model has too often focused narrowly on hormone levels, anatomy, or lab values—missing the broader systems biology of conception. Sleep is not separate from reproductive health—it regulates it.

From the melatonin-rich follicular microenvironment to the cortisol-calmed luteal window, the science is clear: poor sleep compromises fertility, while optimized sleep supports it across the entire cycle.

As Lin (2025) and Cai (2024) have shown, even in women with diminished ovarian reserve or age-related decline, restorative sleep may improve outcomes in ways pharmaceuticals cannot replicate.

The new frontier in reproductive medicine may not be another hormone or egg-freezing protocol—it may be in helping women sleep well, consistently, and deeply.

6.12 Conclusion: Rest as Reproductive Strategy

The modern woman is often told that her fertility is failing because of age, genes, or stress—but rarely because of sleep. And yet, as we’ve uncovered across this investigation, inadequate or misaligned sleep is one of the strongest modifiable risk factors for infertility.

Whether it’s poor ovarian response, luteal phase defects, failed implantation, or extended time-to-pregnancy, sleep emerges as a silent disruptor—and a powerful healer.

From Li (2024)’s review to Zhao (2025)’s sleep variability model, the message is clear: when the body sleeps, it restores; when it doesn’t, it withholds reproduction.

It’s time for clinicians, patients, and health systems alike to acknowledge what the science has made undeniable: you can’t ovulate, implant, or sustain a pregnancy without sleep—and maybe, you shouldn’t even try.

Part 7: Environmental Toxins and Hidden Infertility Triggers

Plastics, chemicals, and everyday toxins that disrupt fertility

The average woman is exposed to more than 100 synthetic chemicals before breakfast—through toothpaste, packaging, tap water, cosmetics, and household air. Most are untested for reproductive safety. As fertility rates quietly fall worldwide, the role of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) is no longer speculative—it is a public health emergency. This exposé traces the evidence from ovarian follicles to fetal epigenetics, uncovering how modern environments are interfering with the most ancient of biological processes: conception.

7.0 Introduction: Fertility in a Toxic World

Declining fertility rates are often attributed to age, lifestyle, or genetics. But a growing body of research suggests another culprit hiding in plain sight: toxic environmental exposures.

Hassan et al. (2024) outline a clear link between everyday contact with endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) and measurable dysfunction in ovulation, hormone synthesis, and ovarian reserve. These substances include:

- Phthalates from plastics and fragrances

- Bisphenols (like BPA) from food containers and receipts

- Parabens and triclosan in personal care products

- Pesticides and herbicides from non-organic produce

- Flame retardants, PFAS, and solvents from furniture and clothing

And disturbingly, many of these chemicals now show up in follicular fluid, amniotic sacs, breast milk, and placental tissue.

7.1 What Are Endocrine Disruptors—and Why Should We Care?

7.1.1 Chemical Mimics That Confuse the Body

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals are substances that interfere with the body’s natural hormone signaling. They can:

- Mimic estrogen or block progesterone

- Alter receptor sensitivity

- Disrupt hormone synthesis or metabolism

- Induce epigenetic changes that may be passed to offspring

Wang and Zhao (2024) explain that even small concentrations of EDCs can induce reproductive changes because hormonal pathways operate in nanomolar concentrations—making the endocrine system exquisitely vulnerable to synthetic interference.

Tricotteaux-Zarqaoui et al. (2024) call this an “epigenetic cascade,” where EDC exposure not only reduces fertility but may also alter embryonic gene expression, increase miscarriage risk, and contribute to reproductive cancers later in life.

7.2 Microplastics in the Ovary: New Evidence, Alarming Implications

7.2.1 From Bottles to Follicles

In a landmark 2025 study, Montano et al. provided the first direct evidence of microplastics in human ovarian follicular fluid. Using electron microscopy, researchers identified particles from polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polystyrene (PS)—common components of water bottles, food wrappers, and clothing—in the biological fluid surrounding developing eggs.

