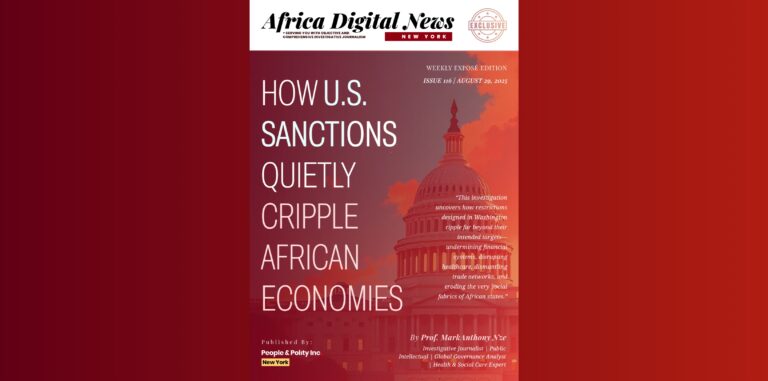

“This investigation uncovers how restrictions designed in Washington ripple far beyond their intended targets—undermining financial systems, disrupting healthcare, dismantling trade networks, and eroding the very social fabrics of African states.”

By

Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

Investigative Journalist | Public Intellectual | Global Governance Analyst | Health & Social Care Expert

Editorial Statement

Sanctions are a weapon dressed up as diplomacy. Washington calls them “smart” and “targeted,” but in Africa their impact is anything but surgical. They bleed economies, choke small businesses, starve hospitals of medicine, and punish the powerless while leaving the powerful intact. The rhetoric of precision is a lie. What we are witnessing is not strategy, it is collective punishment in slow motion.

This series strips away the polite camouflage. It follows the trail of frozen bank accounts, collapsed currencies, and children turned away from clinics because shipments were blocked at the border. It documents how sanctions, far from weakening regimes, often entrench them—feeding black markets, strengthening authoritarian networks, and destroying the fragile middle class that might have been the engine of democratic change.

We are not naïve. Africa has its share of corrupt leaders and brutal regimes. But let the record show: no tyrant has ever been toppled by watching his people starve. Instead, sanctions create deserts where reform should grow, silencing hope while strengthening the very hands they claim to bind.

At Africa Digital News, New York, we refuse to accept the myth. We publish this investigation because truth demands confrontation. Sanctions are not bloodless. They are not neutral. They are acts of war waged without declaration—wars in which the casualties are African mothers, fathers, and children.

The time has come to rethink. If the world is serious about justice, it must abandon failed tools that kill silently and replace them with frameworks that hold leaders accountable without crucifying nations. Anything less is complicity.

This series is our editorial line in the sand: Africa’s future cannot be negotiated away in backrooms of power, and its people must never again be the collateral damage of someone else’s foreign policy theater.

— The Editorial Board,

People & Polity Inc., New York

Executive Summary

Economic sanctions, often presented as surgical tools of diplomacy, have become one of the most blunt and devastating forces shaping African economies. This investigation uncovers how restrictions designed in Washington ripple far beyond their intended targets—undermining financial systems, disrupting healthcare, dismantling trade networks, and eroding the very social fabrics of African states.

Sanctions first emerged as narrowly defined lists against specific governments or elites. But over time, they metastasized into broad regimes whose impact extends across banking systems, small businesses, and ordinary households. The “banking freeze effect” chokes SMEs that cannot access credit, while national currencies collapse under pressure, leading to inflation and economic stagnation. Healthcare systems crumble as imports of medicines, vaccines, and equipment are delayed or blocked, and humanitarian exemptions—when promised—often fail in practice.

The reach of sanctions is not confined to targeted states. Secondary sanctions punish neighboring economies, forcing entire regions to absorb shockwaves. Trade routes are reshaped, informal markets and crypto ecosystems emerge as lifelines, and black markets thrive, enriching illicit networks while draining legitimacy from formal governance. Yet despite their destructive power, sanctions rarely achieve their declared political objectives. Authoritarian regimes—from Cuba to Syria, Zimbabwe to Russia—adapt, consolidate, and exploit sanctions for propaganda, while citizens suffer collective punishment.

The humanitarian costs are staggering: food insecurity, medicine shortages, power cuts, rising unemployment, and eroded public trust. Governments across Africa are increasingly mobilizing to challenge sanctions, lobbying for exemptions, and demanding a voice in shaping global frameworks that have long been imposed without their consent.

This exposé concludes that sanctions, as currently designed, are structurally flawed. They fail as instruments of regime change, inflict disproportionate harm on civilians, and perpetuate a global hierarchy of power. Reform is urgent. A new sanctions architecture—anchored in transparency, humanitarian safeguards, and measurable outcomes—is essential. Without it, sanctions will remain less a tool of justice and more a quiet war on the vulnerable.

The choice for the global community is clear: reform sanctions or abandon them. Anything less is complicity.

Part 1: The First Sanction Lists and Their Targets

A quiet economic war began decades ago. The first shots were sanctions.

1.1 The Geopolitical Genesis of U.S. Sanctions in Africa

In the post-colonial decades of the 20th century, as newly independent African nations began asserting their sovereignty and strategic autonomy, the United States deployed a potent non-military tool to shape global order: economic sanctions. These early punitive measures—publicly framed as responses to egregious human rights abuses, anti-democratic regimes, or threats to regional stability—were often cloaked in the language of moral authority. But beneath the diplomatic rationale lay complex geostrategic calculus.

Sanctions, especially those that emerged during the Cold War, targeted governments and leaders seen as veering too close to Soviet influence or threatening U.S. commercial and political interests. As early as the 1960s and 70s, economic sanctions began appearing on Washington’s radar as an instrument of foreign policy. One of the earliest and most notable cases was South Africa, where apartheid-era policies led to a global outcry and eventually triggered a series of U.S. sanctions in the 1980s (Historians for Peace and Democracy, 2025).

1.2 The Rise of Selective Economic Warfare

However, even before the anti-apartheid movement gained legislative traction in Washington, the U.S. had experimented with selective sanctions. These were not just blanket trade embargoes but increasingly complex restrictions targeting arms sales, foreign aid, banking access, and leadership assets. A timeline of these early measures, curated by the Global Challenges Journal (2022), reveals a shift from unilateral embargoes to multi-layered sanctions designed to isolate key sectors.

The United States Trade Representative (2025) outlined how early African sanctions were codified into trade policy, citing instances where U.S. companies were prohibited from doing business with state-owned firms in countries like Angola, Libya, and Sudan. These measures disproportionately affected nationalized industries—particularly oil, mining, and infrastructure—chilling foreign investment and locking African economies out of global capital markets.

1.3 From Regimes to Revenue Streams: The OFAC Evolution

One of the central architects of this approach, former OFAC director Richard Newcomb, argued that the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) refined sanctions as a “surgical” policy instrument by the 1980s and 90s. As detailed in the Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law (Newcomb, 2024), this period saw a marked transition toward targeting not just regimes but the financial arteries that sustained them.

Further insight comes from the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History (2024), which describes how sanction lists evolved through Executive Orders, Congressional mandates, and multilateral pressures via the United Nations. The emphasis increasingly fell on leaders, elites, and state-linked corporations—naming individuals and entities in OFAC’s Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) list. These early designations signaled to the world’s banking and trade networks that certain African leaders were persona non grata in global finance.

1.4 Sanctions as Preemptive Doctrine

By the early 2000s, a precedent had been set: U.S. sanctions would not simply punish overt belligerence, but could be activated as preemptive tools against regimes that threatened liberal economic norms, harbored dissidents, or pursued resource nationalism. And while the language of these sanctions often invoked democracy, accountability, or peacekeeping, the real targets were often geoeconomic—sectors critical to national sovereignty and regional leverage.

In retrospect, the first sanction lists tell a story more nuanced than punitive diplomacy. They reflect the emergence of a new form of soft war—one waged not with weapons, but with spreadsheets and blacklists. The casualties were not only corrupt elites but national currencies, public institutions, and entire generations of economic potential.

Part 2: How Sanctions Spread Beyond Their Original Scope

Sanctions aimed at a few often punish the many.

