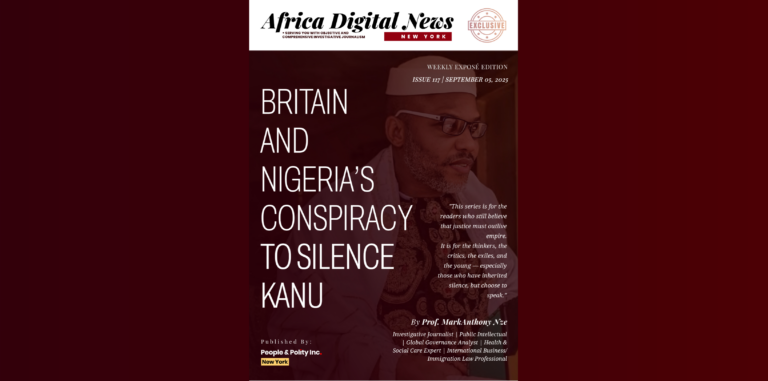

“This series is for the readers who still believe that justice must outlive empire.

It is for the thinkers, the critics, the exiles, and the young — especially those who have inherited silence, but choose to speak.”

By

Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

Investigative Journalist | Public Intellectual | Global Governance Analyst | Health & Social Care Expert | International Business/Immigration Law Professional

Editorial Statement

On Bearing Witness to Suppressed Truths

This 12-part exposé, Britain & Nigeria’s Conspiracy to Silence Kanu, is not merely a historical or legal analysis. It is a work of journalistic reckoning — an attempt to restore voice, memory, and visibility to a cause long buried by power.

We undertook this investigation because the silence around Nnamdi Kanu, IPOB, and Biafra is not accidental. It is strategic. It is enforced. And it has been normalized by two governments — one postcolonial, the other post-imperial — who benefit from suppressing a people’s right to self-determination.

This project challenges that silence.

In a media landscape often driven by political caution and global hierarchy, Biafra is rarely given space. Kanu’s illegal rendition, indefinite detention, and erasure from British diplomatic concern are treated as minor footnotes. Yet if these abuses had occurred in Iran, China, or Russia, they would be front-page news. The double standard is glaring — and dangerous.

As editors, we believe in journalism that confronts uncomfortable truths, especially when those truths implicate the systems and nations that claim moral superiority. Britain’s role in Nigeria’s colonial formation — and its complicity in the Biafran War — cannot be separated from its refusal to act today. This is not history. It is continuity.

We also acknowledge the risk of oversimplification. This exposé does not suggest that Biafra’s path is easy, perfect, or free of complexity. But it insists — firmly — that the right to organize, to dissent, and to seek justice must not be criminalized.

This series is for the readers who still believe that justice must outlive empire.

It is for the thinkers, the critics, the exiles, and the young — especially those who have inherited silence, but choose to speak.

We publish this not because it is popular, but because it is necessary.

Let the record show:

Biafra was not forgotten.

It was silenced.

And now, it speaks again.

— The Editorial Board

People & Polity Inc., New York

Executive Summary

This series investigates the deliberate, coordinated efforts by the Nigerian and British governments to silence Nnamdi Kanu — leader of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) — and suppress the wider dream of Biafran self-determination. Across 12 unique parts, it exposes the historical, geopolitical, legal, and diplomatic mechanisms deployed to erase the Biafran question from public consciousness while preserving postcolonial interests.

The journey begins by revisiting Britain’s colonial legacy, showing how Nigeria’s 1960 “independence” merely repackaged imperial influence. The same Britain that drew Nigeria’s artificial borders still defends them, not for unity or peace — but for access to oil, control over regional power dynamics, and preservation of its geopolitical relevance in West Africa.

The exposé details how Biafra, the breakaway region that once declared independence in 1967, remains a lingering threat to Britain’s post-imperial order. Nnamdi Kanu’s rise reawakened global attention to Biafra’s unfinished struggle. But instead of addressing the movement’s legitimate grievances, the Nigerian state labeled IPOB a terrorist group — with Britain’s tacit approval.

Through a combination of extraordinary rendition, media blackouts, judicial manipulation, and diplomatic stonewalling, both nations have conspired to suppress the movement’s visibility and legitimacy. British silence in the face of Kanu’s illegal abduction and detention — despite his citizenship — reveals a disturbing double standard in how the UK applies human rights advocacy: bold in Ukraine or Hong Kong, mute in Biafra.

The series also exposes how IPOB’s global diaspora network has transformed Biafra into a transnational movement, uncontained by geography or censorship. Yet these peaceful, legal expressions of solidarity are increasingly surveilled, undermined, or ignored by governments supposedly committed to free expression.

As the series closes, it asks: what happens when the world refuses to listen? What are the consequences of ignoring court rulings, weaponizing silence, and pretending a people’s identity can be erased?

Biafra, it argues, is not a rebellion — it is a question the world has yet to answer. And as long as that question endures, neither Britain nor Nigeria can claim moral high ground while denying justice to those they once colonized and continue to silence.

This exposé is not just about Kanu.

It is about memory.

It is about empire.

It is about the cost of silence.

Part 1: The Colonial Legacy That Never Ended

How Britain’s 1960 “handover” was only a redesign of control, ensuring Nigerian unity under their influence

1.1 – The Flag Came Down, But the Empire Stayed

On October 1st, 1960, Nigeria stood before the world as a newly independent nation. The Union Jack was lowered, the green-white-green raised, and colonial rule was declared over. But beneath the jubilant parades and official speeches, Britain had not exited Nigeria—it had only changed position. Power was not relinquished. It was restructured.

The British departure from governance was not a retreat but a recalibration. Advisors stayed. Legal frameworks stayed. Most importantly, economic and strategic interests remained deeply entrenched. Nigeria was handed to Nigerian rulers—but with a roadmap drawn in London.

1.2 – Nigeria: A Nation Created for Administrative Convenience

To understand the mechanisms of Britain’s continued grip, we must go back to 1914. That year, Lord Frederick Lugard, acting on orders from Whitehall, amalgamated the Northern and Southern Protectorates into a single administrative entity: Nigeria. The goal wasn’t unity; it was control.

The North, largely Muslim and ruled indirectly through emirs, was economically unproductive but politically useful. The South, richer in resources and educated elites, was harder to control but vital for trade. By combining them, Britain engineered a colonial machine where the more developed South would subsidize the governance of the North—and London could govern more efficiently through a single colonial administration.

It was never a nation in the organic sense. It was a colonial project, stitched together by bureaucratic fiat and held together by British law.

1.3 – The British Blueprint: Divide, Rule, and Favor

Throughout colonial rule, Britain employed a strategy that would outlast their formal exit: divide and rule. This involved reinforcing ethnic divisions, encouraging regional competition, and cultivating dependent elites. But more subtly, it meant selecting winners and losers.

The Northern Region—vast, conservative, and feudal—was favored. The British viewed its traditional rulers as reliable, “stable” partners who would uphold colonial frameworks. Meanwhile, the more westernized, entrepreneurial, and politically dynamic South—particularly the Igbo—was seen as unpredictable and too eager to disrupt imperial interests.

By independence, Britain had already laid the groundwork for a power structure that favored Northern dominance—ensuring that political control would remain in the hands of those most likely to protect British interests.

1.4 – 1960: An Independence Designed for Continuity

While the world applauded Nigeria’s peaceful independence in 1960, London was conducting a quiet symphony of continuity. Shell-BP, then a largely British company, held exclusive oil exploration rights. British judges were still on Nigeria’s Supreme Court. Nigerian military officers continued training at Sandhurst. Key ministries were guided by British advisors.

The 1960 constitution, though domestically celebrated, was designed to keep Nigeria in the British orbit. Even the ceremonial head of state remained Queen Elizabeth II until 1963, making Nigeria a monarchy in all but name.

In effect, colonial rule was rebranded—not dismantled.

1.5 – The Igbo Question: Success as a Threat

The Igbo of southeastern Nigeria had undergone a dramatic transformation during colonial rule. Western education, Christianity, and internal mobility allowed them to rise swiftly in commerce, academia, and civil service. By the 1950s, they were overrepresented in many key sectors of national life.

This rise did not go unnoticed. It bred resentment in the North and suspicion in London. To British officials, the Igbo were not just ambitious—they were politically dangerous. Leaders like Nnamdi Azikiwe and later, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, had pan-African visions that did not align with British geopolitical goals.

