An Investigative Series by Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

Investigative Journalist | Public Intellectual | Global Governance Analyst | Health & Social Care Expert

Editorial Statement

In a world where modern medicine often parades itself as the final word on human health, The Lost Science of Ancient Healing delivers a stunning reminder: the foundations of medicine were laid long before the pharmaceutical age, and much of that wisdom was deliberately buried. From Africa’s vast pharmacopeias and India’s Ayurvedic blueprints to Chinese cosmological medicine and Indigenous traditions across the globe, our ancestors charted intricate systems of healing that fused the body, mind, spirit, and environment into a holistic science of life.

This series is more than a historical recovery; it is an exposé of how empire, patriarchy, and corporate capitalism waged war on these sciences. Colonizers criminalized African herbalists, demonized women healers as witches, and erased indigenous psychiatric traditions, even as they quietly looted cures for their own profit. The rise of pharmaceutical empires turned health into a market commodity, burying preventive knowledge while profiting from chronic disease.

Yet history has a way of resurfacing. Today, as chronic illness, ecological collapse, and health inequities deepen, the world is rediscovering what was long dismissed as superstition. From WHO initiatives to grassroots revivals, Ayurveda, Traditional Chinese Medicine, and African healing traditions are regaining legitimacy, often corroborated by cutting-edge science.

The Lost Science of Ancient Healing is not nostalgia—it is a manifesto for the future of medicine. It calls for a radical decolonization of health, restoring indigenous knowledge to its rightful place alongside biomedical science. In doing so, it offers a vision of healthcare beyond the pill: preventive, ecological, pluralistic, and rooted in the wisdom of humanity’s deepest traditions. This series is not just about healing the past—it is about reclaiming the future.

— The Editorial Board

People & Polity Inc., New York

Executive Summary

Reclaiming ancient wisdom for a healthier future

The Lost Science of Ancient Healing unearths a forgotten intellectual inheritance: the medical sciences cultivated by ancient civilizations long before the rise of modern biomedicine. Across continents and centuries, Egypt, India, China, Africa, and Indigenous societies developed intricate frameworks of health that combined careful observation, empirical practice, and spiritual insight. These traditions embraced a holistic understanding of the body, mind, spirit, and environment, anticipating many principles that contemporary science is only beginning to rediscover.

Food was medicine, not commodity. Fasting, grains, and sacred diets functioned as preventive therapies, sustaining microbiomes and balancing bodily rhythms. Plants were pharmacological treasures; their healing compounds refined through generations of use and reverence. Energy was mapped as qi, prana, and vital force, interwoven with cosmic rhythms, sound, and vibration, forming early sciences of bioenergetics. Cleansing rituals—sweating, steaming, purging—embodied detoxification long before biomedical toxicology emerged. Mental and spiritual healing was pursued through meditation, prayer, dream interpretation, and shamanic practice, establishing psychiatric sciences that integrated psychology, ritual, and community.

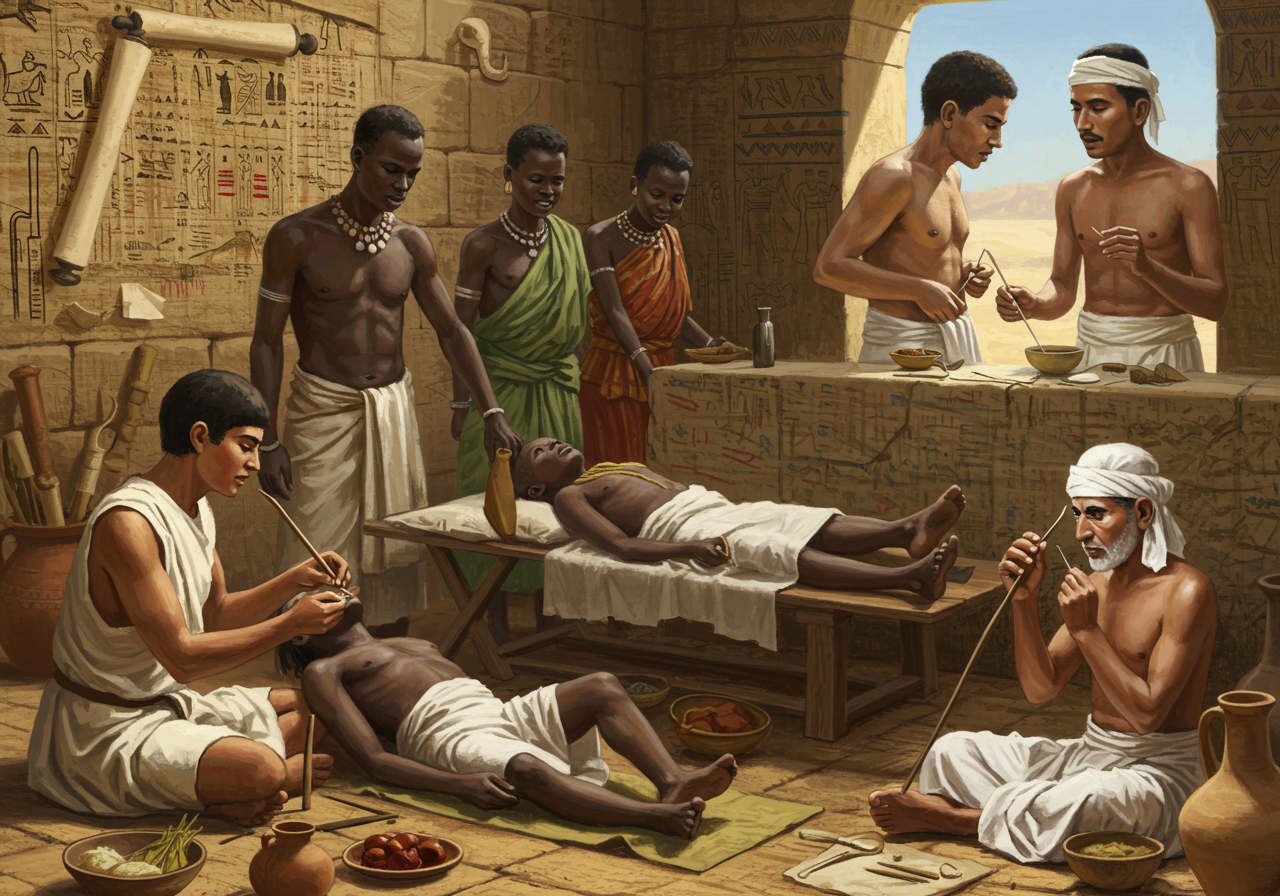

Surgical innovations reveal extraordinary skill: trepanation with documented survival, cataract operations in India, and dental interventions in Egypt. Women, as midwives, herbalists, and priestesses, carried healing knowledge across generations, only to be criminalized and erased under patriarchal medicine. Colonial expansion deepened these erasures, suppressing indigenous healers, appropriating remedies, and instituting segregated medical systems that entrenched racial hierarchies. The rise of capitalism and corporate health industries further marginalized preventive traditions, commodifying treatment while profiting from chronic disease.

Yet today, a global reawakening is underway. Traditional systems such as Ayurveda, Chinese medicine, and African herbalism are regaining legitimacy, supported by WHO initiatives, grassroots revival, and scientific validation. This movement signals a paradigm shift: from narrow pharmaceutical dependence toward integrative, preventive, and ecological models of health. Protecting indigenous intellectual property and building pluralistic healthcare frameworks are essential steps in this transition.