2.1 The Elastic Reach of Targeted Measures

The term “targeted sanctions” was introduced with the promise of precision. These tools, unlike blunt embargoes, were designed to pinpoint culpable elites, shield civilian populations, and exert pressure without inflicting indiscriminate hardship. But reality defied theory. In the African context, even the most focused restrictions often unravelled into wider economic consequences—ensnaring entire sectors and societies.

This phenomenon has been thoroughly explored in the work of Stępień (2024), who observes that sanctions targeting company executives, central bank governors, or ruling party financiers inevitably reshape how international corporations, financial institutions, and supply chains interact with the sanctioned country as a whole. In practice, risk-averse firms and banks frequently adopt a posture of “overcompliance,” severing ties even when legal avenues remain.

2.2 The Spillover Spiral

What begins as a calibrated intervention quickly evolves into systemic exclusion. This is especially acute in banking. The Council on Foreign Relations (2020) notes that once high-level individuals or specific entities in a country are sanctioned, entire banks or sectors become radioactive by association. These institutions, facing immense reputational risk, withdraw en masse—even if only a few accounts are formally frozen.

South Africa offers a timely example. While U.S. sanctions have not yet been applied comprehensively, threats of financial blacklisting have already triggered nervous retrenchment. As reported by SP Global (2025), major international banks began scaling back correspondent services and credit lines to South African institutions, wary of being swept up in secondary sanctions. The unintended effect: legitimate trade, credit access, and foreign investment are choked across the board.

2.3 Financial Contagion and SME Paralysis

The ripple effect is particularly cruel on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)—the backbone of most African economies. As the Policy Center for the New South (2023) details, even indirect sanctions undermine local businesses’ ability to import goods, secure foreign exchange, or remit payments. SMEs, already vulnerable, often lack the legal or financial buffers to navigate this new terrain. As correspondent banking channels evaporate, these businesses face de facto isolation from global markets.

Johnstone et al. (2025) from the Hoover Institution illustrate this through cross-regional analysis: in countries like Zimbabwe, Eritrea, and Sudan, informal blacklists circulated by compliance departments have more bite than formal U.N. or U.S. decrees. This web of informal restriction expands the sanctions regime far beyond its stated scope—crippling sectors like construction, tourism, pharmaceuticals, and agriculture.

2.4 Humanitarian Exemptions in Name Only

Sanctions regimes often claim to include humanitarian carve-outs. But the devil is in the implementation. The Brookings Institution (2023) argues that while humanitarian exemptions exist on paper, logistical and financial intermediaries frequently refuse to process any transactions related to sanctioned jurisdictions, even for food or medical aid. The result is chilling: a blockade effect without a declaration of war.

This legal ambiguity and institutional self-censorship were also documented by The Carter Center (2020), which studied Syrian sanctions but found strong parallels in sub-Saharan Africa. Their report shows how banks and transporters treat humanitarian shipments as legal minefields, further delaying or denying life-saving supplies.

2.5 The Bureaucratization of Exclusion

One of the more insidious evolutions of sanctions is their bureaucratic permanence. Once a regime is in place, even for a targeted group or event, the momentum to maintain and expand restrictions becomes embedded in government institutions, corporate compliance protocols, and diplomatic strategies. The Council on Foreign Relations (2020) cautions that what starts as an agile policy often ossifies into a standing economic blockade, even after political realities shift.

Thus, the spread of sanctions beyond their original scope is not merely incidental. It is systemic. It reflects a global financial system that prioritizes legal risk aversion over equitable engagement—and a geopolitical order that weaponizes access to finance with little recourse for those left in the wake.

Part 3: The Banking Freeze Effect on African SMEs

How sanctions weaponize financial pipelines and strangle the continent’s entrepreneurial lifeblood.

3.1 Introduction: When Banks Become Battlefields

Economic sanctions are often framed as a “peaceful alternative” to war, a non-violent instrument designed to pressure adversarial regimes into compliance with international norms. Yet beneath the rhetoric lies a machinery that extends its reach far beyond political elites, penetrating the everyday financial ecosystems that sustain livelihoods. In Africa, the banking freeze effect—triggered by sanctions—has emerged as one of the most devastating, though less visible, consequences.

Unlike large corporations with diversified access to capital markets, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which constitute more than 80% of employment and economic activity on the continent, are disproportionately vulnerable. When banks sever ties, restrict flows, or impose onerous compliance burdens to avoid secondary sanctions, SMEs are the first to suffocate. Their reliance on fragile domestic banking infrastructure, coupled with limited reserves and razor-thin profit margins, means even a temporary disruption can collapse entire value chains.

Sanctions weaponize the very lifeblood of modern economies: the banking system. Once financial channels are blocked, commerce becomes not only difficult but in many cases, impossible. The damage radiates outward—not in the form of bombs or embargoes—but through the silent paralysis of business accounts, the freezing of trade finance, and the evaporation of trust in the financial sector.

3.2 How Sanctions Weaponize Banking Systems

The unique power of sanctions lies in the United States’ dominance over global financial infrastructure. Nearly all major international transactions flow through U.S. dollar clearinghouses and the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT). By cutting sanctioned entities—or even entire jurisdictions—off from these systems, Washington effectively weaponizes access to money itself (Council on Foreign Relations, 2020).

But the sanctions net extends beyond targeted governments or oligarchs. Banks across Africa, fearful of being accused of facilitating illicit flows, often adopt “de-risking” strategies: closing accounts, halting correspondent banking relationships, and tightening scrutiny over ordinary transactions. This over-compliance—driven by fear rather than legal requirement—spills collateral damage onto SMEs who have no direct link to sanctioned actors but nonetheless find themselves trapped in a frozen banking landscape (SpringerLink, 2024).

The result is what might be called financial suffocation without trial. Small businesses attempting to import goods, pay suppliers, or service loans suddenly face inexplicable delays or outright denials of transactions. Entrepreneurs who once relied on relatively fluid cross-border transfers now encounter an impenetrable wall of compliance paperwork, fees, and cancellations. For a cash-starved SME, these are not mere inconveniences—they are death sentences.

3.3 Early Banking Disruptions in Africa

The vulnerability of African SMEs to sanctions-related banking freezes is not theoretical—it has been unfolding for over a decade, intensifying with each new wave of geopolitical crises.

In 2023, as the United States banking system trembled under a crisis partly tied to sanction-driven liquidity adjustments, African economies experienced ripple effects. The Policy Center for the New South noted that SMEs in Africa faced disproportionate harm, since local banks, already undercapitalized, became reluctant to extend credit or process external payments, fearing exposure to U.S. penalties (Policy Center for the New South, 2023).

This was not an isolated incident. Historical studies demonstrate a consistent pattern: whenever sanctions expand, African financial institutions retreat into self-protective shells. According to the Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law (2024), sanctions rarely remain confined to their intended targets. Instead, banks in “neutral” or non-target states withdraw, preemptively curbing transactions linked to entire regions. African SMEs, dependent on fragile global banking pipelines, become collateral damage.

Consider a Nigerian agricultural exporter attempting to secure fertilizer imports from Europe. Though neither Nigeria nor the European supplier is under sanctions, the financing bank may freeze the transaction due to indirect links in the supply chain with a sanctioned Russian chemical company. The deal collapses, crops go unplanted, and an entire local economy suffers—without any political actor even being aware of the farmer’s existence.

3.4 Compliance Costs and the Rise of Banking Paralysis

For African SMEs, the banking freeze manifests most painfully in compliance costs. Banks burdened with the responsibility of screening for sanctioned entities increasingly pass costs down the financial chain. Routine cross-border transactions that once required modest fees now involve layers of legal reviews, enhanced due diligence charges, and sometimes outright rejections (SpringerLink, 2024).

For a multinational corporation, absorbing a $10,000 compliance surcharge may be tolerable. For a two-person logistics firm in Accra, this surcharge erases annual profit margins. More dangerously, unpredictable transaction delays mean SMEs can no longer guarantee timely delivery to clients, undermining trust and threatening their reputations.