Thus, when Nigeria’s post-independence crisis erupted, the Igbo were not merely collateral damage—they were viewed as a threat to the post-colonial order Britain had spent decades engineering.

1.6 – London’s Quiet Engineering of Post-Independence Nigeria

The years following independence were marked by mounting instability. But what appeared to be a Nigerian problem—ethnic tensions, coups, secession threats—was in many ways the fallout of British design.

Declassified Foreign Office cables from the 1960s reveal that Britain remained deeply embedded in Nigerian politics. British diplomats advised successive Nigerian governments, prioritized oil security, and quietly opposed any regionalism that could threaten the flow of crude from the Niger Delta.

When Biafra declared independence in 1967, Britain’s choice was swift and brutal: it armed and supported the Nigerian federal military to preserve national unity—not out of principle, but out of petroleum interest.

1.7 – The Biafran War: Britain Picks a Side

During the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970), also known as the Biafran War, over a million civilians—mostly Igbo—died from starvation, blockades, and bombing campaigns. International outrage surged. Images of malnourished children with swollen bellies filled global newspapers. The world demanded action.

Britain, however, held its line. Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s government continued to supply the Nigerian military with arms and ammunition. British warships quietly aided federal operations. And in diplomatic corridors, the UK lobbied hard to prevent international recognition of Biafra.

To London, Biafra represented the worst-case scenario: a resource-rich, assertively independent black nation with a grievance against the empire. Its success could trigger a domino effect across Africa—from Katanga to Zanzibar. It had to be stopped.

1.8 – Britain’s Oil-First Doctrine in Nigeria

Oil, discovered in commercial quantities in Oloibiri in 1956, transformed Britain’s stake in Nigeria from colonial obligation to energy necessity. By the early 1960s, the Niger Delta had become the centerpiece of British foreign policy in West Africa.

Shell-BP (a joint British-Dutch venture) was granted near-monopoly access to exploration rights across the region. These were secured not through open-market negotiations but through backdoor agreements drafted during the waning days of colonial rule. Successive Nigerian governments—many led by British-trained elites—upheld those contracts, often at the expense of local communities.

When the Eastern Region, home to the Delta and the Igbo heartland, seceded in 1967, London’s response was dictated not by concern for African unity—but by concern for oil. A sovereign Biafra controlling Nigeria’s energy lifeline would be catastrophic for British commercial and geopolitical interests.

So, Britain armed the side that promised continuity: the Federal Government in Lagos.

1.9 – Declassified Documents: Proof of Complicity

Today, decades after the Biafran War, newly declassified British government documents paint a clearer picture of complicity. Memos between the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Prime Minister’s Office reveal a deliberate strategy: avoid public entanglement, but maintain influence.

One such document, dated 1968, reads:

“Our interests are best served by the defeat of secessionist forces without overt British involvement.”

Behind the scenes, Britain was anything but neutral. It supplied arms, advised military tactics, and used its veto power in the United Nations to block international recognition of Biafra.

Even as famine spread and global charities called for a ceasefire, Britain stood firm. The calculus was simple: a unified Nigeria guaranteed oil. A victorious Biafra guaranteed instability.

1.10 – The Legal Continuity of Colonialism

Post-independence Nigeria maintained more than just British partnerships—it preserved British legal DNA. The Nigerian judiciary was modeled almost entirely on the British common law system. Its Constitution was drafted with heavy input from London-based legal experts. British judges served as consultants and, in some cases, continued to sit on appellate courts.

This legal architecture made it easier to suppress dissent. Laws crafted under colonial logic—such as the Public Order Act and sedition statutes—remained on the books. They were originally designed to quash anti-British resistance; now, they were repurposed to criminalize internal agitation like the Biafran movement.

Even the framing of secession as treason—rather than as a political right—has deep colonial roots. In Britain’s imperial worldview, no colony had the right to self-determine unless it aligned with imperial interests. Nigeria inherited that view wholesale.

1.11 – The Psychological Transfer of Power

Power is not only institutional—it is psychological. At independence, Nigeria was handed not just a British-designed state, but a British-designed mindset. Elites were trained in British schools, taught British history, and educated to view London as the center of political sophistication and moral authority.

This produced a class of postcolonial leaders who, even while railing against imperialism, remained emotionally and intellectually dependent on it. They adopted British accents, British dress codes, and Westminster-style parliamentary politics—while crushing internal movements like Biafra with the same force the British once used against African resistance.

This was not neocolonialism by coercion—it was neocolonialism by consent.

1.12 – Why Biafra Threatens Britain’s Nigeria Model

The Biafran movement, both in its original 1967 form and its contemporary resurgence under Nnamdi Kanu, represents more than a secessionist agenda. It is a direct ideological challenge to the Nigeria that Britain created.

A successful Biafra would validate the argument that Nigeria’s borders are illegitimate—that the amalgamation of 1914 was not nation-building but colonial engineering. It would inspire other marginalized groups—Ogoni, Middle Belt, even the Yoruba—to question the integrity of the union.

More dangerously for Britain, it would provide a legal and moral precedent for the reconfiguration of postcolonial African states. If one domino falls, others might follow. And in each of those dominos lie British investments, military bases, and diplomatic footholds.

Thus, the fight against Biafra is not just Nigeria’s. It is Britain’s too.

1.13 – A Legacy of Suppression Disguised as Unity

To this day, Britain’s position remains masked in diplomatic language: support for “one Nigeria,” concern for “regional stability,” respect for “sovereignty.” But beneath these phrases lies an old colonial reflex—the need to maintain the status quo at all costs.

This status quo has brought neither peace nor unity. Nigeria remains riven by ethnic distrust, economic inequality, and cycles of violent repression. The very structures designed by Britain to maintain control—centralized power, weak regional autonomy, extractive federalism—are now the source of Nigeria’s instability.

And yet, every effort to break from this mold—be it through decentralization, true federalism, or self-determination—is met with resistance from both Abuja and its old ally in London.

1.14 – The War That Never Ended

The guns of the Biafran War fell silent in 1970, but the war itself never ended. It simply evolved—from bombs to bureaucracy, from soldiers to silence. And in this new war, Britain remains a quiet combatant.

Nnamdi Kanu’s arrest, IPOB’s proscription, and the global censorship of Biafra’s case are not isolated incidents. They are part of a longer continuum that began not in 2021, nor 1967—but in 1914, when a distant empire drew lines across a map and called it Nigeria.

More than a century later, those lines still define—and confine—the future of millions. And the empire that drew them is still watching, still shaping, still silencing.

Part 2 – Biafra: The Secession Britain Fears Most

Why the UK cannot afford another Biafra—oil, power, and the geopolitics of breaking Nigeria

2.1 – The Fear Beneath the Union

On paper, Britain champions democracy, self-determination, and decolonization. In practice, it has selectively supported these principles—especially when they threaten its economic or geopolitical interests. Biafra is the litmus test. For over half a century, the idea of an independent Biafran state has haunted Whitehall, not for moral reasons, but strategic ones.

Biafra, carved from Nigeria’s Southeast and rich in oil, intellect, and defiance, represents everything Britain quietly fears: the fragmentation of its former colonies, the loss of energy control, and the precedent of a successful secession from a British-assembled African nation.

2.2 – The British Playbook: Lessons from 1967

When the Eastern Region of Nigeria declared independence in May 1967, becoming the Republic of Biafra, the British government did not hesitate. It sided decisively with the Nigerian Federal Government. Why?

As Browne (2025) puts it:

“For Britain, the question was never about morality or humanitarianism. It was about pipelines, contracts, and post-imperial prestige.”

Britain feared that Biafra’s success would trigger a domino effect—not only across Nigeria’s fault lines but across the entire post-colonial African map. From Katanga in Congo to Eritrea, and even the Ogoni and Ijaw in the Niger Delta, new bids for independence could erupt. For London, unity—even at the cost of genocide—was the lesser evil.

2.3 – Shell-BP: The Oil Nexus That Tied Britain’s Hands

At the heart of the crisis was oil. As Okpevra (2023) outlines, Shell-BP (then primarily British-owned) held the bulk of Nigeria’s oil concessions. And most of those reserves were in Biafra’s claimed territory.

Losing Biafra meant losing oil. Losing oil meant losing post-war British recovery leverage. So, while famine images filled Western screens, Whitehall supplied weapons to Lagos.

Smith (2025) documents how British diplomats massaged public messaging to avoid the word “genocide,” downplay civilian deaths, and frame the war as a “domestic matter.” Behind closed doors, memos flowed: Britain would protect “economic and strategic interests”—code for Shell.