This work reveals that the so-called “lost” sciences were never lost at all—they were concealed, suppressed, and overlooked. To reclaim them is to embrace a future of medicine beyond the pill, where ancient wisdom and modern science converge to create a planetary health system rooted in prevention, ecology, and holistic well-being.

Part 1 — Forgotten Blueprints of Wellness

How ancient civilizations mapped healing systems long before modern medicine

1.0 Introduction: Rediscovering the Medical Past

The story of medicine did not begin with the advent of modern biomedicine but was shaped by thousands of years of trial, error, intuition, and cultural systems of healing. From Egypt to India, from China to Africa and the Americas, early civilizations designed sophisticated frameworks for health that integrated the body, mind, spirit, and environment. These frameworks were not incidental folklore but structured blueprints of wellness grounded in observation and experience (Elendu, 2024). Today, as modern science increasingly acknowledges the value of traditional and complementary medicine, the task of rediscovering these blueprints becomes more urgent—not as nostalgic curiosity, but as a resource for reshaping a holistic and preventive model of healthcare.

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2023) estimates that 80% of the global population relies on traditional medicine for primary care. This reliance is not a remnant of a pre-scientific age but a testament to its continuing efficacy and adaptability. Yet, despite their significance, these ancient systems were often marginalized, dismissed, or actively suppressed during the rise of Western biomedicine. As Dwivedi (2023) and Ouma (2022) show, the mapping and documentation of these practices reveal both their resilience and the intergenerational knowledge transfers that kept them alive even under colonial and postcolonial disruptions.

This chapter traces the forgotten blueprints of wellness—how ancient civilizations conceptualized health, mapped healing codes, used plants as proto-pharmaceuticals, and how these legacies were obscured by colonial medicine. The goal is to unearth what history concealed and to situate traditional knowledge as a critical partner, rather than an outdated relic, in contemporary medicine.

1.1 The Holistic View of Body, Mind, and Spirit

A defining feature of ancient healing systems is the holistic view of health, one that resists the dualism of mind and body characteristic of modern Western medicine. Marques (2021) explains that many indigenous cultures embedded healing in the broader cosmological order—health was not merely the absence of disease but the equilibrium of physical, emotional, spiritual, and ecological relationships.

For example, Chinese medicine’s yin-yang theory and India’s Ayurveda emphasize balance, interconnectedness, and lifestyle practices for preventive health. Similarly, African and Indigenous American traditions view illness as disharmony between the individual, community, and environment. Turner (2025) illustrates how the Philippines’ traditional cartographies of healing situate wellness in relation to ancestral heritage, sacred landscapes, and communal practices. Such systems framed health not as an isolated biological event but as an ecosystemic balance—an approach that resonates with modern ecological and psychosomatic medicine.

Dwivedi (2023) shows that holistic views were passed down through oral traditions, with healers, shamans, midwives, and elders acting as custodians of integrated knowledge. This intergenerational transmission, as Ouma (2022) highlights in the Kenyan context, underscores that healing was both a science and a cultural pedagogy, where rituals, herbal pharmacology, and spiritual practices converged to sustain collective wellbeing.

1.2 The Egyptian, Chinese, and Indian Healing Codes

Egyptian, Chinese, and Indian civilizations produced codified systems of medicine that reveal remarkable sophistication. Egyptian papyri detail surgical procedures, diagnostics, and herbal remedies, while Indian texts like the Charaka Samhita and Sushruta Samhita codified anatomy, surgery, and preventive care. Chinese classics, such as the Huangdi Neijing, elaborated on meridians, qi, and seasonal rhythms as determinants of health (Elendu, 2024).

Graz and Itrat (2022) trace how Unani medicine—originating in Greco-Arabic traditions but deeply influenced by Indian and Persian thought—was transplanted to the West and continues to shape integrative approaches. These codes were not mystical conjectures but early scientific enterprises, guided by rigorous observation and classification. Ang (2024), in a systematic mapping of evidence on traditional medicine, demonstrates how many of these frameworks continue to provide therapeutic value, from chronic disease management to preventive healthcare.

Potenza (2023) underscores this with the example of Panax ginseng, a plant revered for millennia in East Asia. Modern pharmacological studies confirm its adaptogenic properties, validating the experiential wisdom of Chinese medical codes. Such continuity between ancient prescriptions and contemporary scientific findings challenges the dichotomy between “traditional” and “scientific” medicine.

1.3 Herbalism as Proto-Pharmacology

Herbalism represents one of the clearest continuities between ancient healing and modern pharmacology. Potenza’s (2023) account of Panax ginseng illustrates how early civilizations identified, classified, and refined herbal remedies as therapeutic agents. Herbal pharmacopeias were not mere folklore—they involved experimental methods, dosage regulation, and long-term observation, amounting to proto-pharmacology.

Eruaga (2024) observes that in contexts like Nigeria, herbal medicine continues to evolve, with debates around regulation, standardization, and integration into modern systems. This tension underscores both the resilience and vulnerability of herbalism in contemporary health landscapes. Turner (2025) adds that indigenous pharmacopeias are also cultural archives, encoding ecological knowledge, seasonal cycles, and cosmological significance.

WHO (2023) affirms the enduring relevance of herbal medicine by advocating for its integration into universal health coverage. Ang (2024) further highlights how evidence maps show increasing clinical validation of herbal remedies for conditions ranging from metabolic disorders to mental health. Thus, herbalism must be recognized as the earliest form of systematic pharmacological research, bridging empirical science with cultural frameworks.

1.4 The Marginalization of Ancient Knowledge during Colonial Medicine

Despite their resilience, these ancient systems were systematically marginalized during the colonial encounter. Western medicine, aligned with imperial projects, constructed indigenous practices as “superstition” or “quackery.” This epistemic violence delegitimized local healers and imposed biomedical dominance (Elendu, 2024).

Graz and Itrat (2022) highlight how Unani and Ayurvedic systems were suppressed under colonial regimes, even as colonial scientists selectively appropriated certain remedies for European pharmacopoeias. Ouma (2022) notes how intergenerational learning of healing knowledge in Africa was disrupted by missionary schools and colonial hospitals that stigmatized traditional practices. The colonial project thus not only disrupted cultural knowledge but also restructured healthcare systems to serve extractive and racialized hierarchies.

Eruaga (2024) observes that regulatory frameworks in postcolonial contexts often continue this legacy, privileging biomedical authority while restricting indigenous practices. This marginalization is not merely historical but a contemporary issue, as indigenous healers struggle for recognition, resources, and legitimacy within formal healthcare systems.

1.5 Conclusion: What History Concealed

The blueprints of ancient healing, far from being obsolete, embody a holistic, preventive, and integrative vision of health that modern medicine increasingly rediscovers. From the Egyptian papyri to Ayurveda and Chinese medicine, from African pharmacopeias to Filipino healing cartographies, these traditions represent humanity’s first scientific inquiries into wellness. They anticipated modern concepts of balance, psychosomatic health, pharmacology, and ecological interdependence.

What history concealed, through colonial suppression and biomedical hegemony, was the scientific and cultural legitimacy of these systems. Yet, as WHO (2023) emphasizes, traditional medicine remains indispensable to billions worldwide. Rediscovering these blueprints does not mean romanticizing the past but recognizing the plurality of medical epistemologies and restoring what colonial and modernist narratives erased.