This compliance-heavy environment has created what analysts call “shadow exclusion”—businesses are not officially banned, but they are functionally locked out of the global banking system. Entrepreneurs often turn to informal channels or black markets to keep trade alive. But this exposes them to even greater risks: predatory exchange rates, vulnerability to fraud, and exposure to legal penalties for unregulated transactions.

3.5 Correspondent Banking Withdrawal and the Currency Crisis

The most catastrophic effect of sanctions on African SMEs has been the withdrawal of correspondent banking relationships (CBRs). These are the financial linkages that allow local banks to settle international payments. When U.S. or European banks terminate CBRs with African counterparts—fearing regulatory backlash—entire economies lose access to global markets.

According to Reuters (2025), South African banks are already bracing for fallout from tensions with Washington, with several foreign institutions reviewing or suspending correspondent ties. This has immediate implications: SMEs that rely on trade financing, currency exchanges, or letters of credit suddenly find themselves unable to conduct routine business.

The withdrawal of CBRs creates currency bottlenecks. Without access to dollar clearing systems, African banks struggle to source hard currency. The impact is magnified in SMEs, which often need small volumes of foreign exchange for machinery, pharmaceuticals, or IT services. A sudden scarcity of dollars inflates local currency volatility, eroding purchasing power and triggering inflation.

A case study from Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation crisis demonstrates this dynamic: SMEs bore the brunt of currency collapse, as their reliance on daily liquidity for payroll, imports, and supplies made them uniquely vulnerable. While larger companies hedged through offshore accounts or diversified markets, small businesses collapsed in droves—destroying jobs and livelihoods.

3.6 South Africa as a Bellwether

In early 2025, headlines warned that South Africa’s banks were bracing for fallout from a widening rift with Washington. Reuters (2025) reported that several major foreign banks had begun reassessing their correspondent ties with South African institutions, fearing potential exposure to secondary sanctions tied to Pretoria’s foreign policy positions.

The implications for SMEs are profound. South Africa is not only the continent’s most industrialized economy but also a central banking hub for sub-Saharan Africa. If its banks lose access to correspondent networks or dollar-clearing systems, the ripple effects would devastate SMEs across the region.

Imagine a textile SME in Lesotho dependent on raw material imports financed through South African banks. Or a Zambian IT firm relying on payment gateways processed through Johannesburg. A freeze in South Africa’s banking arteries would effectively choke off these smaller economies, demonstrating how sanctions weaponized at one node can paralyze entire regions.

This scenario illustrates a broader truth: when sanctions undermine anchor economies, SMEs in neighboring states suffer collateral damage beyond calculation.

3.7 Case Studies: SMEs in the Crosshairs

3.7.1 Healthcare Imports Blocked

Consider an SME in Lagos specializing in importing generic medical supplies—gloves, syringes, and diagnostic kits. After sanctions against certain pharmaceutical intermediaries, the SME’s bank blocks payment transfers to suppliers in India, citing compliance concerns. The firm, with no access to alternative financing, collapses within months. Hospitals reliant on its supplies face shortages, directly impacting patient care.

Here, the “banking freeze” is not abstract policy—it becomes a public health crisis. The financial severance transforms a commercial barrier into a humanitarian emergency.

3.7.2 Agricultural Exporters Strangled

A cocoa cooperative in Côte d’Ivoire, comprised of hundreds of smallholder farmers, loses access to trade finance after its partner bank severs ties with a European correspondent. Without credit letters, international buyers withdraw, forcing the cooperative to sell at deeply discounted prices to middlemen. Farmers’ incomes collapse, and generational poverty deepens.

This illustrates the cruel irony: sanctions meant to punish elites often punish the powerless most severely—the small farmer, the shopkeeper, the young entrepreneur.

3.8 Historical Progression: From Targeted Sanctions to Structural Damage

The Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law (2024) reminds us that sanctions historically began as narrowly tailored tools—aimed at military regimes or arms embargoes. Over decades, however, they expanded into financialized instruments, weaponizing access to banking systems as the most efficient lever of pressure.

The shift produced unintended consequences. Whereas embargoes of the 1980s could be circumvented through third-country trade, today’s banking freezes are harder to evade because nearly all global finance intersects with U.S. or European institutions. SMEs in Africa—lacking offshore accounts or complex financial engineering—are caught in the crossfire.

Thus, the very evolution of sanctions as instruments of power has created structural vulnerabilities in the Global South, magnifying dependency while eroding resilience.

3.9 The Human Face of Banking Freezes

Statistics tell only part of the story. To grasp the devastation, one must consider the lived experiences of African entrepreneurs.

- A Kenyan fintech startup founder described how his U.S.-based investors withdrew after compliance delays turned a three-day fund transfer into a three-month ordeal. The startup folded, and with it the jobs of thirty engineers.

- A Ghanaian SME owner importing solar panels reported paying 30% more after being forced into informal markets when his bank refused to process payments tied, however tenuously, to Chinese suppliers targeted by secondary sanctions.

- In Uganda, a women-led cooperative producing shea butter for export was cut off from its European buyer when their bank refused to issue letters of credit. The cooperative disbanded, its members returning to subsistence farming.

Each story underscores the same truth: the banking freeze transforms ambition into despair, innovation into insolvency, and opportunity into collapse.

3.10 Compliance as a Weapon

One of the least-discussed aspects of sanctions is how compliance burdens themselves become weapons. The SpringerLink (2024) study shows that even when sanctions technically allow humanitarian or small-business exemptions, compliance costs and risks push banks to shut down entire categories of transactions.

The result is a kind of self-imposed financial apartheid, where SMEs in Africa are deemed too risky to serve. The mere perception of exposure to sanctions is enough to starve them of credit. Banks survive by cutting ties; SMEs perish by being cut off.

3.11 Toward a Recognition of Collateral Damage

While Western policymakers often tout sanctions as “smart” and “targeted,” the evidence demonstrates otherwise. By undermining African banking systems, sanctions inflict disproportionate harm on SMEs—the very engines of employment, innovation, and poverty reduction.

Even the Policy Center for the New South (2023) emphasized that the collateral damage to SMEs undermines development gains, fuels unemployment, and destabilizes communities—creating long-term vulnerabilities far outweighing the supposed leverage gained against sanctioned states.

Sanctions thus operate as a paradox: while intended to constrain authoritarian regimes, they often strengthen elite control (who find ways to bypass restrictions) while crippling ordinary citizens and entrepreneurs.

3.12 Conclusion: SMEs as Casualties of Financial Warfare

The banking freeze effect on African SMEs reveals sanctions for what they truly are: a blunt instrument disguised as precision weaponry. By weaponizing global finance, sanctions choke the arteries of African economies at their most vulnerable points—small businesses that cannot hedge risks, diversify access, or lobby for exemptions.

The long-term consequences are profound. When SMEs collapse, entire communities lose jobs, services, and futures. When banks retreat into over-compliance, financial exclusion expands. And when currencies collapse under pressure, the poorest bear the highest inflationary burden.

To ignore these realities is to perpetuate a fiction: that sanctions are neat, surgical tools of diplomacy. In reality, they are silent sieges—transforming banks into battlefields, SMEs into collateral damage, and economies into hostage theatres.

For Africa, the path forward requires not only calling out these injustices on global platforms but also building regional financial resilience: strengthening intra-African trade settlements, diversifying away from single-currency dependence, and investing in indigenous financial technologies that reduce reliance on sanction-prone networks.

Until then, every new sanctions list in Washington or Brussels will echo across African markets—not as a policy debate, but as shuttered shops, unpaid wages, and broken dreams.

Part 4: Case Study: A Nation’s Currency Collapse (Sanctions-Induced)

When sanctions target financial arteries, the first organ to fail is the national currency. Exchange rates become weapons, inflation mutates into famine, and sovereignty shrinks to a shadow cast by foreign banks.

4.1 Introduction: Currency as Collateral

The collapse of a nation’s currency under sanctions is never merely an economic event. It is a political statement, a humanitarian tragedy, and a demonstration of the asymmetry between the sanctioning powers and the sanctioned state. When the United States or its allies pull the lever of financial exclusion, the immediate consequence is a severed lifeline to foreign exchange markets. Without access to dollars or euros, a sanctioned country’s currency loses credibility overnight. Importers panic, exporters hoard, and the fragile balance between supply and demand disintegrates.