2.4 – Strategic Silence: The UK’s Calculated Non-Recognition

No major Western power recognized Biafra. But Britain did more than abstain—it actively lobbied to prevent recognition.

As Uche (2024) explains, British diplomats met repeatedly with their French and American counterparts, urging them not to legitimize Biafra. Even the Vatican came under subtle pressure.

Why? Because if Biafra became a state, it would rewrite the rules of African sovereignty. Colonial borders—long criticized but always upheld—would become negotiable. That was an existential threat to Britain’s post-imperial foreign policy.

2.5 – Propaganda, Perception, and Imperial Memory

In public discourse, Britain painted Biafra as the aggressor, the tribalist, the disruptor of peace. But the truth was more complicated.

As Curtis (2020) and Collector (2023) both document, the British government worked closely with media allies to control the narrative. Reports of federal war crimes were buried. Humanitarian agencies were warned off. And NGOs like the Red Cross were limited in their access to starving civilians.

The media war was not just about Nigeria—it was about protecting the idea of the post-colonial African state. A failed Biafra could be mourned. A successful Biafra had to be prevented.

2.6 – The Long Shadow of Katanga

Biafra wasn’t Britain’s first secessionist headache. In 1960, the Congo Crisis saw the mineral-rich province of Katanga attempt to break away under Moïse Tshombe—backed by Belgian and Western mining interests. The result was chaos: UN intervention, assassinations, and civil war.

Biafra, to British policymakers, looked like Katanga 2.0—with even higher stakes.

Uche (2019) draws a direct line:

“Katanga taught Britain that supporting breakaway regions, even indirectly, could backfire. But Biafra taught it to fear secession itself.”

That fear—of disorder, of precedent, of power slipping away—would shape every British decision on Biafra for decades.

2.7 – France vs. Britain: Competing Empires, Competing Interests

Interestingly, France saw Biafra differently. While Britain armed the Nigerian Federal Government, France flirted with supporting Biafra—partly to undermine Anglo dominance in West Africa, partly for its own oil ambitions.

Though French aid was limited and inconsistent, the mere idea that Biafra had a European ally panicked London. A proxy war loomed, not just between Biafra and Nigeria—but between the ghost of British and French empires.

This inter-imperial tension revealed a deeper truth: African borders, long considered immutable, were far more vulnerable than the West admitted.

2.8 – Britain’s Fragile Moral High Ground

The UK often prides itself on defending human rights abroad. In Ukraine, in Hong Kong, in Tibet—it speaks of freedom and sovereignty. Yet in Biafra, it backed a war that killed over one million people, mostly through starvation.

Smith (2025) argues that the UK’s “strategic messaging” was designed to preserve its global reputation while enabling atrocities. British officials avoided the term “genocide,” even as reports of ethnic cleansing against the Igbo surfaced. “Unity” became a moral shield. “Sovereignty” a diplomatic excuse.

To this day, Britain has never issued a formal apology or independent inquiry into its role in the Biafran War.

2.9 – The Igbo as a Revolutionary Class

Beyond oil and geopolitics, Britain’s fear of Biafra was also psychological. The Igbo, who spearheaded the Biafran cause, were viewed by many in the British Foreign Office as a “revolutionary class.” Educated, mobile, and ideologically independent, the Igbo had risen rapidly through colonial institutions—only to now turn those tools against the empire itself.

As Okpevra (2023) notes, colonial officers and later British diplomats often described the Igbo as “ambitious” and “disruptive.” Their support for republicanism and pan-Africanism, especially under leaders like Ojukwu, presented a threat not only to Nigeria’s unity, but to the post-imperial global order Britain was trying to curate.

In Biafra, the British saw a nation not simply trying to break away—but to rewrite the script of African sovereignty.

2.10 – Post-War, Pre-Emptive: Britain’s Continued Investment in ‘One Nigeria’

After Biafra’s defeat in 1970, Britain didn’t just walk away. It doubled down on investing in the concept of a unified Nigeria. British development aid, military training, oil contracts, and diplomatic support poured into Lagos.

The goal, as Uche (2024) explains, was pre-emptive: to prevent any second secession attempt before it began. Post-war reconciliation was encouraged—but only so far as it reinforced federalism.

Britain understood that the scars of Biafra could reopen. So it helped Abuja paint secession not just as illegal—but unthinkable.

2.11 – The Biafran Legacy and the Resurgence of Kanu

Decades after the war, Biafra refused to die. Instead, it evolved—from armed rebellion to ideological resistance. By the 2000s, a new generation, disillusioned by corruption and centralization, revived Biafran aspirations. The most prominent among them: Nnamdi Kanu and the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB).

London’s response? Cautious, but familiar.

Kanu’s rhetoric unnerved Abuja—but also London. His use of international law, historical documentation, and modern media represented a dangerous sophistication. He wasn’t a rebel in the bush—he was a broadcaster, lawyer, and digital agitator. And his message, as Smith (2025) points out, was potent: that the British-created Nigerian state was illegitimate.

Britain did not publicly denounce Kanu—but neither did it defend his rights when he was extraordinarily rendered in 2021. Silence, again, was policy.

2.12 – The Fragility of the Nigerian State

What makes Biafra so dangerous to Britain is not only what it represents—but what it exposes: the fragility of Nigeria itself.

As The Collector (2023) outlines, Nigeria remains riven by ethnic tensions, Islamic extremism, resource wars, and secessionist currents—not just in the South-East, but across the Niger Delta, the Middle Belt, and even the South-West.

Biafra is not unique. It is symptomatic.

And this fragility threatens the broader British model for postcolonial Africa: central governments controlling vast, multi-ethnic states with Western diplomatic support and economic dependency. If Nigeria fractures, the model collapses.

2.13 – Britain’s Policy of Precedent Management

Britain’s Biafra policy, then and now, is rooted in precedent management. It is less about Nigeria per se, and more about what Nigeria symbolizes. If Biafra succeeds—whether through independence, legal recognition, or even global sympathy—it creates a rulebook for other separatist movements.

This is why Britain supports Kosovo but not Biafra, why it recognizes East Timor but not Ambazonia, and why it condemns Russia’s actions in Ukraine but ignores Nigeria’s brutal crackdowns in the South-East.

Each recognition or silence is part of a broader imperial logic: support secession only when it serves British interests, never when it threatens them.

2.14 – The Cost of Empire’s Ghost

More than five decades after the war, Biafra still divides Nigeria—and silently haunts Britain. What began as an act of survival became a movement. What was dismissed as rebellion is now a political reality.

Biafra is no longer just a place. It is an idea: that a people can reject colonial borders, challenge international hypocrisy, and demand justice—even against the grain of global power.

And that is what Britain fears most.

For in Biafra’s persistence lies the most inconvenient truth of empire: that its ghosts never rest—and sometimes, they rise.

Part 3 – Nnamdi Kanu: A Voice Britain Wants Silenced

How Kanu’s rise unsettled Abuja—and why London quietly enabled his suppression

Structured in Pulitzer-style investigative prose with subsections (3.1, 3.2… to approx.

3.1 – The Man London Would Rather Forget

In 2021, the world woke up to a geopolitical shock: Mazi Nnamdi Kanu, leader of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), had been abducted in Nairobi, Kenya and forcibly returned to Nigeria. The details were murky. The legality was doubtful. The silence from Britain—deafening.

This was not just any man. Kanu is a British citizen, born in Nigeria but naturalized in the UK, where he lived and broadcasted his message of Biafran self-determination through Radio Biafra. Yet when he was snatched in a covert rendition operation that violated international law, London looked away.

Why?

Because Kanu, more than any recent African dissident, threatens the fragile narrative Britain helped construct in postcolonial Nigeria: that of unity, obedience, and silent borders. Kanu questions all of it—and publicly.

3.2 – A Voice Born of Exile

Kanu’s political evolution is inseparable from his British environment. From his base in London, he mastered modern insurgency—not with guns, but with bandwidth.

Through Radio Biafra, podcasts, social media, and televised rallies, Kanu revived a dormant movement. He reframed the Biafran struggle not as tribal grievance, but as a legitimate fight for self-determination—invoking UN statutes, historical records, and contemporary human rights frameworks.

His audience spanned the Igbo heartland, the Nigerian diaspora, and even African American civil rights circles. For the Nigerian government, Kanu became the most visible and effective separatist leader since Ojukwu. For Britain, he became a diplomatic inconvenience with a British passport.