As Dwivedi (2023) and Ouma (2022) show, these systems survive through intergenerational knowledge and adaptive resilience. Today, the challenge is not only to document and validate these practices but to integrate them into a pluralistic, planetary health paradigm—one that bridges the wisdom of the ancients with the rigor of modern science.

Part 2 — Roots and Remedies

The pharmacological wealth hidden in plants and natural compounds

2.0 Introduction: Nature as the First Pharmacy

Long before laboratories and synthetic compounds, humanity turned to nature as its first and most enduring pharmacy. Plants, minerals, and animal products provided the pharmacological wealth upon which survival depended. Across civilizations, sacred plants were revered not only for their curative properties but also for their spiritual and symbolic significance. This chapter examines the pharmacopeias of the Nile and Indus valleys, indigenous African herbal traditions, the colonial silencing of herbalism, and its rediscovery in modern pharmacology. The enduring importance of nature as a pharmacopeia is underscored by contemporary studies that validate the medicinal efficacy of ancient herbal remedies (Mustafa, 2025; Metwaly, 2021).

2.1 Sacred Plants of the Nile and Indus Valleys

In ancient Egypt, medicine was inseparable from religion, and plants were imbued with both therapeutic and sacred value. Metwaly (2021) reviews evidence of ancient Egyptian medicinal practices, highlighting herbs such as aloe, garlic, and juniper, which were applied for infections, digestion, and embalming. The Ebers Papyrus, one of the oldest medical texts, documents over 850 plant-based remedies, positioning Egypt as one of the earliest hubs of pharmacological knowledge.

The Indus Valley Civilization, similarly, cultivated a complex herbal tradition that fed into the Ayurvedic system. Rizvi (2022) notes that Indian healing drew on plants like turmeric, neem, and ashwagandha, which served as both household remedies and spiritual agents. Their enduring use across centuries speaks to the stability and adaptability of this ancient pharmacological base.

Mustafa (2025) illustrates how coumarins, natural compounds found in various plants, represent an example of how phytochemistry bridges ancient herbalism and modern drug discovery. Compounds once revered for their healing powers are now understood in terms of molecular pathways, demonstrating continuity across time.

2.2 Indigenous African Pharmacopeias

Africa, often marginalized in historical narratives of science, holds a vast and underexplored pharmacopeia. Ouma (2022) shows that medicinal knowledge in African communities was transmitted intergenerationally, weaving ecological, spiritual, and therapeutic wisdom. Healing plants were not simply medicines but symbols of lineage, ritual, and communal continuity.

Eruaga (2024) highlights the case of Nigeria, where herbal practices continue to thrive, though often relegated to informal healthcare. Plants such as bitter leaf, hibiscus, and moringa serve both as food and medicine, embodying the duality of sustenance and healing. However, regulatory struggles persist, reflecting tensions between biomedical hegemony and indigenous autonomy.

Turner (2025) extends this perspective by mapping Filipino indigenous medicine as part of a broader Southeast Asian healing tradition, showing cross-cultural resonances with African pharmacopeias. These traditions highlight the global diffusion of plant knowledge, which developed not in isolation but through trade, migration, and shared cosmologies.

2.3 The Silencing of Traditional Herbalism by Western Medicine

The colonial encounter marked a turning point in the valuation of indigenous pharmacopeias. Metwaly (2021) notes how colonial medicine in Egypt sidelined traditional herbalism in favor of imported biomedicine, despite the enduring use of herbs among the population. Rizvi (2022) echoes this in India, where colonial powers undermined Ayurveda’s plant-based pharmacopeia while selectively appropriating plants of economic interest, such as opium and quinine.

The process was not limited to knowledge suppression but extended to cultural stigmatization. As Graz and Itrat (2022) document in their exploration of Unani medicine in the West, colonial frameworks cast herbalism as primitive, relegating it to the margins of legitimacy. Ouma (2022) shows how in Africa, intergenerational transmission of herbal knowledge was disrupted by missionary education and the dominance of Western hospitals.

This silencing was not absolute, however. Mustafa (2025) reminds us that certain plant compounds were too powerful to ignore, finding their way into European pharmacopeias. The irony is that the same colonial regimes that disparaged traditional systems simultaneously exploited their pharmacological resources.

2.4 Rediscovery in Modern Pharmacology

The late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen a revival of interest in traditional herbalism, not as nostalgia but as a resource for biomedical innovation. Ang (2024), in an evidence map of traditional medicine, shows how clinical validation of herbal therapies has expanded across a range of conditions, from metabolic syndromes to mental health.

Singh (2024) explores how Chinese medicine, with its rich pharmacopeia of herbs, continues to inform integrative health systems globally. Turmeric’s anti-inflammatory properties, once embedded in Ayurveda, are now part of mainstream nutritional science. Panax ginseng, revered for centuries, has become a global supplement industry (Potenza, 2023).

The rediscovery is also geopolitical. Times of India (2025) notes that India’s holistic wisdom is increasingly shaping Western wellness culture, with Ayurvedic herbs gaining global prominence. Similarly, NCFH (2022) documents how Mayan herbal traditions are resurfacing in North America, carried by migrant communities and revitalized by new generations.

Eruaga (2024) emphasizes that regulation remains critical: without frameworks to protect indigenous knowledge and ensure safety, the revival risks appropriation and exploitation. Yet, as Rizvi (2022) emphasizes, integration of herbalism with biomedical standards may transform healthcare toward more preventive, accessible, and culturally sensitive models.

2.5 Conclusion: Medicines Buried in Plain Sight

The pharmacological wealth hidden in plants has always been in plain sight, yet historical processes of colonialism and biomedical dominance obscured their legitimacy. From the sacred pharmacopeias of Egypt and India to the indigenous traditions of Africa and the Americas, herbalism provided the foundations of medicine. What colonial regimes dismissed as superstition, modern pharmacology increasingly validates as scientific.

Today, as Mustafa (2025), Ang (2024), and WHO (2023) stress, the challenge lies in integrating these ancient pharmacopeias into contemporary health systems while respecting their cultural roots. Rediscovery must not be an act of appropriation but one of restoration, acknowledging the custodians of herbal knowledge and ensuring its ethical use.

In reclaiming medicines buried in plain sight, we are reminded that the future of healthcare lies not only in laboratories but also in the ancient forests, fields, and communities that first charted humanity’s path to healing.

Part 3 — Energy, Rhythm, and the Body

How ancient medicine understood the body through flows of energy

3.0 Introduction: Beyond Anatomy

The history of medicine is not merely the history of anatomy and physiology. Long before microscopes revealed cells or stethoscopes amplified heartbeats, ancient civilizations perceived the body as a vessel animated by invisible forces, rhythms, and energies. These energies—known variously as qi in China, prana in India, ashe in Africa, and vital force in Europe—were central to healing systems across the globe. While often dismissed by modern biomedicine as unscientific, these concepts are now increasingly re-examined by researchers interested in biofields, circadian rhythms, vibrational therapies, and psychoneuroimmunology (Belal et al., 2023; Vijayakumar et al., 2024).