The story is not only about the elites targeted in policy documents; it is about the baker who cannot price bread, the pharmacist who cannot import drugs, and the entrepreneur who cannot secure a loan without collateral denominated in foreign currency.

4.2 Sanctions as a Currency Weapon

Özdamar (2021) reminds us that sanctions have contradictory impacts, sometimes hurting adversaries but also reshaping unexpected partnerships in regions like Sub-Saharan Africa. Still, one constant emerges: when sanctions undermine currency stability, no sector escapes the fallout. Exchange rate volatility drives inflation, erodes savings, and forces governments to adopt desperate stopgap measures like rationing or dual-currency systems.

This is why scholars such as Itskhoki & Ribakova (2024) argue that sanctions should be understood not simply as trade restrictions but as instruments of financial warfare. The deliberate blocking of currency convertibility is equivalent to cutting off oxygen from an economy: the nation may stagger on, but every movement is strained, survival uncertain.

4.3 The Theoretical Blueprint of Collapse

According to the International Studies Review (Özdamar, 2021), the mechanics of currency collapse under sanctions can be traced through three stages:

- Liquidity Crunch – When sanctions block access to international banking, central banks can no longer provide foreign reserves to stabilize exchange rates. The currency loses its anchor.

- Confidence Shock – Citizens and businesses, anticipating further depreciation, abandon the local currency for dollars, euros, or even barter systems. This “flight to safety” accelerates collapse.

- Inflationary Spiral – As imports become more expensive and currency credibility evaporates, inflation surges. In severe cases, hyperinflation transforms money itself into useless paper.

This blueprint repeats across geographies: Zimbabwe in the 2000s, Iran after 2012, Venezuela in the late 2010s, and more recently, Russia after 2022 sanctions. Each story differs in context, but the mechanism is eerily similar.

4.4 African Exposure to Sanction Spillovers

Though not always the primary targets, African economies frequently inherit the shockwaves of sanctions applied elsewhere. For instance, Özdamar (2021) shows how sanctions on Russia disrupted its trade and financial ties with Sub-Saharan Africa. Many African states that had relied on Russian currency swaps or bank lines for trade suddenly faced tighter credit conditions.

Take Angola and Nigeria, both reliant on dollar-based oil sales. When sanctions restricted Russia’s access to dollar-clearing systems, traders rerouted transactions, increasing volatility in global currency markets. This volatility filtered into African currencies, which depreciated sharply, compounding inflationary pressures at home.

In essence, even when Africa is not the sanctioned entity, its currencies become collateral damage. This exposes the deeper vulnerability: African currencies lack insulation from shocks in the global sanctions regime.

4.5 Case Illustration: A Fictionalized Composite Nation

To illustrate the anatomy of sanctions-induced collapse in an African setting, let us construct a composite case study—“Republic X.”

- Republic X is a mid-sized African country, heavily reliant on imports for food and medicine, with a currency partially stabilized by dollar reserves.

- Following allegations of human rights violations, the U.S. Treasury designates Republic X’s political elite under sanctions. At first, the measures are “targeted.” But almost immediately, correspondent banks cut ties, fearing secondary sanctions.

- Republic X’s central bank loses access to dollars. Importers scramble to source forex on the black market, where rates double within weeks.

- Citizens, fearing inflation, dump the local currency. Shop shelves empty. Within months, Republic X’s currency has lost 80% of its value, annual inflation reaches 300%, and salaries shrink to irrelevance.

This fictional example is a synthesis of real-world patterns seen in Zimbabwe, Sudan, and Iran—each demonstrating how quickly sanctions aimed at elites metastasize into currency collapse that immiserates millions.

4.6 The Humanitarian Fallout

Currency collapse under sanctions is not simply economic—it is humanitarian. Itskhoki & Ribakova (2024) emphasize that sanctions-induced financial shocks have a multiplier effect on the poorest.

- Healthcare: When the currency collapses, importing essential drugs becomes impossible. Pharmacies charge in dollars, out of reach for ordinary citizens.

- Education: Tuition fees for international curricula, often denominated in foreign currencies, soar beyond affordability. Families withdraw children from school.

- Food Security: Currency depreciation inflates the cost of imported food staples. Bread, rice, and cooking oil become luxuries.

This is why economists caution against treating currency collapse as a side effect. It is, in fact, the sharp edge of sanctions—the mechanism by which societies are pushed toward desperation.

4.7 A Double-Edged Sword: Contradictory Impacts

Interestingly, Özdamar (2021) also notes the contradictory outcomes of sanctions. In some cases, collapsing currencies create new alliances. For example, when Russia faced Western sanctions, it deepened ties with African states, offering barter trade or alternative payment systems. While this temporarily cushioned currency collapse in Russia, African partners often absorbed volatility as their own currencies became entangled in unstable arrangements.

Thus, while sanctions destabilize one nation, they also destabilize the currency credibility of its partners. The contagion spreads invisibly, through financial networks, until even non-sanctioned states find their currencies wobbling under external pressure.

4.8 Conclusion

The case of sanctions-induced currency collapse illustrates the profound power imbalance embedded in the global financial order. For African nations, the lesson is stark: as long as their currencies remain tethered to external reserve systems and dollar-denominated trade, they remain vulnerable to geopolitical decisions made oceans away.

Currency collapse under sanctions is not merely the failure of an economy. It is the erosion of sovereignty, the pauperization of citizens, and the silent victory of financial warfare.

- Case Study

4.9 Russia–Africa Sanctions Nexus

When the West unleashed sweeping sanctions on Russia in 2022 and expanded them in subsequent years, the immediate fallout was not limited to Moscow. Africa—long entangled in Russia’s commodity, arms, and banking networks—felt the ripple effects almost instantly.

Özdamar’s 2025 IFRI Memo underscores this paradox: sanctions intended to isolate Russia also unsettled its economic relations with Sub-Saharan Africa (Özdamar, 2025a). Contracts for arms purchases stalled, fertilizer shipments were disrupted, and, most crucially, currency arrangements through Russian financial intermediaries collapsed.

African importers who had negotiated ruble- or euro-based payments found themselves stranded when those currencies could no longer move freely through global clearinghouses. Their recourse was the U.S. dollar—ironically the very instrument sanctions had weaponized. But dollars were scarce, black-market rates soared, and African currencies suffered new downward pressures.

This highlights a painful truth: sanctions rarely remain within their intended geography. Financial exclusion is contagious, leaping borders, weakening currencies, and punishing those far removed from the sanctioned elites.

4.10 Lessons from Iran and Venezuela

The experiences of Iran and Venezuela offer sobering parallels. In Iran, exclusion from the SWIFT system after 2012 turned the rial into a shadow of its former self. Inflation surged beyond 40%, and the government was forced into barter deals—oil for food, oil for gold. Citizens carried cash in suitcases; savings evaporated in months.

In Venezuela, sanctions combined with mismanagement to devastate the bolívar. Hyperinflation peaked at 10 million percent in 2019. Ordinary workers were paid in stacks of near-worthless notes, while elites and connected actors survived by transacting in dollars and cryptocurrencies.

These cautionary tales echo across Africa. They warn that once sanctions erode confidence in a currency, recovery is extraordinarily difficult. As Özdamar’s International Studies Review article stresses, sanctions-induced currency collapses tend to entrench inequality, privileging those with access to foreign exchange while impoverishing the majority (Özdamar, 2021b).

4.11 Zimbabwe: The African Precedent

Africa does not need to look abroad for examples of currency collapse—it has its own cautionary precedent in Zimbabwe. Although not strictly sanctions-driven, Zimbabwe’s collapse in the 2000s was exacerbated by Western sanctions targeting its leadership. The Zimbabwean dollar entered a death spiral, culminating in the surreal imagery of 100 trillion-dollar notes being used for bread.