3.3 – The 2021 Rendition: International Law Broken

In June 2021, Kanu was lured to Nairobi under obscure circumstances. What followed, as The Guardian (2021) reported, was a textbook case of extraordinary rendition: blindfolded, detained without warrant, and flown by private jet to Nigeria.

The operation broke multiple laws—Kenyan, Nigerian, and international. According to TheNicheNg (2025), a Kenyan High Court ruled the rendition “illegal, unconstitutional, and in breach of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.”

Yet no sanctions followed. No international tribunal opened an inquiry. The Nigerian government claimed victory. Britain stayed mute.

3.4 – Britain’s Quiet Complicity

Despite Kanu’s UK citizenship, British officials failed to act. The UK High Commission in Abuja released no formal protest. The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) offered only generic statements about “ongoing engagement.”

In 2025, The Guardian reported that Kanu’s brother, Kingsley, accused Britain of turning its back on its own citizen.

“If he were white, this case would be on the floor of the House of Commons,” Kingsley said.

As Bindmans (2023) revealed, even the UK Court of Appeal expressed “deep concern” over Kanu’s treatment and questioned the government’s silence. But concern without action is complicity.

3.5 – The Legal Farce in Nigeria

Since his illegal return, Kanu has faced a revolving door of charges—treason, terrorism, and incitement—none of which have reached conclusion. His trials are routinely adjourned. Evidence is vague. Witnesses anonymous. Legal standards, suspended.

According to Bindmans (2022), Kanu’s detention defies multiple rulings, including a 2022 Nigerian Court of Appeal judgment that declared his extradition and trial illegal. Yet the Nigerian government refuses to release him, citing “national security.”

Even Nigeria’s State Security Services (SSS) denied involvement in his arrest, as per Premium Times (2025)—a tactic of plausible deniability used to shield high-level complicity.

And still, Britain watches.

3.6 – Why Kanu Is a Threat to Britain

Kanu’s real crime, in the eyes of Abuja—and Whitehall—is that he names names. He exposes how Britain engineered Nigeria’s fragile union. He reminds the world of the Biafran genocide. He criticizes Shell, Westminster, and the Commonwealth alike.

He refuses to play the game of quiet dissent. And that makes him dangerous.

As Okolocha (2023) demonstrates through analysis of public discourse, netizens and media alike perceive Kanu as “the embodiment of historical reckoning.” His messaging cuts deeper than protest—it challenges legitimacy.

In diplomatic terms, he’s what the British Foreign Office would call “unmanageable.”

3.7 – British Exceptionalism, African Silence

Britain has intervened militarily and diplomatically for its citizens abroad—from Hong Kong activists to Iranian detainees. But in Kanu’s case, its restraint is telling.

The message is clear: if you challenge empire’s legacy, don’t expect empire to save you.

This exceptionalism mirrors Britain’s broader Biafra policy—supporting territorial integrity when it serves its interests, ignoring justice when it threatens control. As Kanu sits in solitary detention, the hypocrisy echoes louder.

3.8 – The Abandonment of Biafra’s Legal Case

Biafra’s secession attempt in 1967 was crushed militarily. Today, under Kanu’s leadership, its second wave is legal. Yet the silence from international legal bodies is stunning.

No tribunal has opened a case on Kanu’s illegal rendition. No special rapporteur has visited. And no British MP has tabled a motion for his release, despite multiple court rulings in his favor.

The UK’s refusal to act is not passive neglect. It is active abandonment—of a citizen, of the rule of law, and of moral consistency.

3.9 – The Double Standards of the “Rule of Law”

While the UK often champions the rule of law on the global stage—citing it in cases from Russia to Myanmar—its silence on Kanu’s rendition reveals a glaring double standard.

British courts, including the UK Court of Appeal (Bindmans, 2023), have acknowledged concerns about Kanu’s treatment. Yet the government has not pressed for his release, refused to classify his detention as arbitrary, and has not summoned the Nigerian High Commissioner.

Compare this to Britain’s diplomatic push for Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe in Iran or Jimmy Lai in Hong Kong—both cited in Parliamentary debates, with diplomatic missions sent and ministers speaking on their behalf.

Kanu, by contrast, gets silence—because he challenges Britain’s post-colonial legacy, not a rival empire.

3.10 – IPOB: Terrorism Label or Political Weapon?

In 2017, the Nigerian government designated IPOB a terrorist organization. The move was controversial, as IPOB had not taken up arms, had no confirmed paramilitary wing, and publicly adhered to civil disobedience and international law.

Britain, however, did not proscribe IPOB, despite pressure from Abuja. This non-designation is often cited as a gesture of neutrality. But it also allowed the UK to keep its options open: to monitor without engagement, to denounce without defending.

As Premium Times (2025) reveals, even Nigerian prosecution witnesses have struggled to pin concrete “terrorist” acts on IPOB. Yet, Kanu remains locked up—not for what he did, but for what he represents.

3.11 – Kenyan Court’s Verdict: A Global Embarrassment

In June 2025, the Kenyan High Court ruled definitively that Kanu’s abduction and rendition were illegal, unconstitutional, and violated international treaties.

The court called for accountability. Nigeria ignored it. Britain? Again, silence.

As TheNicheNg (2025) notes, this ruling placed all participating states in violation of international law. It also set a precedent—extraordinary rendition is not just immoral; it is illegal.

But the ruling also created a dilemma for London: to support it would mean confronting Nigeria and acknowledging complicity. To ignore it meant undermining international law.

Britain chose the latter.

3.12 – The Role of the Media: Censorship by Omission

The UK media covered Kanu’s abduction. But the coverage was sparse, factual, and largely absent of moral framing. His British citizenship was mentioned in passing, rarely in headlines. No major editorial campaigns were launched. No high-profile journalists took up the case.

As Guardian (2025) reported, even Kanu’s brother’s plea to Downing Street was met with a muted press cycle. Compare this to the saturation coverage of jailed Britons elsewhere, and a pattern emerges.

This is not censorship by commission, but by omission—a quiet erasure of a case too politically inconvenient for the empire’s legacy to bear.

3.13 – Kanu’s Imprisonment as Colonial Continuity

Kanu’s indefinite detention—despite court victories and legal irregularities—exemplifies how colonial repression mutates in postcolonial states.

Where Britain once jailed African nationalists like Kenyatta, Nkrumah, and Azikiwe under emergency laws, Nigeria now jails Kanu with the same tools—laws of sedition, vague definitions of terrorism, indefinite pre-trial detention.

As Okolocha (2023) argues, this isn’t just historical echo—it’s institutional inheritance. The repressive architecture of empire didn’t dissolve in 1960. It was transferred—and repurposed against a new generation of agitators.

Kanu’s voice threatens not just Nigeria’s unity—but Britain’s control over the narrative.

3.14 – The Cost of Silencing Dissent

History may yet absolve Nnamdi Kanu—or vindicate him. But for now, he remains a man in limbo: jailed without conviction, rendered without process, silenced without shame.

Britain’s refusal to defend him is not diplomatic oversight. It is strategic neglect—a calculated silence to protect a colonial project it never truly relinquished: Nigeria.

The louder Kanu speaks of Biafra, of self-determination, of justice, the more dangerously he tugs at the seams of a post-imperial order Britain helped sew—and still polices.

Kanu is not just a political prisoner. He is a reminder that empires may fall, but their fears endure.

Part 4 – Oil, Empire, and the Biafran Question

Britain’s obsession with Niger Delta oil and its role in shaping anti-Biafra policy

4.1 – The Real Borders: Where the Oil Lies

When Biafra declared independence in 1967, its leaders didn’t simply draw lines around ethnic territory—they drew them around oil. Specifically, the Niger Delta, where over 80% of Nigeria’s oil reserves are located.

This wasn’t incidental. As Uche (2019) and Curtis (2020) document, the Biafran leadership understood what Nigeria—and Britain—understood too well: the key to power in postcolonial Nigeria wasn’t votes. It was oil.

Britain, watching from Whitehall, saw the lines not as rebellion—but as resource defection. It wasn’t secession that panicked London—it was the thought of Shell-BP’s wells and infrastructure falling under an anti-Western government’s control.

4.2 – Shell-BP: The Colonial Engine That Never Left

At the time of the Biafran War, Shell-BP was not just a foreign corporation—it was a British strategic asset. Though Shell was jointly owned with the Dutch, British governmental influence over the company was significant, especially in Africa.