The following sections explore how ancient traditions conceptualized energy and rhythm, how they incorporated cosmological cycles into medicine, and how sound, vibration, and chant were used therapeutically. It also examines modern scientific attempts to measure life energy, revealing a growing convergence between ancient insights and contemporary research. This chapter demonstrates that the dismissal of these traditions as “mystical” was premature, and that the reawakening of energy-based medicine may reshape the future of integrative healthcare.

3.1 Qi, Prana, and Vital Force Traditions

The Chinese concept of qi (life energy) and the Indian idea of prana both express the notion that health depends on the free flow of vital energy through the body. These ideas were not isolated but echoed globally. In West African Yoruba traditions, ashe denotes the spiritual force animating existence, while in European vitalism, élan vital served as a similar principle.

Belal et al. (2023) conducted a qualitative meta-synthesis on the perception of prana during biofield practices, showing that individuals consistently reported sensations of warmth, flow, tingling, and interconnectedness. These experiences, long noted in yoga and qigong, suggest a phenomenological continuity that modern science cannot dismiss as coincidence. Instead, they reflect patterned bodily responses to intentional focus, breath control, and movement.

Vijayakumar et al. (2024) extended this inquiry through a randomized placebo-controlled trial measuring the “time to sense biofield (prana)” between the hands. Their findings indicate that even when controlled for expectancy effects, participants could detect subtle energetic sensations, lending empirical credibility to ancient models of pranic flow.

Such research highlights what Marques (2021) argued in the context of therapeutic environments: that ancient healing values and beliefs about energy are not merely symbolic but are embodied practices that shape physiological and psychological states. As modern neuroscience explores the role of vagal tone, bioelectric signaling, and electromagnetic fields in regulating health, the ancient frameworks of qi, prana, and vital force may be seen less as mysticism and more as early hypotheses about bioenergetics.

3.2 Rhythms of the Moon, Sun, and Body Cycles

Ancient healers also mapped the body in relation to celestial and terrestrial rhythms. In Ayurveda, the doshas (vata, pitta, kapha) are not fixed but fluctuate according to diurnal, lunar, and seasonal cycles. Chinese medicine similarly aligns organ systems with time cycles and seasonal energies, prescribing treatments in harmony with cosmic rhythms.

Shantakumari et al. (2023) review whole-body vibration therapy as a modern analog to these ancient practices, demonstrating how oscillations and rhythmic exposures influence muscle activity, hormonal regulation, and even cognitive functions. This underscores the physiological importance of rhythm in maintaining balance.

Reinhard (2021), reporting on vibration therapy in multiple sclerosis patients, shows that rhythmic interventions can reduce symptoms and enhance well-being. These findings recall ancient practices where healers prescribed rituals aligned with lunar cycles or seasonal fasting, recognizing rhythm as medicine long before circadian biology confirmed it.

The recognition of chronobiology today—the scientific study of biological rhythms—confirms that ancient systems were intuitively correct. Mossière (2025) shows how energy-based practices, especially ritual somatic methods, embody a rhythmic synchronization of body and cosmos. This suggests that the healing systems of old were in fact ecological sciences of rhythm, anticipating the discoveries of melatonin cycles, hormonal tides, and sleep-wake regulation.

3.3 Sound, Chant, and Vibrational Therapy

Sound was central to healing rituals worldwide. Chants, drumming, hymns, and mantras were more than artistic expressions—they were vibrational therapies designed to alter consciousness and promote healing. Bartel (2021) reviews the possible mechanisms by which sound vibrations affect human physiology, noting their impact on neural oscillations, vagal activity, and immune modulation.

Naragatti (2025) expands this perspective, framing the self as part of a universal vibration. His comprehensive review situates chanting, drumming, and mantra recitation as practices that entrain both individual physiology and collective resonance. From Gregorian chants in medieval Europe to Vedic mantras in India, sound was medicine for both body and spirit.

Revival Mental Health (2025) outlines how vibrational healing is being adapted into contemporary integrative practice, highlighting the therapeutic uses of tuning forks, crystal bowls, and vocal toning. These are not inventions of modern wellness culture but revivals of ancient modalities, now supported by growing research into vibrational frequencies and biofield coherence.

Van Heuvelen et al. (2021) provide guidelines for studying whole-body vibration, reflecting a scientific effort to standardize research in a field long dominated by anecdotal evidence. Their work demonstrates that even “vibrational medicine,” once marginalized, is now entering mainstream inquiry.

3.4 Scientific Attempts to Measure “Life Energy”

One of the most contested questions in energy medicine is whether “life energy” can be objectively measured. Early attempts in the 20th century, often dismissed as pseudoscience, are now giving way to more rigorous approaches.

Vijayakumar et al. (2024) provide controlled evidence that subjective experiences of prana are reproducible under experimental conditions. Belal et al. (2023) reinforce this by showing consistent phenomenological accounts of biofield experiences across diverse practitioners. Mossière (2025) suggests that ritual somatic practices may function as embodied technologies of energy transmission, which can be studied in terms of physiology and affective neuroscience.

Academic interest in energy medicine is increasing, with ongoing discussion reflecting both critical perspectives and new supporting evidence. The challenge, as Bartel (2021) notes, lies in developing tools sensitive enough to measure biofields without collapsing them into conventional biomedical categories.

Reinhard (2021) and Shantakumari et al. (2023) provide evidence that vibrational interventions, even when not framed as “energy medicine,” yield measurable effects. This suggests that what ancient healers called qi or prana may correspond to complex interactions of neurophysiology, bioelectrics, and psychosocial factors—an integrative field still in its infancy.

3.5 Conclusion: From Dismissed Mysticism to Measurable Phenomena

Energy and rhythm were once dismissed as the superstitions of pre-scientific cultures. Yet, as modern research continues to validate their physiological, psychological, and therapeutic impacts, it becomes clear that these were not mystical illusions but proto-scientific frameworks for understanding health.

Qi, prana, and vital force traditions offered models of bioenergetics that resonate with modern discoveries in biofields and psychoneuroimmunology. Rhythmic practices aligned the body with lunar, solar, and circadian cycles—ideas now confirmed by chronobiology. Chant, sound, and vibrational therapies, once relegated to alternative medicine, are increasingly supported by evidence showing their impact on neural coherence, vagal tone, and emotional regulation.

As Belal et al. (2023), Vijayakumar et al. (2024), and Mossière (2025) demonstrate, the line between mysticism and science is becoming less rigid. The task is not to romanticize the past but to acknowledge that ancient systems offered testable hypotheses, many of which are only now being confirmed. What was once concealed under the label of superstition may in fact hold keys to a new integrative medicine that honors rhythm, vibration, and the vital energy of life.

Read also: Cancer Prevention Secrets Buried By Corporate Interest

Part 4 — Sacred Diets and Preventive Wisdom

How food was revered as medicine long before pharmaceuticals

4.0 Introduction: The Table as a Temple

Across ancient civilizations, food was never regarded as a mere source of sustenance—it was medicine, ritual, and moral order. Long before the pharmaceutical revolution, societies treated the table as a sacred space where preventive wisdom was enacted daily. Egyptian priests prescribed grain-based diets, Ayurvedic sages aligned foods with the doshas, and Greek physicians proclaimed, “Let food be thy medicine.” In cultures across Africa, Asia, and the Americas, fasting, ritual feasting, and dietary laws reinforced not just physical health but social and spiritual balance.