The implications are chilling. Microplastics:

- Trigger oxidative stress in the ovary

- Disrupt folliculogenesis and oocyte maturation

- May alter mitochondrial function and genetic stability in the egg itself

This means fertility decline may not only be functional—it may be physically embedded in the reproductive microenvironment.

“The presence of microplastics in ovarian follicles is not theoretical. It is now an observable reality.”

—Montano et al. (2025)

7.3 Personal Care Products: A Hidden Source of Hormonal Confusion

7.3.1 What’s in Your Beauty Bag Matters

Most women unknowingly apply dozens of endocrine disruptors to their skin every day. From moisturizers and shampoos to deodorants and cosmetics, phthalates, parabens, triclosan, oxybenzone, and benzophenones are pervasive—and poorly regulated.

Nataraj et al. (2025) detail how these chemicals can be absorbed dermally and bioaccumulate in fatty tissues, including the breast and ovaries. Their effects include:

- Decreased estradiol and AMH levels

- Increased risk of anovulation

- Menstrual irregularities

- Endometrial dysfunction

This exposure is particularly concerning during the periconception period, when hormonal orchestration is most critical.

7.4 Phthalates and Bisphenols: The Fertility Saboteurs

7.4.1 What the Data Really Shows

Blaauwendraad et al. (2025) investigated periconception concentrations of bisphenols and phthalates in 300 women undergoing fertility treatment. They found:

- Higher phthalate levels were linked to lower oocyte yield and poor embryo morphology

- Bisphenol A (BPA) concentrations correlated with lower clinical pregnancy rates and increased miscarriage risk

- Women in the top quartile of exposure had 30% lower fecundity rates

Importantly, these chemicals were not exotic or industrial—they were found in perfumes, canned foods, take-out containers, nail polish, and vinyl flooring. The study concludes that even in countries with partial bans, exposure remains dangerously high.

7.5 Epigenetics and the Multi-Generational Impact

7.5.1 Not Just Your Fertility—Your Child’s, Too

Tricotteaux-Zarqaoui et al. (2024) explore the heritable epigenetic risks of EDC exposure. Their research reveals that chemicals like BPA, dioxins, and PCBs can:

- Alter DNA methylation patterns in oocytes

- Impair placental vascularization

- Influence fetal gene expression linked to endocrine and immune function

- Possibly affect the reproductive capacity of future generations

In animal models, in utero EDC exposure led to reduced fertility in female offspring, even when their own postnatal environment was clean. The body does not easily forget these insults—and may pass them on.

7.6 EDCs and “Unexplained Infertility”

7.6.1 Filling in the Diagnostic Gaps

One of the most insidious aspects of environmental toxins is their invisibility in standard fertility testing. Women with normal labs, regular cycles, and no anatomical abnormalities may still struggle with conception—and often receive the frustrating diagnosis of unexplained infertility.

Hassan et al. (2024) argue that many of these cases are toxicological in origin, with EDCs disrupting:

- Hormone receptor function

- Endometrial receptivity

- Implantation timing

- Oocyte quality at the mitochondrial level

In these contexts, IVF may bypass mechanical hurdles but cannot fully overcome the reproductive instability induced by environmental exposure.

7.7 Awareness and Public Health Failures

7.7.1 Women Are Not Being Warned

Okman and Yalçın (2024), in a cross-sectional survey, found that over 70% of pregnant women and new mothers were unaware of the term “endocrine disruptor”. Less than 30% knew which products contained them. Awareness was even lower among lower-income and minority groups.

This knowledge gap is not accidental—it reflects a regulatory failure. Most reproductive toxins in personal care, packaging, and cleaning products are not required to be labeled, and the U.S. has banned fewer than a dozen EDCs out of the over 85,000 registered chemicals.

Without transparency or public education, women cannot make informed choices to protect their fertility.

7.8 Clean Living Without Obsession: What You Can Actually Do

7.8.1 Realistic Detox for Fertility Protection

While the toxic landscape may seem overwhelming, researchers urge action without alarmism. As Montano et al. (2025) note, even partial reductions in exposure to known EDCs can significantly improve fertility markers over time.