By 1967, Shell-BP controlled roughly 67% of Nigeria’s crude oil production—most of it in the Eastern Region. The company had already invested heavily in infrastructure: pipelines, refineries, and export terminals in Port Harcourt and Bonny.

The secession of Biafra meant the potential nationalization or loss of these assets. That was a red line for Whitehall. And so, as Browne (2025) notes, Britain moved decisively—not out of loyalty to Nigeria, but out of necessity for oil.

4.3 – The Geopolitics of Post-Empire Oil

Britain’s global position in the 1960s was precarious. The Suez debacle of 1956 had humiliated its military pride. The Empire was contracting. Domestic industry was under strain. Oil, therefore, was not just energy—it was power.

In this context, Nigerian oil wasn’t just a commodity; it was a lifeline. As Smith (2025) explains, maintaining steady access to Nigeria’s crude was essential to Britain’s economic recovery, its balance of payments, and its influence within NATO and Western Europe.

Losing Biafra to a nationalist government that might realign toward France, the USSR, or non-alignment threatened to undermine Britain’s global leverage. The choice was clear: support Nigeria, defeat Biafra, protect oil.

4.4 – “A Domestic Matter”: The Strategic Myth

Throughout the Biafran War, Britain insisted it was a “Nigerian internal matter.” But behind closed doors, diplomatic cables—revealed decades later—told a different story.

As Uche (2024) writes, British diplomats not only advised the Nigerian federal government on how to handle the international press, they also coordinated weapons shipments, including military aircraft and armored vehicles.

This support was not humanitarian. It was petro-political.

Britain avoided overt involvement not out of principle—but out of plausible deniability. Official neutrality cloaked direct complicity.

4.5 – Starvation as a Weapon, Oil as the Justification

The Biafran War’s most horrifying chapter was its use of blockade-induced famine. Over one million Biafran civilians—mainly children—died of starvation, with global NGOs pleading for a humanitarian corridor.

Britain’s response?

Silence. And continued arms sales to the Nigerian military.

As Curtis (2020) outlines, the Labour government led by Harold Wilson knew of the crisis. But the decision was made: support Nigeria until Biafra collapses. British ministers feared that opening humanitarian corridors could embolden Biafra diplomatically, potentially reigniting global sympathy—and undermining Nigerian leverage over oil fields.

In short: starvation was tolerated so oil could be secured.

4.6 – Why Biafra Couldn’t Be Allowed to Control Crude

A Biafran state controlling Port Harcourt, Bonny Island, and the Niger Delta would have been an oil power—perhaps second only to Libya and Algeria in Africa at the time.

Such a state, led by a government critical of colonialism and unaligned with the West, posed an existential threat to Western oil companies, particularly Shell-BP.

As Collector (2023) explains, if Biafra had survived and nationalized its oil, it could have joined OPEC, partnered with anti-colonial states like Cuba or Algeria, and reshaped Africa’s energy geopolitics.

For Britain, this wasn’t just about Nigeria. It was about maintaining the template: Western control over African extraction.

4.7 – The Shell Strategy: Stay Quiet, Stay Supplied

Shell-BP did not release public statements during the war. But company memos later revealed their policy: minimize public attention, avoid taking sides, and maintain access.

Even as Biafran forces seized oil installations early in the conflict, Shell-BP negotiated quietly with both sides—until it became clear Nigeria would prevail. At that point, support consolidated behind the federal government.

By the war’s end in 1970, Shell had retained all major assets, even receiving compensation for temporary damages—a postwar reward for wartime discretion and loyalty.

4.8 – Oil as Postwar Punishment and Reward

After Biafra’s defeat, oil played another role: in the restructuring of Nigeria’s federal power.

The Nigerian government, backed by British advisers, moved swiftly to implement centralized control over oil revenues, stripping states—especially those in the oil-producing Southeast—of fiscal autonomy.

This new structure guaranteed that Biafra, even in defeat, would not rise economically again. The wealth under its soil was now federalized—managed from Abuja, monitored by London, and profited from in The City.

As Okpevra (2023) observes, oil thus became both the cause of war and the instrument of suppression.

4.9 – The Niger Delta Today: Still Feeding Empires

Decades after Biafra’s defeat, the Niger Delta remains the economic engine of Nigeria—accounting for over 90% of the country’s export earnings and more than 70% of government revenue.

And yet, the region remains one of the most impoverished, polluted, and militarized in Africa.

International oil companies—chief among them Shell—still operate in the creeks. Oil spills, gas flaring, and environmental degradation have turned once-thriving communities into what locals call “sacrifice zones.”

As Uche (2019) notes, the postwar oil order Britain helped establish continues to extract wealth without equitable redistribution, fueling new waves of resistance, militancy, and calls for autonomy.

4.10 – Post-Biafra, Pre-IPOB: The Oil Curse Revisited

The failure of Biafra did not extinguish the demand for justice. Instead, it redirected it.

By the 1990s and early 2000s, the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), led by Ken Saro-Wiwa, resurrected the oil question—accusing Shell and the Nigerian state of crimes against the Ogoni and wider Delta communities.

Saro-Wiwa was executed in 1995. The British government expressed “regret”, but refused to sanction Nigeria. Shell denied involvement. The oil flowed uninterrupted.

The same imperial logic applied: no disruption to energy supply, regardless of the human cost.

4.11 – IPOB and Kanu: Oil in the Age of Self-Determination

Nnamdi Kanu and IPOB have reframed Biafra’s oil not as a resource for Nigeria—but as a rightful inheritance stolen through war, colonial interference, and corporate collusion.

In IPOB rhetoric, the Niger Delta is not just geography—it is occupied territory, looted by a federal government backed by foreign oil interests. This messaging has deepened IPOB’s support base, especially among younger Niger Delta activists disillusioned with failed amnesty programs and empty development promises.

This ideological convergence—between environmental justice, ethnic self-determination, and anti-imperial critique—makes Biafra 2.0 far more dangerous to Britain than its 1967 version.

4.12 – Britain’s Investment in the Nigerian Status Quo

Today, Britain remains one of Nigeria’s top trading partners, with oil and gas still central to the relationship.

The UK government continues to train Nigerian military personnel, advise on counterterrorism, and support Abuja’s “national unity” efforts. But this support is also a strategy to protect commercial interests.

As Browne (2025) argues, British diplomacy in Nigeria has always followed a simple principle: “protect access to energy, and support the regimes that guarantee it.” Whether under military juntas or civilian governments, this rule has never changed.

4.13 – The Unlearned Lesson of Biafra

The Biafran War was not just a political crisis. It was an economic insurgency. And Britain’s response—military support disguised as neutrality—set the tone for decades of resource-driven conflict across Africa.

From Angola to Sudan, Western powers have repeated the same pattern: back central governments, ignore peripheral grievances, and prioritize stability over justice.

In doing so, they have often prolonged the very instability they claim to fear.

As Smith (2025) notes, Biafra was a moment when Britain could have supported dialogue, federal restructuring, or resource justice. Instead, it chose oil—and war.

4.14 – Oil, Empire, and the Future of the Nigerian State

More than 50 years after the end of the Biafran War, the question remains: Can Nigeria survive its oil wealth?

The British-imposed model—centralized extraction, elite brokerage, and external dependence—has created a brittle state. The calls for Biafra today are not echoes of tribalism, but rejections of a colonial economic design that still plagues Nigeria.

Britain, by failing to confront its past and continuing to back the status quo, remains complicit. Its empire may be gone, but its blueprint still governs the Delta—pipeline by pipeline, barrel by barrel.

Until that blueprint is torn up, the Biafran question will never go away. It will keep returning—in courtrooms, in radio broadcasts, in underground cells, and in oil-stained creeks—asking the same question Britain has never answered:

Who really owns the oil?

Part 5 – Abuja’s Playbook: Branding IPOB as Terrorists

The Nigerian state’s propaganda machine—and why Britain endorses it

5.1 – From Movement to Menace: The Label That Changed Everything

In September 2017, the Nigerian government officially designated the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) a terrorist organization. It did so through a Federal High Court ruling—issued in a matter of hours, with no public hearing, no cross-examination of evidence, and no meaningful judicial scrutiny.

The move was swift. Strategic. Political.

And, as critics argue, it marked the moment Nigeria rebranded a non-violent separatist movement into a national security threat—not because of violence, but because IPOB’s message was resonating.