Today, as the science of nutrition converges with microbiome research and preventive medicine, it is increasingly evident that ancient societies anticipated insights now considered cutting-edge (Goyal & Chauhan, 2024; Wang & Hu, 2022; Rinninella et al., 2023). This chapter examines the preventive power of ancient diets, the role of fasting traditions, the politics of food in suppressing dietary cures, and the modern rediscovery of the gut microbiome. By drawing on contemporary research (Mujica-Parodi et al., 2020; Longo & Mattson, 2021; Alissa & Ferns, 2022; Hosseini et al., 2023; Swanson et al., 2021; Peters et al., 2021; Fleming et al., 2022), we can situate food not only as sustenance but as preventive pharmacology.

4.1 Ancient Grain Diets and Disease Prevention

Grains such as barley, millet, wheat, and rice were staples of ancient diets, revered not only for nourishment but for their preventive health properties. Fleming et al. (2022) demonstrate how Mediterranean and heritage diets rich in grains contributed to longevity and reduced chronic illness. These findings resonate with ancient Egyptian diets centered on barley and emmer wheat, which offered both sustenance and resilience against famine.

Hosseini et al. (2023), in an umbrella review of meta-analyses, confirm that whole grains significantly reduce risks of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity. This validates the millennia-old dietary wisdom embedded in agrarian civilizations. Rinninella et al. (2023) emphasize the systemic benefits of grain-based diets, linking them to gut microbiome diversity—a perspective that echoes Ayurvedic recognition of grains as foundational to digestive fire (agni).

Swanson et al. (2021) expand this insight by examining diet’s role in shaping microbiota, noting that ancient dietary practices inadvertently fostered symbiotic microbial health long before the science of microbiomes emerged. In this sense, ancient dietary codes served as preventive medicine on a microbial as well as cultural scale.

Goyal and Chauhan (2024) add that holistic frameworks of nutrients in traditional medicine emphasized grains as preventive staples, integrating them with herbs, spices, and oils to form balanced diets. Their work illustrates how traditional natural medicine treated grains as pharmacological agents with synergistic properties.

4.2 Fasting Traditions Across Cultures

Fasting has been central to health and spirituality across civilizations. From Christian Lent to Islamic Ramadan, Hindu upavasa, and Indigenous North American vision quests, fasting was recognized as a means to purify body and spirit. Longo and Mattson (2021) review molecular mechanisms of fasting, showing benefits such as autophagy, improved insulin sensitivity, and cellular repair. This demonstrates that what was once a religious obligation also served profound medical functions.

Peters et al. (2021) assess fasting’s impact through human studies, confirming its benefits for weight regulation, metabolic health, and inflammation reduction. These findings echo ancient recognition of fasting as preventive medicine. Wang and Hu (2022) argue that fasting aligns with precision nutrition by synchronizing body systems with circadian rhythms, echoing traditional practices of aligning meals with daylight cycles.

Mujica-Parodi et al. (2020) show that dietary interventions, including intermittent fasting, stabilize brain networks and reduce aging biomarkers. Thus, fasting traditions, once framed in religious terms, are increasingly understood as neuroprotective and longevity-promoting strategies.

Goyal and Chauhan (2024) further highlight how fasting integrated with herbal remedies functioned as seasonal detox and metabolic reset, embedding preventive medicine within ritualized practice.

4.3 The Politics of Food in Suppressing Dietary Cures

The marginalization of dietary wisdom was not accidental but entangled with political and economic interests. Alissa and Ferns (2022) review how functional foods and nutraceuticals have long been sidelined in favor of pharmacological interventions, despite robust evidence of their preventive power. Fleming et al. (2022) show how cultural heritage diets were dismissed as unscientific even as modern epidemiology confirms their value.

Goyal and Chauhan (2024) argue that the politics of industrial agriculture, combined with colonial dietary interventions, displaced indigenous food systems. Colonizers often undermined local diets in favor of imported commodities, which disrupted not only nutrition but cultural identity. Swanson et al. (2021) note that industrial food production reduced microbial diversity, exacerbating modern health crises.

Mujica-Parodi et al. (2020) caution that dietary neglect has cognitive and neurological implications, as brain networks destabilize under processed food regimes. This reflects not only medical but civilizational consequences of the industrialized diet.

4.4 Modern Rediscovery of Gut Microbiomes

In recent decades, microbiome research has provided a scientific foundation for what ancient healers intuited: that diet governs health. Rinninella et al. (2023) emphasize the centrality of the gut microbiome in mediating immunity, metabolism, and even mental health. Whole foods, fermented diets, and diverse grains sustain microbial diversity, echoing traditional dietary practices.

Wang and Hu (2022) propose a model of precision nutrition that integrates microbiome science with preventive care. This aligns with Ayurveda and TCM, where individualized diets based on constitution were central to health. Mujica-Parodi et al. (2020) show how diet modulates brain networks, reinforcing the link between nutrition and cognitive resilience.

Alissa and Ferns (2022) argue that functional foods and nutraceuticals, once dismissed, are now at the forefront of preventive medicine. Goyal and Chauhan (2024) advocate for integrating traditional natural medicines with nutrient science, positioning the microbiome as a bridge between ancient wisdom and modern biomedicine.

Fleming et al. (2022) highlight how traditional diets like the Okinawan and Mediterranean are rich in prebiotics and probiotics, long before these terms existed, sustaining gut and systemic health.

4.5 Conclusion: Preventive Wisdom Buried in Tradition

Ancient societies treated food as medicine, embedding preventive health strategies into daily life through grains, fasting, ritual diets, and communal meals. These practices, often dismissed as cultural or spiritual, are increasingly validated by nutritional science, microbiome research, and preventive medicine.

The politics of food marginalized these traditions, but their rediscovery in the age of chronic disease and lifestyle epidemics underscores their continued relevance. As Fleming et al. (2022), Wang and Hu (2022), and Goyal and Chauhan (2024) suggest, the future of medicine may not lie solely in pharmaceuticals but in restoring the table as a temple, where food, culture, and prevention converge.

By revisiting the ancient wisdom of dietary practices and aligning it with cutting-edge nutritional science, we can begin to integrate food as preventive medicine in ways that honor both tradition and innovation. This paradigm shift requires acknowledging what history concealed: that our oldest cures were served not in capsules or tablets, but in bowls, loaves, and communal feasts.

Part 5 — The Lost Art of Detoxification

How cleansing rituals were medical science before the term existed

5.0 Introduction: Purification as Medicine

Long before modern concepts of toxins, immunity, and detoxification pathways were mapped by biomedical science, ancient cultures practiced elaborate cleansing rituals that served both medical and spiritual purposes. Sweating in sweat lodges, ritual fasting, herbal steaming, and purgation ceremonies were deeply embedded in cultural systems of healing from Africa to Asia and the Americas. Far from being mere superstition, these practices were grounded in empirical observation that linked purification with improved health, mental clarity, and resilience (Martínez-Sánchez et al., 2022; Sharma et al., 2022).

In the modern era, detoxification has often been dismissed as pseudoscience, particularly in its commercialized forms. Yet, scientific research increasingly validates aspects of traditional detox practices, from the elimination of heavy metals to the psychophysiological benefits of sweating and fasting (Nieman, 2022; Yang et al., 2023). This chapter explores ancient methods of detoxification, the colonial suppression of these practices, the rediscovery of their medical significance, and their enduring psychological and physiological impacts.