Key real-world strategies include:

- Switching to glass or stainless-steel containers instead of plastic

- Avoiding microwave use of plastic (even “BPA-free” types)

- Choosing fragrance-free personal care products

- Using the EWG Skin Deep database to vet cosmetics

- Buying organic or low-pesticide produce, especially for the “Dirty Dozen”

- Ventilating indoor spaces to reduce flame retardants and off-gassing

Importantly, detox does not mean perfection. It means reducing your cumulative chemical burden, particularly during the preconception window, which epigenetic research suggests is a critical 90-day period for gamete maturation (Tricotteaux-Zarqaoui et al., 2024).

7.9 Environmental Medicine in Fertility Clinics: Still Missing

7.9.1 A Silent Blind Spot in Reproductive Care

Despite mounting evidence, most reproductive endocrinologists and gynecologists receive no formal training in environmental health. Hassan et al. (2024) and Wang and Zhao (2024) lament that toxicological risks are excluded from routine fertility assessments, even though:

- EDCs can impair IVF success

- They contribute to “unexplained infertility”

- They affect ovarian reserve and egg quality

- They can influence the long-term health of offspring

Few clinics ask about occupational exposure, home air quality, or personal care routines, and even fewer provide evidence-based resources for patients seeking guidance.

This creates a system where women may undergo multiple cycles of IVF without ever being told that something in their shampoo or pantry may be working against them.

7.10 Cultural and Regulatory Failure: A Global Public Health Crisis

7.10.1 The Silent War on Reproductive Autonomy

Okman and Yalçın (2024) frame the EDC epidemic as a failure of both public health and reproductive justice. Women cannot protect their fertility if:

- They don’t know what’s in their products

- They don’t understand the risks

- Regulatory agencies fail to act on known dangers

In the U.S., only 11 chemicals are banned from cosmetics. In the EU, over 1,300 are prohibited. Yet global supply chains blur those lines, and many women are exposed through imports, travel, and online purchases.

Tricotteaux-Zarqaoui et al. (2024) call for international harmonization of chemical safety standards, particularly for products used by reproductive-age women and children.

Until then, the burden of protection lies unfairly on the individual, rather than the systems that created the exposure.

7.11 Integration, Not Fear: A New Model of Reproductive Care

7.11.1 From Fragmentation to Holistic Awareness

The path forward is not paranoia—it is integration. Environmental assessments must become a standard part of fertility care, not an “alternative” add-on.

This includes:

- Screening for high-risk exposures (occupational, lifestyle, dietary)

- Providing detox education alongside hormone testing

- Training clinicians in toxicology and epigenetics

- Expanding access to clean products for underserved populations

- Including EDC education in public health and school curricula

Wang and Zhao (2024) propose interdisciplinary fertility teams, combining endocrinologists with environmental medicine specialists, integrative nutritionists, and toxicologists. The goal is not to scare—but to empower women with science and strategy.

7.12 Conclusion: From Silent Exposure to Informed Protection

Fertility is not just hormonal—it is environmental.

As Hassan et al. (2024), Montano et al. (2025), and Tricotteaux-Zarqaoui et al. (2024) show, endocrine disruptors are not fringe science. They are inside us: in our follicles, our cycles, our placentas. Their fingerprints are on our rising infertility rates, our IVF failures, and perhaps even the developmental health of our children.

But the future is not fixed. Reducing toxic exposure—through smarter choices, better policies, and integrated care—can restore not only reproductive health, but agency.

This exposé closes with a simple but urgent truth: what we touch, eat, and inhale is talking to our ovaries. It’s time we started listening.

Part 8: Herbal Remedies and Traditional Healing Paths

Ancient wisdom meeting modern science in fertility solutions

Long before the age of IVF and ovulation tracking apps, women turned to herbs, rituals, and traditional medicine to support conception. While modern medicine often views these approaches as peripheral, the research is now catching up. From adaptogens and uterine tonics to centuries-old Asian protocols, this exposé unpacks how herbal and traditional systems are making a scientifically grounded return to the fertility conversation.