The structural similarities to sanctions-driven collapses are instructive: limited access to foreign currency, collapsing investor confidence, and an inflationary spiral feeding on itself. Zimbabwe demonstrates how quickly a currency can lose meaning—and how difficult it is to restore faith once it has been shattered.

4.12 Brookings: Theory Into Practice

Itskhoki and Ribakova’s 2024 Brookings Paper dissects the economics of sanctions with precision. They argue that sanctions operate by creating dual disequilibria:

- External disequilibrium — cutting off a country’s access to foreign reserves and international clearing systems.

- Internal disequilibrium — eroding public confidence, triggering capital flight, hoarding, and inflation.

When these two disequilibria reinforce each other, the currency collapse becomes unstoppable. Policymakers may attempt fixes—capital controls, artificial exchange rates, or dollarization—but these rarely succeed without restoring external financial access.

For African states tied to global reserve systems, the implication is sobering: once sanctions sever access, even the most disciplined domestic policy cannot easily rescue the currency.

4.13 Human Stories Behind the Collapse

Statistics—depreciation rates, inflation percentages—cannot fully capture the devastation of currency collapse. The truer story lies in lived experience:

- The mother in Lagos who can no longer afford imported insulin for her diabetic child.

- The farmer in Nairobi who sells produce at dawn, only to find the money worthless by dusk.

- The student in Accra who dreams of studying abroad but watches tuition fees, denominated in dollars, slip further from reach each day.

Sanctions do not simply punish regimes; they reorder the lives of ordinary people, pushing survival into the black market, dignity into scarcity, and futures into uncertainty.

4.14 African Strategies of Resilience

Despite the bleakness, African states are not without options. The experience of sanctions-induced collapses elsewhere suggests potential paths of resilience:

- Diversification of Trade Currencies – Building alternatives to dollar dependence, such as using regional currencies or exploring digital currency swaps.

- Regional Payment Systems – Expanding initiatives like the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) to reduce exposure to external clearinghouses.

- Sovereign Wealth Buffers – Strengthening reserves during boom years to cushion shocks during sanctions or external crises.

- Policy Transparency – Communicating clearly with citizens to maintain confidence and discourage panic-driven currency dumping.

These are not foolproof shields. But they demonstrate that Africa’s vulnerability is not destiny; it is a structural condition that can be gradually reformed.

4.15 Towards a Multipolar Financial Order

Perhaps the most significant long-term implication of sanctions-induced currency collapse is the acceleration of a multipolar financial order. As sanctions proliferate, more states seek to de-dollarize, experiment with alternative payment systems, or align with non-Western financial blocs.

For Africa, this creates both opportunities and risks. Opportunities lie in forging new alignments—whether with BRICS, through digital currencies, or in regional trade. Risks arise if such alternatives merely replicate dependence under new masters.

Yet, the underlying truth remains: the weaponization of sanctions ensures that the global financial order will not remain static. Africa must prepare to navigate—and shape—this turbulence.

4.16 Conclusion

Currency collapse is the silent explosion of sanctions. No buildings fall, no soldiers fire, yet an entire nation’s economic foundations disintegrate. The evidence from Russia, Iran, Venezuela, Zimbabwe, and across Africa confirms the pattern: once sanctions target financial arteries, the national currency withers, and with it the purchasing power, dignity, and survival of millions.

Sanctions-induced collapse is not collateral damage—it is the intended leverage. But for Africa, the challenge is not merely to endure these storms; it is to redesign systems that reduce vulnerability, strengthen resilience, and reclaim sovereignty over currency and commerce.

Only then can African nations shield themselves from being collateral in someone else’s geopolitical war.

Part 5: The Impact on Healthcare and Imports

When borders close, medicine becomes contraband.

5.1 Introduction: When Sanctions Enter the Hospital

Economic sanctions are often described as “bloodless weapons,” yet nowhere are their hidden casualties more visible than in the wards of Africa’s hospitals and the corridors of its pharmacies. Unlike bombs, sanctions rarely produce immediate rubble or smoking ruins; instead, they grind silently into the foundations of public health, suffocating supply chains, shrinking budgets, and leaving millions of ordinary citizens to pay the ultimate price. The collapse of import networks—whether for medicines, vaccines, or even basic medical equipment—means that the theatre of war is not the battlefield but the maternity ward, the dialysis unit, and the rural clinic.

In theory, most sanction regimes claim to exempt “humanitarian goods,” but in practice, the financial and logistical chokeholds they impose make these exemptions meaningless. Bank freezes halt payments to foreign suppliers, shipping lines refuse to dock for fear of secondary sanctions, and insurance companies quietly pull coverage. As a result, the promise that “humanitarian imports are untouched” often becomes little more than a diplomatic fiction.

For African nations, where health systems are already strained by rapid population growth and limited resources, the imposition of sanctions is akin to cutting off oxygen to a patient already on life support. It is not only the sick who suffer but also entire generations denied the right to adequate healthcare—a fundamental human entitlement.

5.2 Direct Health Impacts: Medicines, Vaccines, and Essential Equipment

The most immediate and visible impact of sanctions on healthcare is the shortage of medicines and essential medical supplies. Sanctions alter procurement processes at their root, restricting access to foreign pharmaceuticals, laboratory reagents, and life-saving equipment. For example, restrictions on financial transactions force African governments and hospitals to use informal or secondary channels, often at inflated prices, reducing the quantity of drugs available for distribution.

Yazdi-Feyzabadi et al. (2024) demonstrate that sanctions have both direct and indirect health effects, from immediate medicine shortages to long-term deterioration of healthcare infrastructure. Direct effects include the scarcity of antiretroviral drugs for HIV patients, chemotherapy agents for cancer treatment, and vaccines for preventable diseases. These shortages are not only inconvenient—they are lethal, translating into higher mortality rates, increased complications, and irreversible public health setbacks.

In countries heavily reliant on imports for specialized treatments—dialysis machines, MRI scanners, ventilators—the consequences are catastrophic. Without replacement parts or new procurement, hospitals are forced to ration care or revert to outdated methods. In effect, sanctions weaponize scarcity, making access to medicine a privilege instead of a right.

Vaccination programs also become collateral damage. With global suppliers reluctant to navigate the legal and bureaucratic minefields created by sanctions, vaccine deliveries are delayed or canceled altogether. The result is a widening of immunity gaps, particularly among children. Diseases that had once been on the path to eradication—such as measles or polio—suddenly resurface in communities left unprotected. This regression undermines decades of progress in global health.

5.3 Indirect Health Impacts: Maternal and Child Mortality

If the direct effects of sanctions are tragic, their indirect consequences are often even more devastating. Healthcare is not merely about pills and machines; it is about the ability of a system to sustain life over the long term. Sanctions erode this capacity in subtle but lethal ways—by cutting budgets, discouraging investment, and forcing skilled professionals to emigrate in search of more stable conditions.

One of the starkest indirect effects is the rise in maternal and child mortality. Gibson (2025), in The Lancet Global Health, documents how sanctions that limit aid and medical imports result in measurable increases in deaths among mothers and children. Prenatal care is disrupted by shortages of basic supplies such as sterile gloves, ultrasound gel, and essential drugs like oxytocin. Meanwhile, blocked imports of nutritional supplements and vaccines leave newborns and infants dangerously exposed.

In African settings, where maternal mortality rates are already among the highest in the world, sanctions magnify vulnerabilities. A mother denied access to an emergency C-section due to the absence of anesthesia drugs is not a statistic; she is the unseen casualty of foreign policy decisions made thousands of miles away. Similarly, infants dying of preventable infections due to vaccine delays are victims of geopolitical chess games in which their lives weigh less than diplomatic leverage.

The ripple effects extend to public health programs. Family planning initiatives falter when contraceptives are unavailable; HIV/AIDS prevention stalls when testing kits and antiretrovirals cannot be procured. This collapse is rarely acknowledged in official sanction impact assessments, yet it represents the true human cost of economic restrictions.