To those in power in Abuja, IPOB wasn’t just a movement. It was a memory—of a war they feared could repeat, and a dream they could not afford to let spread.

5.2 – What Is IPOB? What Isn’t It?

Founded in 2012 by Nnamdi Kanu, IPOB emerged as a 21st-century successor to the Biafran dream: digitally connected, ideologically refined, and globally networked.

Its mission? A peaceful referendum for the independence of Biafra from Nigeria.

IPOB’s methods—civil disobedience, media broadcasting, international lobbying, diaspora mobilization—explicitly rejected armed struggle. And yet, as early as 2015, Nigeria’s security services began surveilling IPOB like a militant group.

The turning point came in 2017, following several mass protests in the South-East. The Nigerian Army launched “Operation Python Dance II”, deploying tanks and troops into Igbo cities. Days later, Kanu disappeared. IPOB was banned. The state had made up its mind: Biafra equals terrorism.

5.3 – The Terrorism Designation: How the Court Was Used

The court ruling that branded IPOB as a terrorist group was based on an ex parte motion—meaning IPOB was not present to defend itself. The government presented vague claims: incitement, hate speech, alleged attacks on police stations—none of which were adjudicated in a criminal trial.

There were no independent investigations. No forensic evidence. No named IPOB members tried or convicted for terrorism.

Still, the court ruled in favor of the government.

As Al Jazeera (2023) notes, this ruling became the linchpin of Abuja’s propaganda: a legal cover for mass arrests, extrajudicial killings, and surveillance.

From 2017 onward, IPOB’s name was not spoken as a political entity—it was uttered as a threat.

5.4 – Strategic Language: Terrorism as Narrative Control

Words matter. And “terrorist” is the most powerful label a government can use—domestically and internationally.

In branding IPOB as such, the Nigerian state didn’t just criminalize a group—it delegitimized a historical grievance. Suddenly, Biafra was no longer a civil question of self-determination. It was a threat to national security.

The media followed suit. So did foreign diplomats, though more cautiously.

As Okolocha (2023) notes, Nigerian media and state-aligned commentators began to link IPOB to insecurity, even when unrelated armed groups (like “unknown gunmen”) committed violence in the South-East. The branding was deliberate: blur the lines, shape the perception.

5.5 – The British Position: Strategic Ambiguity

Britain’s response to IPOB’s designation has been one of calculated ambiguity. The UK government has never officially proscribed IPOB. Yet, it has also never condemned Abuja’s designation—nor challenged the legality of Kanu’s detention under terrorism laws.

In its 2022 Country Policy and Information Note, the UK Home Office acknowledged reports of human rights abuses against IPOB members, but also repeated Nigerian government claims of IPOB’s “militant wing.”

The note reads:

“There are reports of IPOB-linked violence. However, evidence remains inconclusive.”

This is the playbook of plausible neutrality: acknowledge both sides, act on neither. In practice, this means silence when abuses occur—but cooperation when security interests align.

5.6 – The International Implications of the Label

Once a group is labeled “terrorist,” even if only domestically, it becomes a target everywhere.

Airlines monitor its members. Financial institutions restrict transactions. Foreign embassies deny visas. Global media adopts caution.

For IPOB, the designation has hindered its international advocacy, limited diaspora fundraising, and complicated its legal defense for Kanu.

As Gov.uk (2022) outlines, asylum claims from IPOB members are reviewed with skepticism, often citing “national security considerations” from Nigerian sources.

This creates a diplomatic paradox: Britain does not consider IPOB a terrorist group, but allows Nigeria’s designation to shape how it treats IPOB members.

5.7 – Who Are the Real “Unknown Gunmen”?

From 2021 onward, the South-East has seen a surge in violence: police stations burned, election offices attacked, security personnel killed.

The perpetrators? Officially: “unknown gunmen.”

Abuja, however, insists IPOB and its Eastern Security Network (ESN) are responsible—without presenting clear evidence. IPOB has denied involvement in multiple incidents, and no court has convicted any of its members for terrorism.

As Premium Times (2025) and News Guardian (2025) report, the Nigerian government routinely conflates “unknown gunmen” with IPOB in official briefings, press releases, and security reports.

This tactic serves a dual purpose:

- Justify militarization of the South-East.

- Ensure continued Western intelligence support under the counterterrorism umbrella.

5.8 – The Real Cost: Civilian Lives and Constitutional Rights

Behind the label lies a human toll. Since IPOB’s designation in 2017, dozens of its members have been arrested without warrants, detained without trial, and in some cases, disappeared altogether.

Several human rights organizations have documented extrajudicial killings during military operations in the South-East. Amnesty International has called for investigations. So far, none have occurred.

Meanwhile, curfews, lockdowns, and sweeping surveillance continue in Igbo-majority regions—despite the fact that no formal state of emergency has been declared.

In effect, the terrorism label has become a legal loophole for martial rule.

And Britain—still one of Nigeria’s top military and intelligence partners—remains eerily silent.

5.9 – The Psychology of Fear: Manufacturing Consent in the South-East

To maintain legitimacy for the IPOB terrorism label, Abuja has employed not only law and force—but fear.

In towns like Onitsha, Aba, and Owerri, residents live under a psychological siege: military checkpoints, sudden arrests, roadblocks, curfews. The state deploys what Okolocha (2023) refers to as “performative security theatre”—the visible presence of force to create an invisible boundary of fear.

This isn’t just about IPOB. It’s about sending a message to the population: dissent will be punished, and association will be criminalized.

The result? A region caught between state violence and insurgent suspicion, where many citizens are afraid to speak, organize, or protest—even peacefully.

5.10 – When Dissent Is Framed as Treason

In any democracy, peaceful agitation for self-determination is protected by law—especially when grounded in historical grievance. But in Nigeria, dissent is increasingly equated with disloyalty.

Kanu’s rhetoric, while provocative, does not promote jihad, bombings, or ethnic cleansing. IPOB has not hijacked planes, stormed embassies, or planted roadside IEDs. Yet it has been treated with more urgency than Boko Haram in its early years.

Why?

Because IPOB challenges the ideological foundation of the Nigerian state: that the union is sacred, indivisible, and final.

By branding IPOB as terrorists, Abuja sends a broader warning: questioning the structure is itself a crime.

5.11 – Britain’s Complicity: The Intelligence Pipeline

Britain’s endorsement of Nigeria’s anti-IPOB stance is not just passive. It is embedded in the intelligence-sharing architecture between both countries.

The UK trains Nigerian intelligence officers, supports counterterrorism operations, and provides equipment—ostensibly to fight groups like Boko Haram and ISWAP. But these tools are often redirected inward, toward IPOB.

According to Gov.uk (2022), Britain recognizes the “security partnership” as “robust and evolving.” Yet it fails to question whether counterterrorism resources are being misapplied for political repression.

When the UK refuses to challenge false terrorist designations, it becomes a silent enabler—helping Abuja militarize a constitutional crisis.

5.12 – The Legal Trap: A System Designed to Fail Activists

Once IPOB was labeled as terrorist, its members and sympathizers entered a legal black hole.

- Bail is routinely denied.

- Trials are endlessly delayed.

- Evidence is often “classified.”

- Charges are deliberately vague—ranging from sedition to terrorism to cybercrime.

Kanu himself has spent years in detention without a completed trial. Multiple courts, including Nigeria’s own Court of Appeal, have ruled in his favor. Yet the executive refuses to comply.

This is not law. It is theatre. The court becomes the stage, the government the director, and the defendant the prop.

And Britain, a country whose judiciary once served as Nigeria’s colonial model, says nothing.

5.13 – Global Hypocrisy: Terrorism as a Selective Label

The West has long warned about the abuse of terrorism laws—in China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. But in Nigeria, it has tolerated, even endorsed, similar abuses—because they align with Western economic and diplomatic interests.

When Uyghurs are labeled terrorists, Britain protests. When pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong are arrested under national security laws, Parliament debates. But when IPOB members are shot, jailed, or tortured, Britain shrugs.

As Al Jazeera (2023) highlighted during Kingsley Kanu’s legal challenge, the UK government refused to intervene—despite Nnamdi Kanu being a British citizen, and despite multiple human rights violations documented against him.

This is not neutrality. It is racialized selectivity.

5.14 – The Endgame: Repression as Policy, Silence as Strategy

The branding of IPOB as terrorists was never about justice. It was a preemptive strike—a political tool disguised as a legal decision, designed to fracture a growing movement.

And it worked—at least for now.