8.0 Introduction: Ancient Practices, Modern Validation

In many cultures, infertility has long been treated through the lens of energetic imbalance, digestive weakness, or blocked meridians—concepts often dismissed in Western biomedicine. Yet today, randomized trials and meta-analyses increasingly show that herbal remedies and traditional healing modalities can improve fertility outcomes, regulate menstrual cycles, and even enhance the success of assisted reproductive technologies (ART).

Hyun (2024), in a sweeping systematic review, confirms that herbal interventions—when properly formulated—can positively affect ovulation, endometrial thickness, implantation rates, and live birth outcomes in subfertile women.

8.1 The Global Landscape of Herbal Fertility Medicine

8.1.1 East Meets West in Reproductive Care

Herbal fertility care is not a monolith. It spans continents and philosophies:

- Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) uses herbs to harmonize yin and yang, nourish blood, and warm the uterus

- Ayurveda focuses on balancing doshas, especially Vata, which governs reproductive motion

- Western herbalism leans on uterine tonics like raspberry leaf and hormonal modulators like vitex (chasteberry)

- African and Middle Eastern traditions often include fenugreek, black seed, and maca root for hormonal and libido support

Chang (2023) emphasizes that these traditions are increasingly being synthesized with Western diagnostics, creating a hybridized fertility care model that is both individualized and evidence-informed.

8.2 Scientific Evidence: What the Studies Say

8.2.1 Efficacy Across Conditions and Modalities

Lashari et al. (2024), in a PRISMA review covering 65 studies, found that herbal interventions improved conception rates across a variety of conditions, including:

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

- Luteal phase defect

- Anovulation

- Unexplained infertility

Notably, they reported improved mid-cycle estradiol levels, increased progesterone in the luteal phase, and enhanced endometrial receptivity in women taking formulations containing vitex, dong quai, and peony root.

Peng et al. (2025) conducted a meta-analysis on traditional East Asian medicine combined with ART and found that acupuncture and herbal regimens increased clinical pregnancy rates by 28% and live birth rates by 22% compared to ART alone.

8.3 Chinese Herbal Formulations: Precision by Pattern

8.3.1 Treating Root, Not Just Branch

Khan (2021) describes how TCM formulas are rarely used in isolation. Rather, they are tailored based on a patient’s pattern diagnosis, such as “Kidney Yang Deficiency” or “Liver Qi Stagnation.” Common formulations include:

- Ba Zhen Tang: for blood and qi deficiency

- Gui Shao Di Huang Wan: to support ovarian function

- Bu Shen Yang Xue: often used in IVF adjunct protocols

These formulations aim not just to trigger ovulation but to nourish reproductive essence—a concept loosely aligning with mitochondrial health, endometrial function, and hormonal feedback loops.

Jung et al. (2025), in a multicenter study across Korean clinics, found that individualized herbal prescriptions significantly improved menstrual regularity and pregnancy outcomes over a 6-month follow-up period, with no major adverse effects reported.

8.4 Herbal Safety and Drug Interactions

8.4.1 When Natural Doesn’t Mean Risk-Free

Friedman (2022) warns that while herbal remedies offer hope, they also carry risks—especially when self-prescribed or combined with fertility drugs. Concerns include:

- Liver enzyme elevation

- Interference with gonadotropins

- Delayed follicular development

- Inaccurate labeling and contamination

The most common culprits include black cohosh, dong quai, and unregulated proprietary blends. Friedman recommends working only with trained herbalists and disclosing all supplements to fertility clinicians to avoid unintended interactions—particularly in ART protocols.

8.5 The Role of Adaptogens and Uterine Tonics

8.5.1 Bridging Stress and Hormonal Recovery

Adaptogens are herbs that modulate stress response, particularly through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Chronic stress is known to suppress GnRH and ovulation, making adaptogens a valuable class of herbs for restoring hormonal rhythm.

Lashari et al. (2024) highlight key adaptogens used in fertility contexts:

- Ashwagandha: supports thyroid and cortisol balance

- Rhodiola rosea: improves mood and ovarian blood flow

- Schisandra: protects liver and hormonal metabolism