5.4 Imports and Blocked Supply Chains

Sanctions are not merely financial penalties; they are logistical blockades. Even when humanitarian exemptions exist, the practical mechanics of global trade often nullify them. Banks over-comply with restrictions, refusing to process payments for goods destined for sanctioned countries, fearing reputational risks or fines. Shipping companies, wary of secondary sanctions, avoid ports associated with sanctioned regimes altogether. Insurance firms, whose coverage is critical for maritime trade, quietly withdraw their services.

The result is a de facto embargo on healthcare-related imports, regardless of whether they are technically exempt. Yazdi-Feyzabadi et al. (2024) show that these barriers create spiraling costs for medical supplies, as African governments are forced to rely on black markets or middlemen who demand exorbitant fees.

Consider the case of diagnostic equipment: even when suppliers are willing to sell, the absence of financial clearing mechanisms forces buyers into barter arrangements or cryptocurrency transactions, both of which are unreliable for national-scale procurement. The collapse of formal import routes drives up prices, reduces supply, and introduces counterfeit or substandard products into the market—further endangering patients.

Food and fuel imports are also entangled in these dynamics. Hospitals cannot function without reliable electricity for surgical theaters or cold storage for vaccines. When sanctions disrupt fuel imports, power outages become routine, jeopardizing patient care. Likewise, when food imports are restricted, malnutrition rates rise, weakening populations and making them more susceptible to disease.

The human consequences of these logistical blockades are often invisible in sanction debates, overshadowed by geopolitical rhetoric. Yet for African SMEs importing medicines, or for rural clinics awaiting vaccine shipments, the impact is devastatingly clear. Sanctions do not stop at government offices; they reach into pharmacies, hospital wards, and ultimately, the lives of ordinary people.

5.5 Sanctions as a Violation of the Right to Health

The right to health is enshrined in multiple international covenants, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Yet sanctions, in practice, often transform this right into an empty promise. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has repeatedly warned that unilateral sanctions undermine access to health services, medicines, and humanitarian aid, thereby amounting to structural violations of human rights (OHCHR & Special Procedures, 2025).

The ethical contradiction is glaring. States imposing sanctions frequently proclaim their commitment to human rights, while their policies directly impede a population’s access to essential health care. The humanitarian exemptions cited in sanction documents often prove illusory, creating what human rights lawyers call the “compliance paradox.” Banks, shippers, and suppliers avoid sanctioned markets altogether, rendering exemptions meaningless.

For African nations, this translates into systemic denial of basic care. The principle of health as a universal right collapses under the weight of geopolitical maneuvering. When children die for lack of polio vaccines, or when hospitals close intensive care units because ventilators cannot be imported, the gap between international law and international practice becomes impossible to ignore.

5.6 African Case Studies: The Silent Wards

To illustrate the human cost, it is necessary to descend from the high language of policy into the silent wards of African hospitals. Consider a West African nation facing sanctions not directly for health-related issues but for alleged governance failures. Despite exemptions, pharmaceutical imports fall by more than 60%. Cancer patients who once received chemotherapy cycles suddenly find themselves rationed to half-doses. HIV/AIDS programs stall as supplies of antiretrovirals dry up.

Maternal health wards offer another tragic window. With imports of anesthetics blocked, obstetricians revert to outdated practices or delay emergency surgeries. Mortality rates rise, not because of medical incompetence, but because the tools of survival have been sanctioned out of reach.

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the healthcare sector also collapse under the weight of these restrictions. Local distributors who once imported diagnostic kits or generic drugs are driven into bankruptcy. The result is a hollowing out of national health systems, as both public and private actors lose the ability to provide care.

These local stories rarely make it into the policy debates of Washington or Brussels. Yet they are the true battlegrounds where sanctions write their human toll.

5.7 Global Comparisons: Lessons from Iran, Cuba, and Beyond

Although this exposé focuses on Africa, the continent’s experience with sanctions is not unique. Iran, Venezuela, and Cuba provide global case studies demonstrating the predictable health consequences of broad economic restrictions.

In Iran, sanctions triggered shortages of chemotherapy drugs and blood-clotting factors, despite supposed humanitarian exemptions. In Cuba, decades of sanctions constrained access to medical technology and created chronic shortages in hospitals. Venezuela’s economic collapse, amplified by sanctions, saw maternal mortality soar and diseases like malaria re-emerge at scale.

These global parallels underline a consistent truth: sanctions rarely achieve their stated political objectives, yet they consistently devastate healthcare systems. Yazdi-Feyzabadi et al. (2024) emphasize that the indirect effects—emigration of medical professionals, degradation of infrastructure, collapse of preventative programs—often dwarf the direct shortages of drugs and supplies.

For African policymakers, the lesson is clear: reliance on global supply chains in a world prone to sanctions makes health systems inherently vulnerable. Building resilient, local pharmaceutical production and diversifying trade partners are not luxuries but necessities for survival in an era of weaponized economics.

5.8 Conclusion: The Silent Weapon in the War of Sanctions

The rhetoric of sanctions is always couched in terms of diplomacy and deterrence. Officials speak of “pressuring regimes,” “modifying behavior,” or “enforcing accountability.” Rarely do they acknowledge that the true frontlines are neonatal wards, oncology clinics, and rural vaccination programs.

Evidence from Africa and beyond reveals that sanctions operate as silent weapons of war against healthcare systems. They block imports of life-saving medicines, paralyze procurement of medical equipment, and drive healthcare SMEs into bankruptcy. They raise maternal and child mortality rates, reverse decades of progress against preventable diseases, and institutionalize health inequality on a global scale (Gibson, 2025; Yazdi-Feyzabadi et al., 2024).

From a human rights perspective, sanctions amount to collective punishment. They punish populations for the political decisions of their leaders, in violation of the principle that no civilian should be denied fundamental rights because of geopolitical disputes (OHCHR & Special Procedures, 2025).

The African experience demonstrates both the fragility and resilience of health systems under siege. Fragility, because the dependence on imports renders countries vulnerable to external pressures. Resilience, because despite these pressures, health workers and communities often find innovative ways to cope—whether through local production of generic drugs, cross-border smuggling of vaccines, or community-based healthcare initiatives.

Yet resilience is not enough. To safeguard healthcare against sanctions, African nations must invest in regional pharmaceutical hubs, develop continental insurance mechanisms to underwrite trade, and push for global reform of sanction regimes. International law must evolve to make the right to health non-negotiable, even in the context of economic warfare.

In the end, the silent victims of sanctions are not governments but patients. The measure of any policy is not its rhetoric but its human impact. By that standard, sanctions on African nations—regardless of their geopolitical justifications—have failed the test of justice.

Part 6: How Sanctions Reshape Trade Routes

When sanctions close doors, commerce does not stop; it reroutes, reshapes, and reinvents itself—often at devastating costs to African economies.

6.1 The Sanction as a Trade Disruptor

Sanctions are rarely discussed in terms of logistics, yet their most visible impact is geographic. When a nation is cut off from mainstream financial systems and major trade corridors, the effect is not simply economic—it is spatial. Entire trade routes are redrawn in response to sanction regimes, altering shipping flows, raising costs, and eroding competitive advantage.

For African nations, the geography of trade is already complex. Landlocked economies depend on corridors through neighboring states; coastal states rely on vulnerable shipping lanes dominated by global giants. When sanctions strike, these fragile routes become unstable. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN/DESA, 2025) highlights how sanctions against South Africa in recent years drove shippers toward less efficient, longer alternative routes, increasing costs and making traditional shipping lanes less viable.

The result is not only higher prices for consumers but also deep structural distortions. Goods that once flowed through established maritime arteries must now take circuitous paths, undermining predictability and choking off regional trade integration.

6.2 Africa’s Position in a Fragmenting Global Trade Map

Sanctions-driven trade disruptions must also be seen in the broader context of global fragmentation. The McKinsey Global Institute (2024) describes how geopolitical rivalries and sanction regimes increasingly redraw the “geometry of global trade.” Instead of a seamless globalized system, trade now clusters into blocs—Western-aligned, China-Russia-aligned, and non-aligned networks where African economies often struggle to find balance.