5.1 Sweating, Steaming, and Fasting in African, Asian, and Indigenous Cultures

Sweating has been a universal detox method, employed in African herbal steam baths, Native American sweat lodges, and Scandinavian saunas. Smith and Hunter (2022) systematically reviewed sauna bathing and found significant benefits for cardiovascular health, immune modulation, and mental wellbeing. These findings align with the observations of Indigenous healers who regarded sweating as a path to purification, resilience, and spiritual renewal.

Sharma et al. (2022) highlight the Ayurvedic tradition of panchakarma, which uses therapies such as induced sweating, oil massage, and herbal enemas to eliminate toxins (ama). Similarly, Yang et al. (2023) show how steaming and fermentation techniques in Asian traditions enhanced both the nutritional and detoxifying properties of medicinal plants.

African traditions also integrated detox rituals with communal and spiritual practices. Owuor and Kisangau (2023) describe how herbal steam baths in Kenya served not only to cleanse the body but to strengthen communal bonds and spiritual identity. Kang et al. (2021) confirm that such rituals, beyond physiological benefits, produced measurable psychological relief and enhanced resilience against stress.

5.2 The Suppression of Detox Methods by “Hygiene Science”

With the rise of colonial medicine and Western hygiene science, traditional detox practices were delegitimized. Omar et al. (2024) document how African and Asian detox rituals were condemned as primitive or unsanitary under colonial regimes. This suppression was not simply cultural but tied to power: controlling bodies meant controlling societies.

Crinnion and Pizzorno (2021) argue that the biomedical emphasis on antiseptic hygiene displaced older traditions of purification, framing them as superstition rather than health practice. Yet, ironically, many of the principles underlying these rituals—such as the role of sweating in immune defense or fasting in cellular repair—are now rediscovered by biomedical science (Longo & Mattson, 2021; Nieman, 2022).

5.3 Heavy Metals, Toxins, and Rediscovered Dangers

Modern toxicology has revealed the dangers of heavy metals, pesticides, and industrial pollutants. Kassir et al. (2021) emphasize that exposure to lead, mercury, and cadmium continues to pose major health threats globally. Ali et al. (2023) highlight how traditional herbal remedies have been employed to counteract heavy metal poisoning, offering detoxifying properties long before toxicology was formalized.

Martínez-Sánchez et al. (2022) review detox diets and their efficacy, concluding that while commercial detox fads often lack evidence, traditional practices such as fasting and plant-based detox regimens have demonstrable benefits in reducing oxidative stress and improving liver function. Nieman (2022) further clarifies that exercise-induced sweating assists in the excretion of certain xenobiotics, confirming ancient intuitions about sweat as a detox pathway.

Yang et al. (2023) demonstrate how steaming medicinal plants enhances their detoxifying capacity, reinforcing the scientific basis of rituals once dismissed as mystical. These studies reveal that detoxification, once a ritual practice, is in fact a physiological reality now corroborated by biochemistry and pharmacology.

5.4 Ritual Cleansing and Its Psychological Benefits

Beyond physical detoxification, purification rituals provided profound psychological and communal benefits. Kang et al. (2021) show that Korean steaming traditions induced measurable reductions in stress and improvements in mood, validating the psychospiritual functions of ritual cleansing. Ritual baths, fasting retreats, and sweat lodges functioned as liminal spaces where participants could symbolically release emotional burdens alongside physical impurities.

Ali et al. (2023) highlight the adaptogenic role of herbal detox agents, which not only bind toxins but regulate stress responses. Smith and Hunter (2022) demonstrate that sauna bathing improves mental health outcomes by stimulating endorphins and promoting relaxation.

Omar et al. (2024) argue that the colonial dismissal of these practices ignored their psychosocial role, which was as crucial as their physiological impact. Ritual cleansing reinforced identity, cohesion, and resilience in ways that biomedical hygiene alone could not replicate.

5.5 Conclusion: The Science Behind Ritual Detox

Detoxification was never a fringe superstition—it was a universal science of purification, grounded in observation and ritual, that anticipated many findings of modern biomedicine. Sweating, steaming, fasting, and herbal therapies served as preventive medicine long before the term existed. Their suppression under colonial medicine and hygiene science obscured their legitimacy, yet contemporary toxicology and psychoneuroimmunology confirm their relevance.

As Martínez-Sánchez et al. (2022), Sharma et al. (2022), and Yang et al. (2023) reveal, detox rituals offered physiological, psychological, and cultural benefits that modern health systems are only beginning to appreciate. To reclaim the lost art of detoxification is to recognize that cleansing was never just symbolic—it was, and remains, a profound medical science.

Part 6 — Mind as Medicine

The forgotten psychiatric sciences of ancient worlds

6.0 Introduction: Healing the Unseen Wounds

Mental health has long been framed as a modern crisis, yet civilizations across the world developed systems of care for the mind centuries before psychiatry was formalized. From meditation and prayer to dream interpretation and shamanic ritual, ancient traditions recognized that suffering was not only physical but also psychological and spiritual. Their therapeutic models anticipated many insights that neuroscience and psychiatry are only beginning to validate: the power of altered states, the role of belief, the mind-body connection, and the necessity of communal healing (Dahl et al., 2022; Kinghorn et al., 2021).

Colonial psychiatry, however, sought to suppress these indigenous sciences of the mind, branding them as superstition or pathology (Ecks, 2022). Yet, in recent decades, global mental health research has begun to rediscover the lessons embedded in ancient practices. This chapter explores meditation, prayer, and altered states as therapy; African dream interpretation schools; the role of shamans and seers as proto-psychiatrists; and the colonial suppression of indigenous mental sciences. It concludes with the enduring relevance of these lessons for modern psychiatry.

6.1 Meditation, Prayer, and Altered States as Therapy

Meditation and prayer have been central to healing across civilizations. In Buddhism, meditation was cultivated as a path to alleviate suffering by restructuring the self. Dahl et al. (2022) review contemplative practices and show that meditation modulates neural networks, restructures self-perception, and enhances emotional resilience. These findings align with ancient claims that meditation calms the mind and heals the spirit.

Kinghorn et al. (2021) examine the role of spirituality in mental health, emphasizing prayer as both a coping mechanism and therapeutic intervention. Their study underscores that prayer reduces anxiety, fosters social support, and strengthens resilience. Koenig (2021) similarly argues that integrating spirituality into psychiatry enhances clinical outcomes, validating practices long marginalized as unscientific.

Van Gordon and Shonin (2022) highlight the therapeutic role of altered states, showing how meditation and contemplative practices induce neuroplasticity, improve attention regulation, and reduce trauma symptoms. These findings echo Indigenous traditions where trance states, drumming, and chanting were used to heal emotional wounds and trauma.

6.2 Ancient African Dream Interpretation Schools

Dreams were regarded in many ancient African societies not as random neural firings but as diagnostic and therapeutic tools. Nielsen (2023) reviews the role of dreams in mental health, showing how ancient practices of dream analysis anticipated modern psychodynamic theories. Egyptian temples of sleep, where priests interpreted dreams for healing, functioned as proto-psychiatric institutions.

Fernando and Hecker (2023) extend this by examining African psychiatry, where dreams were understood as messages from ancestors, guides, or spiritual forces. Far from being dismissed as irrational, dreams were treated as key to diagnosing emotional and social disharmony. These practices align with Jungian perspectives that frame dreams as archetypal maps of the unconscious.