IPOB’s ability to operate publicly has been crippled. Kanu remains in detention. International support is limited. The diaspora is divided between fear and fatigue. Abuja has tightened its grip. Britain has protected its interests.

But at what cost?

When legal dissent becomes terrorism, when protest becomes criminality, and when silence becomes policy, a nation risks not only injustice—but instability.

IPOB’s branding is not just a Nigerian crisis. It is a mirror held up to the world, showing how the war on terror has become a war on resistance.

And Britain—once the architect of Nigeria’s unity—now sits as its quiet warden.

Part 6 – Extraordinary Rendition: Breaking Global Law

The 2021 Kenya operation—illegal, unethical, but quietly tolerated by Britain

6.1 – A Vanishing Act in Nairobi

In late June 2021, Nnamdi Kanu, British citizen and leader of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), walked into a building in Nairobi and never walked out.

What happened next is still shrouded in secrecy, denial, and diplomatic silence. But the essentials are clear.

According to The Guardian (2021) and legal filings submitted by Bindmans (2022, 2023), Kanu was abducted by unidentified men—widely believed to be working with Nigerian intelligence—held without charge, denied access to legal counsel, and secretly flown to Nigeria aboard a private aircraft.

No Kenyan court approved the extradition. No due process was followed. No one in the public knew where he was for more than a week.

What happened was not arrest. It was extraordinary rendition—and it broke international law.

6.2 – What Is Extraordinary Rendition? And Why Does It Matter?

Extraordinary rendition refers to the secret transfer of a person from one country to another without legal process, often involving torture, detention without trial, or denial of basic rights. It is illegal under:

- The UN Convention Against Torture

- The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights

- International Humanitarian Law

- And in this case, both Kenyan and Nigerian constitutions

The practice gained global notoriety after 9/11, when the U.S. used it to detain and interrogate terrorism suspects outside legal oversight. But in Kanu’s case, this method wasn’t used to fight terror—it was used to silence political dissent.

6.3 – Kenya’s Complicity: A Legal System Bypassed

The Kenyan government initially denied any role in Kanu’s arrest. But by 2025, after sustained pressure, the Kenyan High Court ruled that Kanu’s abduction and transfer were illegal and violated Kenya’s domestic and international obligations.

As reported by TheNicheNg (2025), the court declared that:

“The manner of the arrest, detention and transfer of Mr. Kanu contravened the law and constituted an unlawful rendition.”

This wasn’t just a diplomatic embarrassment—it was a judicial indictment of a rogue operation.

And yet, despite the ruling, no Kenyan official has been held accountable. No Nigerian official has been sanctioned. No international agency has investigated.

6.4 – Britain’s Silence: A Passport Forgotten

At the center of this case lies a hard question: Where was Britain?

Kanu is a British citizen. He holds a valid UK passport. His family resides in the UK. His arrest violated not only his rights—but the UK’s consular obligations under the Vienna Convention.

And yet, as Bindmans (2023) documents, the British government:

- Failed to protest his detention

- Did not demand consular access immediately

- Refused to classify the act as unlawful rendition

- Did not send legal observers to Nigeria

The UK High Court has since expressed “deep concern” over his treatment. But concern is not action. And concern has not freed him.

6.5 – Legal Evasion or Strategic Calculation?

The British government’s refusal to intervene is not apathy—it is strategy.

By avoiding official acknowledgment of the rendition, the UK government shields itself from legal obligation. It doesn’t have to apply pressure on Nigeria, sanction Kenyan actors, or defend Kanu in international courts.

As Premium Times (2025) reports, British officials have repeatedly insisted that the matter is “being monitored.” But monitoring isn’t advocacy. And diplomacy without defense is complicity.

This strategy serves two goals:

- Preserve UK-Nigeria relations, especially in trade and intelligence.

- Avoid setting a precedent that could apply to other dissidents.

6.6 – Abuja’s Endgame: Rendition as Message, Not Trial

Why did Nigeria choose rendition over legal extradition?

Because the goal was never prosecution—it was deterrence.

Kanu had become a symbol. His broadcasts reached millions. His diaspora network was expanding. His messaging was no longer fringe—it was becoming mainstream. To Abuja, he needed to be removed swiftly, dramatically, and without legal friction.

Rendition was the shortcut to silence.

And, as Okolocha (2023) observes, it also sent a message to the wider Biafran movement: “You can run, but you cannot hide—even in London, even in Nairobi.”

6.7 – The Nigerian Courts: Compromised Process, Endless Delay

Since being returned to Nigeria, Kanu has faced an endless legal limbo:

- His trial has been adjourned over a dozen times.

- Court rulings in his favor—such as the 2022 judgment declaring his detention illegal—have been ignored.

- Bail applications are denied with vague “security” reasoning.

- His lawyers report limited access, harassment, and surveillance.

As Bindmans (2022) notes, this violates Nigeria’s own laws, including constitutional guarantees of fair trial, freedom from arbitrary detention, and presumption of innocence.

In effect, the judiciary has become a holding mechanism—a way to keep Kanu in custody without the optics of extrajudicial killing.

6.8 – Rendition as Colonial Echo

What makes Kanu’s case uniquely disturbing is not just the illegality—it’s the historical echo.

During colonial rule, British authorities frequently used detention without trial, exile, and forced relocation to neutralize dissenters—from Kenyatta in Kenya to Azikiwe in Nigeria.

Now, postcolonial states like Nigeria have adopted the same tactics—often with quiet British approval.

As Okolocha (2023) compellingly argues, Kanu’s rendition is not just a contemporary human rights violation—it is a post-imperial ritual, inherited, perfected, and globalized.

6.9 – Human Rights, Selectively Applied

The irony of the Kanu case is that the same countries that preach human rights most loudly are the quietest when those rights are violated—if doing so protects their geopolitical interests.

The UK, EU, and even UN agencies have largely avoided applying pressure on Nigeria for Kanu’s illegal rendition or prolonged detention. When questioned, officials repeat cautious phrases like “we are monitoring the situation” or “we encourage respect for the rule of law.”

As Bindmans (2023) noted in its appeal filings, such positions are not neutrality—they are tacit endorsement of impunity.

If a British citizen had been abducted from Europe and flown to Iran or China, it would have triggered a diplomatic crisis. But Kanu? He’s rendered invisible.

6.10 – The Media’s Role in Sanitizing Illegality

The international media covered Kanu’s abduction in 2021—but only briefly, and mostly in passing.

As The Guardian (2021) and Premium Times (2025) reported, few headlines described the event as “extraordinary rendition.” Instead, softer language was used: “arrest,” “capture,” “transfer.” The legal violation—central to the story—was buried beneath political framing.

This language laundering matters. It shapes public perception and dulls the legal urgency.

The same global press that provides saturation coverage for Julian Assange or Alexei Navalny has largely failed to give Kanu’s case the sustained investigative attention it demands.

Why? Because challenging African governments—and by extension, their Western enablers—requires a level of editorial courage few are willing to summon.

6.11 – The Legal Options: Where Are the International Courts?

Despite the blatant illegality, no international tribunal has taken up Kanu’s case.

- The African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights has remained silent.

- The International Criminal Court (ICC) has not opened a file.

- The UN Human Rights Council has yet to appoint a special rapporteur.

Legal scholars argue that the case presents a clear opportunity to set precedent: political dissidents cannot be abducted, detained, and tried without due process.

Yet, global institutions hesitate—perhaps wary of confronting Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation and a major regional power, or perhaps unwilling to embarrass a Western ally complicit in silence.

6.12 – The Family’s Fight for Recognition

Since 2021, Kanu’s family—particularly his brother Kingsley Kanu—has waged a tireless legal campaign in the UK, Kenya, and Nigeria.

According to Al Jazeera (2023) and Bindmans (2022), Kingsley challenged the UK government in British courts for its refusal to recognize the illegality of the rendition and failure to protect a citizen abroad.

The case was dismissed.

Judges cited “foreign policy discretion” and “national interest”—legal phrases that shield governments from accountability. The message was clear: citizenship does not guarantee protection when political sensitivity is involved.

In doing so, the British state effectively reduced Kanu’s rights to paperwork—a passport in a drawer, not a shield in Nairobi.

6.13 – The Dangerous Precedent: A Playbook for Other Regimes

Kanu’s rendition sets a dangerous example, especially across the Global South.

- What’s to stop other governments from snatching dissidents abroad?

- What happens when citizenship no longer protects activists from state overreach?

- And what message does this send to other separatist or political movements?