This fragmentation hits African exporters and importers particularly hard. For instance, when Western sanctions limit transactions with Russia, African countries dependent on Russian fertilizers are forced to reroute through Asian intermediaries, adding time and cost. Conversely, African oil exporters facing Western restrictions may pivot to Asian markets, but lack of direct shipping capacity inflates transport costs.

Sanctions thus impose a “geopolitical tax” on African trade. They force traders into second-best routes, deepen dependency on middlemen, and exacerbate the already-high cost of doing business across the continent.

6.3 The Banking and Shipping Nexus

Trade routes are not only geographical; they are also financial. When sanctions block access to dollar-clearing systems or SWIFT transactions, the impact ripples directly into shipping. African SMEs and larger exporters find themselves unable to insure cargo, book slots on Western-dominated shipping lines, or settle payments in standard currencies.

This financial paralysis has real-world geographic consequences:

- Ships avoid sanctioned ports, forcing rerouting to less equipped harbors.

- Insurance premiums skyrocket, making some routes prohibitively expensive.

- Cargo transits through neutral states, adding logistical steps and delays.

In practice, this turns what was once a three-day maritime route into a two-week odyssey, with costs rising exponentially. The inefficiencies are borne not by the sanctioning powers but by African producers and consumers, who face price spikes in everything from wheat to medical equipment.

6.4 Historical Echoes: From Apartheid South Africa to Modern Sanctions

The idea of sanctions reshaping African trade is not new. During the apartheid era, international sanctions forced South Africa into costly rerouting strategies, relying on shadow shipping networks and alternative financing mechanisms. The echoes of those years resonate today, as sanctions again target South Africa, forcing similar distortions (UN/DESA, 2025).

But unlike the apartheid era, today’s trade networks are more interconnected and digitized. This means that disruptions are faster, wider, and more systemic. A sanction on one node can ripple through entire supply chains, magnifying costs across industries and borders.

For example, sanctions that restrict one country’s ability to export minerals do not only harm that country’s GDP; they disrupt global supply chains for smartphones, electric vehicles, and industrial machinery. In turn, African nations reliant on these supply chains for jobs and growth face indirect punishment.

6.5 Case Studies: Fertilizers, Oil, and Food

The fertilizer trade is one of the most striking examples of sanctions-induced rerouting. Africa is heavily dependent on Russian and Belarusian fertilizers to sustain its agricultural sector. When sanctions cut off direct shipments, importers in Africa were forced to secure fertilizers through intermediaries in Asia and the Middle East. What once was a straightforward transaction became a logistical maze: ships docking in neutral ports, goods repackaged and relabeled, and new trade documentation created to bypass sanction scrutiny.

This not only raised costs by 20–40 percent but also caused delays at the peak of planting seasons, threatening food security across sub-Saharan Africa. Smallholder farmers, who already operate on razor-thin margins, were hit hardest.

Oil markets provide another telling case. When Western sanctions curbed exports from African oil producers tied to Russian refiners or markets, these producers shifted toward Asian buyers. Yet because direct maritime and financial channels were limited, crude often traveled circuitous routes through intermediary hubs like Singapore or Malaysia. The result: reduced profit margins, logistical bottlenecks, and higher shipping insurance costs.

Food imports have also suffered. Wheat from sanctioned suppliers had to be rerouted through third countries, doubling shipping times and raising bread prices in African cities. What is often framed as “targeted sanctions” ends up striking the urban poor in Lagos, Nairobi, and Kinshasa.

6.6 The Rise of Informal and Black-Market Trade Routes

Whenever formal trade collapses, shadow economies rise. Sanctions have birthed an ecosystem of black-market trade routes across Africa. From informal trucking corridors linking sanctioned states to their neighbors, to shadow shipping companies operating under flags of convenience, commerce adapts to survive.

But this adaptation comes at a cost. Informal trade routes rarely offer consumer protections, quality guarantees, or fair prices. Goods often become scarce, adulterated, or exorbitantly priced. Worse still, black-market routes enrich smuggling networks, corrupt officials, and transnational criminal organizations.

The danger for African economies is that once informal routes take root, they are hard to dismantle. Even if sanctions are lifted, the underground trade networks remain, siphoning revenue from governments and embedding corruption into state systems.

6.7 Policy Responses by African Governments

African governments have attempted various responses to mitigate the trade distortions caused by sanctions. Some have pursued diplomatic channels, lobbying sanctioning powers to create exemptions for essential goods such as fertilizers and medicines. Others have sought to strengthen regional integration through blocs like ECOWAS, SADC, and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), hoping to reduce dependency on extra-continental trade flows.

In some cases, governments have invested in alternative corridors, building new ports, roads, and railways to diversify trade options. Yet infrastructure alone cannot solve the deeper problem: Africa’s vulnerability stems from its limited bargaining power in a sanctions-dominated global order.

The most effective responses have come from multilateral efforts to negotiate humanitarian exemptions and carve-outs. However, even these are often slow, bureaucratic, and unevenly applied, leaving many African traders caught between compliance fears and survival imperatives.

6.8 Conclusion: Toward Resilient Trade Architectures

Sanctions have made one thing clear: Africa cannot afford to rely on a single set of trade corridors or financial systems. The cost of rerouting under duress is too high, both economically and socially.

Building resilience will require three shifts:

- Diversification of Trade Partners

African states must broaden their networks, engaging not only with traditional Western partners but also with Asia, Latin America, and intra-African trade. - Regional Self-Sufficiency

Strengthening the AfCFTA, boosting agricultural self-reliance, and investing in continental supply chains will reduce exposure to global shocks. - Alternative Financial Channels

Developing local currency settlements, regional payment systems, and non-dollar trade mechanisms will blunt the force of banking sanctions that paralyze trade routes.

In the end, sanctions reshape trade not only by closing routes but by teaching nations new lessons in resilience. Africa’s task is to convert the pain of rerouting into a blueprint for autonomy.

As McKinsey Global Institute (2024) observed, the new geometry of global trade is not set in stone; it is being redrawn in real time. Africa must seize this moment to inscribe itself onto the map not as a victim of sanctions but as a builder of alternative corridors that serve its own people first.

Read also: The Lost Science Of Ancient Healing

Part 7: The Role of Secondary Sanctions on Neighboring States

How punishment aimed at one nation silently punishes its neighbors, reshaping entire regions.

7.1 The Invisible Reach of Sanctions

Economic sanctions are often described as targeted tools—sharpened instruments of diplomacy designed to wound specific regimes or sectors without harming broader populations. In reality, however, sanctions behave more like shockwaves. They strike the intended target but ripple far beyond borders, destabilizing regional economies and straining diplomatic ties. These unintended effects are particularly severe for neighboring states, which may not be directly sanctioned yet find themselves collateral victims of financial isolation, blocked trade corridors, and political stigma (Chatham House, 2025).

The logic is simple but brutal. Borders in Africa are porous, economies are interlinked, and trade corridors rarely respect the artificial lines drawn on colonial maps. When sanctions cut a sanctioned nation off from global markets, the fallout spills instantly into the economies next door. Trucks halt at borders, ports choke on stranded goods, and small traders—who form the lifeblood of regional commerce—face ruin.

7.2 Secondary Sanctions: The Silent Hand of Enforcement

Beyond direct sanctions, the practice of secondary sanctions magnifies the burden. These measures target third-party countries, companies, or individuals who continue to engage with sanctioned states. Essentially, they force neighbors to choose between loyalty to their regional partners and access to the global financial system.

For African states, this is no choice at all. A landlocked country that relies on a sanctioned neighbor’s ports or pipelines suddenly finds itself trapped. Banks in a non-sanctioned country that process payments on behalf of the targeted nation risk losing access to international financial markets. Even humanitarian agencies attempting to deliver food and medicine hesitate, fearing that their operations might trigger penalties under secondary sanctions (Sage Journals, 2023).

This coercive spillover effect transforms sanctions into a weapon not just against the intended regime, but against entire regions whose only crime is proximity.

7.3 Sudan: A Case Study in Regional Pain

The long years of sanctions on Sudan illustrate the phenomenon vividly. Officially, sanctions were directed at Khartoum’s leadership, accused of harboring terrorism and committing atrocities. In practice, however, Sudan’s neighbors bore significant costs.