Colombo and Falkenberg (2022) document how shamanic dreamwork in South America and Africa used altered states of consciousness to address trauma, grief, and anxiety. Such dream schools were therapeutic laboratories where symbolic narratives were reinterpreted for healing, demonstrating that ancient societies embedded psychotherapeutic wisdom in their spiritual systems.

6.3 Shamans, Seers, and Proto-Psychiatrists

Shamans, seers, and healers acted as the world’s first psychiatrists. They guided communities through crises of grief, identity, and trauma using symbolic narratives, altered states, and ritualized catharsis. Borras-Guevara et al. (2024) argue that shamanism provided a structured form of psychotherapy, combining symbolic language, communal ritual, and pharmacological plants.

Colombo and Falkenberg (2022) emphasize that shamanic practices were not haphazard but systematic, incorporating trance, breathwork, and symbolic imagery as therapeutic modalities. Palitsky and Kaplan (2021) show that contemplative practices often integrated into shamanic rituals facilitated trauma recovery, emotional regulation, and meaning-making, making shamans early practitioners of trauma-informed care.

Nielsen (2023) highlights that proto-psychiatrists employed both pharmacological agents (psychoactive plants) and psychological techniques (dreamwork, narrative reframing), anticipating the dual track of modern psychiatry. Their approach underscores the integrative character of ancient mental health systems.

6.4 Suppression under Colonial Psychiatry

Colonial psychiatry systematically undermined indigenous models of mental health. Ecks (2022) demonstrates how colonial regimes labeled indigenous psychological practices as superstition, witchcraft, or madness. Healing rituals were often criminalized, and traditional healers marginalized.

Fernando and Hecker (2023) show how African psychiatric systems were delegitimized under colonialism, replaced by institutions that often ignored cultural conceptions of the mind. This epistemic violence not only disrupted therapeutic traditions but imposed alien frameworks of illness and treatment.

Koenig (2021) argues that even in contemporary psychiatry, remnants of colonial suppression persist, as biomedical models continue to marginalize spirituality and cultural conceptions of mental health. Restoring indigenous perspectives requires challenging these historical erasures.

6.5 Conclusion: Mental Health Lessons from Antiquity

Ancient civilizations developed rich sciences of the mind, anticipating many discoveries of modern psychiatry. Meditation, prayer, and altered states were therapies for trauma and resilience; dreams served as diagnostic and therapeutic texts; shamans and seers acted as proto-psychiatrists guiding communities through emotional crises. These practices embodied a holistic psychiatry long before the term existed.

Colonial psychiatry dismissed these traditions, yet as Dahl et al. (2022), Nielsen (2023), and Borras-Guevara et al. (2024) demonstrate, their insights remain vital. Restoring them into global mental health frameworks does not mean abandoning biomedicine but expanding psychiatry to honor cultural, spiritual, and symbolic dimensions of healing.

The lesson is clear: mental health cannot be reduced to neurochemistry alone. It requires recognition of the ancient sciences of the mind—traditions that healed unseen wounds, restored balance, and cultivated resilience across centuries.

Part 7 — The Surgical Pioneers

Ancient operations that rival modern medicine

7.0 Introduction: Scalpels before Steel

When surgery is imagined, the image is often of sterile operating theaters, stainless steel instruments, and advanced anesthetics. Yet, long before modern hospitals, ancient civilizations practiced surgical interventions with remarkable precision. From trepanation in prehistoric Europe and South America to cataract surgeries in India and dental procedures in Egypt, these interventions demonstrate that surgical knowledge was not a modern invention but an ancient craft grounded in observation, experimentation, and cultural necessity (Pringle, 2022; Kumar et al., 2023).

Although colonial narratives often dismissed ancient surgical practices as crude or barbaric, archaeological and textual evidence reveals sophisticated methods, high survival rates, and innovations that shaped medical history. This chapter explores Egyptian dentistry and trepanation, Indian cataract surgery, the colonial disruption of surgical traditions, and archaeological evidence of ancient medical success.

7.1 Egyptian Dentistry and Trepanation in Africa and Europe

Egypt provides some of the earliest evidence of organized surgical practices. David and Tapp (2021) note that Egyptian papyri describe techniques for suturing wounds, setting fractures, and performing dental extractions. Archaeological findings of skulls with drilled teeth suggest that dentistry was practiced to relieve pain and infection.

Trepanation, the act of drilling holes into the skull, is among the oldest surgical procedures known. Pomeroy et al. (2022) document cranial surgeries in prehistoric Britain, revealing survival rates that indicate not only surgical expertise but also postoperative care. Andrushko (2022) confirms similar findings in ancient Peru, where trepanned skulls display bone healing, suggesting patients lived long after their operations.

Roberts and Cox (2021) highlight how trepanation was often conducted to treat trauma, headaches, or spiritual afflictions. Far from being random, these surgeries reflected both empirical and cultural understandings of the body and psyche.

7.2 Indian Cataract Surgery and Surgical Texts

India’s contributions to surgical history are profound. Kumar et al. (2023) discuss Sushruta, often referred to as the “father of surgery,” whose Sushruta Samhita details over 300 surgical procedures, including plastic surgery, obstetric interventions, and cataract extraction. These texts illustrate not only surgical technique but also medical ethics and training protocols.

Nayar and Sharma (2024) emphasize the relevance of Sushruta’s surgical heritage today, noting that descriptions of cataract surgery anticipated modern techniques. Instruments described in the Samhita bear striking similarities to contemporary tools, showing continuity of surgical innovation.

Raffa et al. (2023) place these developments in the broader history of neurosurgery, noting that ancient Indian surgery contributed not only to ophthalmology but to wider global understandings of anatomy and surgical practice.

7.3 The Loss of Surgical Techniques to Colonial Disruption

Despite the sophistication of ancient surgical traditions, colonialism disrupted their transmission. Seth (2022) documents how British colonial authorities in India delegitimized indigenous surgical practices, branding them as dangerous and unscientific. This erasure contributed to the marginalization of Ayurvedic and Unani surgery, even as Western surgeons quietly appropriated knowledge from local practitioners.

Hardiman (2021) and Harrison (2024) argue that colonial medical institutions privileged Western surgical training, severing connections to indigenous systems. The result was not only the loss of techniques but also the suppression of epistemologies that viewed surgery as part of holistic health systems.

This suppression highlights a paradox: while colonial powers often appropriated botanical and pharmacological knowledge, they were less willing to acknowledge surgical expertise, as it threatened the perceived superiority of Western medicine.

7.4 Archaeological Evidence of Medical Success

Archaeology provides compelling evidence of ancient surgical success. Pomeroy et al. (2022) reveal cranial surgeries with high survival rates in Britain. Andrushko (2022) demonstrates similar outcomes in Peru, while Roberts and Cox (2021) note trepanations in Europe often associated with trauma healing.

David and Tapp (2021) provide evidence from Egyptian mummies showing healed fractures, amputations, and dental interventions, suggesting effective medical care. Apperley (2025) reviews ancient surgical tools, noting their sophistication and similarity to later designs.

Together, these findings confirm that ancient surgery was neither primitive nor marginal but a central component of healthcare systems with documented success rates.