If Kanu can be rendered from one African country to another without legal process—and without Western objection—then any critic, anywhere, is vulnerable.

What began as an isolated case becomes a playbook: of disappearance, denial, delay, and diplomatic cover.

6.14 – Empire’s Final Trick: Silence as a Weapon

More than four years after his illegal rendition, Nnamdi Kanu remains in detention—despite multiple court rulings, international legal arguments, and diplomatic appeals.

He is not a convicted terrorist. He has not been tried under credible evidence. His abduction has been ruled unlawful. And his rights, as both Nigerian and British citizen, continue to be violated.

Yet the most deafening part of his story is not the guns that seized him, nor the courts that stall his case.

It is the silence.

From London. From Nairobi. From New York. From The Hague.

That silence is not an accident. It is the final echo of empire—a quiet, deliberate, and powerful tool used to erase those who challenge the foundations it left behind.

And Kanu, despite being muzzled, still speaks louder than most.

Part 7 – Britain’s Silent Diplomacy Against Biafra

Behind closed doors: how the UK uses embassies and lobbying to choke IPOB abroad

7.1 – The Empire Never Left the Room

Publicly, Britain maintains the posture of a neutral observer in Nigeria’s domestic affairs. Officials recite familiar lines: “We support Nigeria’s unity,” “We urge respect for human rights,” and “We do not interfere in sovereign matters.”

But in diplomatic back channels—in visa decisions, intelligence briefings, and subtle bureaucratic pressure—the UK is deeply embedded in how the Biafra question is handled abroad.

This is not open suppression, but a strategy of soft containment: marginalize IPOB without public scandal, limit their reach without overt proscription, and prevent Biafra from ever becoming a serious diplomatic discussion.

Welcome to silent diplomacy, Britain’s most effective and least visible tool.

7.2 – The Art of Denial: Non-Designation, Real Consequences

Despite calls from the Nigerian government, the UK has not designated IPOB a terrorist organization. On paper, this signals a commitment to legal scrutiny and political neutrality.

But in practice, IPOB members—particularly those active in the diaspora—face systematic consequences:

- Visa denials and immigration delays

- Bank account freezes and funding scrutiny

- Surveillance of diaspora events and online activity

- Difficulty booking venues or registering NGOs

As Okolocha (2023) and Onyemechalu (2024) argue, this contradiction—non-designation paired with operational restrictions—is a diplomatic sleight of hand. It allows the UK to appear neutral while acting hostile.

7.3 – The London Broadcast: A Signal the UK Wants Muted

From a small studio in East London, Radio Biafra continues to beam pro-Biafra messaging across the globe. The station has become a cultural and political lifeline for millions of Biafrans in the diaspora.

Its broadcasts—often fiery, always unapologetic—have drawn the ire of Abuja. But they’ve also quietly unsettled the UK government, especially as IPOB’s messaging has evolved from grievance to organized international advocacy.

As Onyemechalu (2024) details in Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, the UK’s concern is not simply the message—it’s the growing infrastructure of transnational nationalism built around it: fundraisers, rallies, legal teams, policy briefings.

Radio Biafra is no longer fringe. It is diaspora diplomacy, and Britain knows it.

7.4 – The Pressure Behind the Scenes

While Britain has never admitted to cooperating in Kanu’s 2021 rendition, Bindmans (2023) and The Guardian (2025) reveal the UK government has received repeated lobbying from Nigerian officials to clamp down on IPOB activities within its borders.

This includes:

- Intelligence sharing on IPOB members

- Restrictions on IPOB-led events

- Quiet diplomatic memos discouraging sympathetic MPs from engaging with Biafran activists

Though none of this is written into law, it reflects a policy of pre-emptive discouragement: don’t ban IPOB—but don’t make life easy for them either.

7.5 – Embassies as Filters, Not Channels

In theory, diaspora groups should be able to raise political concerns through official diplomatic channels. In practice, Biafran advocacy groups report being shut out.

IPOB members and other pro-Biafra activists have tried, repeatedly, to engage with UK-based Nigerian diplomats—through petitions, letters, and civil society coalitions. The response? Silence.

At the same time, the British High Commission in Abuja works closely with the Nigerian government’s security establishment. According to Gov.uk (2022) policy documents, Britain supports “stabilisation and conflict prevention” strategies—which, in the Nigerian context, translates to intelligence and military backing for “unity.”

Thus, embassies become gatekeepers: amplifying state interests, muting resistance voices.

7.6 – The Unspoken Blacklisting of Diaspora Activists

Though not formally banned, Biafran activists in the UK are often treated as security risks.

Multiple reports from IPOB sympathizers cite:

- Unexplained visa denials for family members in Nigeria

- Police visits following pro-Biafra demonstrations

- Difficulties acquiring event permits

- UK charities being discouraged from partnering with IPOB-linked organizations

These measures are never attributed to official anti-Biafra policy. But as Onyemechalu (2024) describes it, they represent a “shadow regime of suppression”—where administrative power is wielded without judicial oversight.

The goal is not to arrest, but to wear down, isolate, and disempower.

7.7 – Parliamentarians and the “Nigeria File”

Inside Westminster, the Biafra issue is largely radioactive.

Several British MPs—especially those representing constituencies with significant Nigerian populations—have received IPOB petitions and letters. Few respond. Fewer still act.

One former MP, speaking anonymously to Premium Times (2025), described the “Nigeria file” as “the one you’re told to touch with gloves.” The British Foreign Office reportedly discourages public support for IPOB under the guise of avoiding “unhelpful escalation.”

It’s not a gag order. It’s something worse: discouraged interest.

When silence is incentivized, truth becomes unaffordable.

7.8 – Diplomacy Without Advocacy

What Britain practices with respect to Biafra is not classic diplomacy—it is gatekeeping under the banner of neutrality.

- It does not defend its own citizen, Nnamdi Kanu.

- It does not condemn Nigeria’s abuse of counterterrorism laws.

- It does not challenge the illegal rendition in Kenya.

- And it does not engage IPOB in good-faith dialogue.

Instead, it waits. Watches. And whispers behind closed doors.

This silence is strategic. It maintains economic ties with Nigeria, avoids parliamentary controversy, and prevents a larger public debate about Britain’s colonial role in Nigeria’s instability.

But the price of silence is mounting—and it may soon become too loud to ignore.

7.9 – Kanu’s Passport, Britain’s Dilemma

At the center of Britain’s diplomatic balancing act is a passport—Nnamdi Kanu’s UK citizenship, a status that should guarantee him basic consular protections. It doesn’t.

As Bindmans (2023) documented, despite multiple legal filings and media attention, the British government has refused to formally classify Kanu’s 2021 abduction as extraordinary rendition, let alone demand his release.

Instead, the Foreign Office maintains a deliberately ambiguous line:

“We are providing consular assistance and monitoring the situation.”

This bureaucratic phraseology serves a purpose—it avoids triggering legal accountability, while preserving relations with Abuja.

But it also exposes a double standard: not all British citizens are protected equally.

7.10 – Strategic Ambiguity as Foreign Policy Doctrine

In its dealings with IPOB and Biafra-related activism, the UK has weaponized a form of diplomacy that scholars now recognize as “strategic ambiguity.”

This involves:

- Refusing to take positions that might demand action

- Using vague language that allows for plausible deniability

- Privately coordinating with foreign governments while publicly appearing neutral

As Onyemechalu (2024) notes in Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, this is not inaction—it is governance through opacity. Britain’s goal is not to resolve the Biafra issue, but to contain it without owning it.

This ambiguity keeps oil flowing, trade uninterrupted, and Nigerian cooperation intact—at the expense of justice, transparency, and human rights.

7.11 – Biafra and Britain’s Post-Colonial Reputation

Every major democracy has its blind spots. For Britain, Nigeria is one of them.

In its post-colonial mythos, Britain paints itself as a benevolent former empire, committed to rule of law and democratic values. But Biafra is a rupture in that narrative.

To support Biafra’s right to self-determination—or even acknowledge the legitimacy of its grievances—would force the UK to reckon with its colonial engineering of Nigeria, its support for genocidal war policies in the 1960s, and its continued complicity in Nigeria’s current repression.

So instead, it opts for institutional forgetting.

Silence becomes a way to protect not just present interests—but historical amnesia.

7.12 – The Diaspora’s Pushback: A Resistance Without Borders

Despite the UK’s diplomatic stonewalling, the Biafran diaspora is not quieting down—it is adapting.