Countries like South Sudan, Chad, and Ethiopia, which depended on cross-border trade and remittance flows, found themselves ensnared. Goods that once flowed easily across borders slowed to a trickle. Informal markets adapted, but at a steep price: higher costs for consumers, reduced revenues for governments, and increased reliance on smuggling networks.

The Journal of Peace Research observed that Sudanese public suffering persisted long after some sanctions were formally lifted, in part because regional economies had already restructured around scarcity and informality (Sage Journals, 2023). Neighboring states paid a price not just in lost trade but in heightened insecurity, as smuggling routes overlapped with arms trafficking and insurgent networks.

7.4 The Banking Trap

One of the most devastating impacts of secondary sanctions is financial isolation. Even when trade routes remain physically open, banking channels are not. African banks in countries not under sanction often “de-risk”—cutting off any ties, however small, to avoid triggering secondary sanctions themselves.

This retreat paralyzes small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that rely on cross-border payments. For example, a textile exporter in Ethiopia who once shipped goods through Sudan suddenly finds invoices unpaid because her bank refuses to process transactions linked to Sudanese counterparts. A Ghanaian construction firm contracted in a sanctioned state sees its payments frozen mid-project.

Chatham House (2025) has highlighted how this climate of financial fear undermines entire regional blocs, eroding trust between states and leaving local businesses hostage to geopolitical rivalries.

7.5 Humanitarian Consequences in Neighboring States

Secondary sanctions do not simply choke banks and block goods—they ripple into the very core of human survival. When a sanctioned nation’s economy collapses, the spillover quickly overwhelms neighboring states that host refugees, share health systems, or depend on cross-border food supply chains.

For instance, during years of sanctions on Sudan, neighboring Chad and South Sudan saw waves of displaced families crossing borders in search of food, medicine, and basic security. Local clinics and schools—already underfunded—buckled under the strain. Humanitarian agencies operating in the region often faced near-impossible dilemmas: deliver aid that risked violating sanctions or withhold lifesaving supplies to remain compliant with international regulations.

Chatham House (2025) stresses that secondary sanctions, though rarely acknowledged in official rhetoric, create “a humanitarian chokehold” on populations in neighboring states. This means that while policymakers in Washington, Brussels, or London may frame sanctions as precise diplomatic tools, the lived experience in Africa is closer to collective punishment.

7.6 Diplomatic Tightropes: Balancing Global and Regional Interests

African governments caught in the web of secondary sanctions must navigate an impossible balancing act. On one side lies the need to maintain cordial relations with the sanctioned neighbor, often tied to shared culture, history, and critical infrastructure. On the other side lies the immense pressure to comply with Western powers who dominate the global financial system.

This tension has produced a paradoxical diplomacy. Publicly, African leaders may condemn sanctions as unjust and harmful to ordinary citizens. Privately, they instruct their central banks and commercial institutions to sever even the faintest ties with sanctioned nations. The result is a deep erosion of regional solidarity.

In the Horn of Africa, for example, Ethiopia has often had to walk this diplomatic tightrope. While sharing extensive economic and cultural links with Sudan, it has simultaneously curtailed financial transactions to avoid triggering secondary sanctions. This posture strains regional organizations like the African Union and IGAD, which aspire to collective approaches but are undermined by the asymmetry of global financial coercion.

7.7 Policy Responses: How Neighbors Adapt or Resist

Despite the suffocating reach of secondary sanctions, African neighbors have not remained passive. Some adopt creative adaptation strategies, while others quietly resist.

Adaptation often takes the form of informal economies. Traders reroute goods through clandestine channels, creating black markets that enrich middlemen while depriving states of tax revenues. Cross-border communities fall back on barter systems or cash economies, bypassing frozen banking channels. This adaptation ensures survival but fosters lawlessness and undermines long-term development.

Resistance, on the other hand, emerges in diplomatic forums. Regional blocs such as ECOWAS and SADC have periodically called for the reconsideration of broad sanctions regimes, emphasizing their disproportionate impact on uninvolved states. However, these calls often collide with the geopolitical interests of powerful sanctioning nations.

Scholars note that some African governments deliberately pursue “quiet defiance,” maintaining minimal humanitarian or trade contact with sanctioned states in ways that avoid global attention. This strategy preserves lifelines without provoking outright retaliation, but it also underscores the precariousness of sovereignty under global sanctions regimes (Sage Journals, 2023).

7.8 Conclusion: Collateral Damage or Strategic Leverage?

Secondary sanctions expose a hard truth about the global order: the pain of punishment rarely respects borders. They transform targeted economic weapons into regional crises, punishing innocent neighbors who never stood trial in the court of international diplomacy.

From Sudan’s sanctions era to current cases elsewhere in Africa, the pattern is clear. Banks retreat, trade collapses, refugees flee, and neighboring states—already fragile—are dragged into spirals of instability. Chatham House (2025) rightly observes that if sanctions are to remain part of the international toolkit, they must be recalibrated to prevent such disproportionate collateral damage.

The question, however, is whether this collateral damage is merely an accident—or whether it serves as deliberate leverage. By allowing secondary sanctions to pressure neighboring states, sanctioning powers amplify their reach, forcing entire regions to isolate the target. In this light, collateral damage becomes not just a side-effect but part of the strategy.

For Africa, the path forward lies in building financial and political resilience. Regional payment systems, stronger intra-African trade routes, and united diplomatic stances could blunt the sharp edges of secondary sanctions. Without such measures, African states will remain vulnerable to punishment not for their actions, but for their geography.

Part 8: Sanctions Evasion Tactics and Black Markets

How the shadows of global finance create survival routes for sanctioned states and lifelines for authoritarian regimes.

8.1 The Shadow Economy as Counter-Sanctions

Economic sanctions are often framed as the “clean weapon” of modern statecraft — bloodless tools that can cripple economies without the optics of war. Yet, history has shown that every sanction spawns its countermeasure, and every block creates its bypass. What emerges is not compliance, but adaptation: shadow markets, covert finance networks, and the normalization of evasion.

As Johnstone et al. (2025) observe in their work for the Hoover Institution, the Global Sanctions Database has repeatedly demonstrated how sanctioned states reconfigure their economies through black markets, clandestine banking, and proxy trade routes. The lesson is simple: sanctions intended to suffocate often end up fostering new, hidden circulatory systems that keep targeted regimes alive — and sometimes even more insulated.

8.2 Dubai: The Global Junction of Illicit Evasion

Perhaps nowhere is this clearer than in Dubai. Long celebrated as a hub for global finance and logistics, the city has also become a nucleus of sanctions evasion. Krylova (2023) documents how Dubai functions as a safe haven for covert gold trading, shell companies, and crypto-enabled evasion schemes that serve sanctioned actors from Africa, Russia, and beyond.

Gold, in particular, has become the perfect instrument for sanctions evasion: portable, easily laundered, and resistant to traceability. In Dubai’s bustling souks, tons of African gold — often mined under brutal conditions — are funneled into global markets, bypassing restrictions on sanctioned governments. Crypto adds a new dimension: transactions disappear into blockchain anonymity, while the emirate’s permissive regulatory environment allows such flows to move without serious oversight.

What sanctions choke in the open, Dubai’s shadows resuscitate.

8.3 Tax Havens: Sanctuaries for Sanctioned Wealth

A second layer of evasion resides offshore. Kavakli, Marcolongo, & Zambiasi (2023) show convincingly how tax havens provide shelter for sanctioned elites’ assets. From shell corporations in the British Virgin Islands to accounts in Swiss or Caribbean jurisdictions, sanctioned actors have long relied on secrecy havens to store wealth safely beyond the grasp of regulators.

This system thrives not only because of weak enforcement but also because powerful Western interests benefit from it. Lawyers, bankers, and corporate service firms in London, New York, and Zurich quietly profit from keeping sanctioned capital alive under new disguises. Thus, while policymakers in Washington and Brussels trumpet sanctions as hard-line tools, their own financial ecosystems serve as complicit enablers of the very actors they claim to isolate.

8.4 Military Goods and the Transshipment Maze