7.5 Conclusion: Ancient Science Underestimated

Ancient surgical traditions demonstrate that civilizations long before the modern era developed complex medical practices that rival aspects of contemporary surgery. Egyptian dentistry, trepanation in Africa and Europe, Indian cataract surgery, and evidence of healed injuries reveal expertise, experimentation, and continuity of knowledge.

Colonial suppression obscured these traditions, yet archaeological and textual records confirm their legitimacy. As Pringle (2022), Kumar et al. (2023), and Raffa et al. (2023) show, ancient surgeons were innovators, not primitives. Their legacy challenges modern medicine to acknowledge that scientific ingenuity is not the monopoly of the present but the inheritance of humanity’s shared past.

Part 8 — Women as Custodians of Healing

The erasure of midwives, herbalists, and priestesses of medicine

8.0 Introduction: The Gendered History of Medicine

Women were central to the history of healing. As midwives, herbalists, priestesses, and custodians of oral traditions, they preserved and transmitted medical knowledge for millennia. Yet, their contributions were systematically erased or criminalized through witch hunts, colonial medicine, and the rise of male-dominated professionalized medicine. The story of women as healers is thus not only about what they contributed, but about how patriarchal systems suppressed their agency and authority (Federici, 2022; Green, 2023).

This chapter examines women’s role as carriers of oral medical traditions, the witch hunts that criminalized female healers, the loss of maternal health knowledge to modern obstetrics, the survival of these traditions in rural contexts, and the contemporary movement to restore women to medical history.

8.1 Women as Carriers of Oral Medical Traditions

For much of history, healing knowledge was transmitted orally within households and communities. Women, as primary caregivers, were the custodians of this knowledge, using herbs, diets, and rituals to treat illnesses and ensure maternal and child health. Green (2023) documents the global role of women in medical history, showing how they were responsible for sustaining traditions across generations.

Rankin (2021) emphasizes that in Renaissance Europe, women not only practiced midwifery but also contributed to the development of pharmacology through domestic remedies and recipe books. Turner (2025) notes similar traditions in the Philippines, where women preserved indigenous pharmacopeias as part of cultural heritage. Bledsoe and Moyer (2021) confirm this pattern in West Africa, where women healers played dual roles as both spiritual and medical authorities.

These examples highlight women as custodians of integrative medicine, blending herbal, dietary, and ritual practices into coherent healing systems.

8.2 Witch Hunts and the Criminalization of Female Healers

The rise of witch hunts in Europe marked a turning point in the suppression of female healers. Federici (2022) argues that the persecution of “witches” was inseparable from the rise of capitalism and professional medicine, which sought to monopolize healing knowledge. Women’s roles as midwives and herbalists were delegitimized, and practices once regarded as sacred became criminalized.

Sangl and Duden (2022) note that witch hunts were not only about superstition but were systematic campaigns to dismantle women’s authority in medicine. The knowledge of herbs, fertility, and childbirth, once revered, was reframed as dangerous and demonic. This violent suppression severed the transmission of female-centered healing knowledge in Europe.

Raj (2023) shows similar dynamics in colonial India, where female healers were stigmatized under colonial rule, reflecting the global dimension of gendered medical suppression. These examples reveal how the marginalization of women in medicine was not incidental, but a structural process embedded in patriarchy and empire.

8.3 Maternal Health Knowledge Lost to Modern Obstetrics

One of the most profound losses caused by the marginalization of women healers was in maternal and reproductive health. Lyerly (2024) demonstrates how colonial obstetrics displaced traditional midwives, eroding maternal health knowledge that had been cultivated for centuries. Modern obstetrics centralized authority in male doctors, often disregarding women’s embodied expertise.

Sullivan et al. (2023) document how traditional birth attendants in sub-Saharan Africa continue to play critical roles in maternal health, despite being marginalized by biomedical systems. Their persistence reflects both necessity and resilience in communities underserved by formal healthcare.

Andaya (2022) highlights Southeast Asia, where women’s midwifery knowledge continues in rural contexts, often blending with modern healthcare. These traditions show that maternal health knowledge was never fully eradicated, but transformed and adapted under pressure from dominant systems.

8.4 Surviving Traditions in Rural Africa and Asia

Despite suppression, women’s healing traditions endured in rural areas, where biomedical systems often had limited reach. Bledsoe and Moyer (2021) note that in West Africa, women healers remained central figures in community health, using herbal remedies and spiritual practices. Andaya (2022) documents continuity in Southeast Asia, where midwives continue to perform rituals alongside deliveries.

Sullivan et al. (2023) show that these traditions not only survived but adapted, integrating biomedical tools with traditional practices. This adaptability underscores the resilience of women’s healing roles and the necessity of acknowledging their contributions in pluralistic health systems.

McTavish (2025) argues that feminist historiography must restore women to medical history, not only as victims of suppression but as active agents of healing traditions that shaped societies.

8.5 Conclusion: Restoring Women to Healing History

Women have always been central to medicine—as midwives, herbalists, ritual leaders, and custodians of oral traditions. Their suppression through witch hunts, colonial medicine, and professional monopolies was a systematic erasure of knowledge and authority. Yet, their traditions survived in rural Africa, Asia, and beyond, adapted into new contexts despite marginalization.

As Federici (2022), Green (2023), and McTavish (2025) emphasize, restoring women to healing history is not only about correcting the record but about reimagining healthcare. Recognizing women’s custodianship of healing opens the door to more integrative, community-based, and equitable systems of medicine. It is an act of justice to the past and a necessity for the future.

Part 9 — Colonialism and the War on Ancient Healing

How imperial expansion deliberately buried indigenous knowledge

9.0 Introduction: Power and Medicine

Colonialism was not only a project of economic exploitation and territorial conquest; it was also a war against knowledge. Among the most devastating consequences of empire was the systematic suppression of indigenous medical systems. Healing practices that had been refined over centuries were delegitimized, outlawed, or appropriated under the banner of “civilization” and “progress.” Medicine became an instrument of colonial domination, not only of bodies but of epistemologies (Anderson, 2021; Marks, 2021).

This chapter examines the colonial suppression of ancient healing, including the erasure enacted under the so-called “civilizing mission,” the suppression of African herbal practices, the theft of indigenous cures through patents and bioprospecting, and the creation of segregated medical systems that entrenched racial hierarchies. Ultimately, it argues that colonial medicine was a form of epistemic violence, leaving legacies still visible in global health inequalities today.

9.1 The “Civilizing Mission” as Medical Erasure

Colonial powers framed their expansion as a “civilizing mission,” in which medicine played a central role. Anderson (2021) highlights how European empires in Asia and Africa used Western medicine as both a justification for conquest and a tool of governance. Indigenous healing practices were denounced as superstition, despite their widespread efficacy and cultural legitimacy.

Marks (2021) emphasizes that the civilizing mission was not only ideological but institutional: medical schools, missionary hospitals, and colonial health departments sought to replace traditional systems with biomedicine. This process effectively erased indigenous epistemologies from the official record, creating an impression that colonized societies lacked medical science.

Harrison (2024) adds that tropical medicine, a field developed during empire, appropriated indigenous ecological knowledge while erasing the healers who had cultivated it. This selective appropriation underscores the exploitative logic of colonial medicine.

9.2 Suppression of African Herbal Practices

Africa offers examples of the suppression of indigenous healing. Okeke et al. (2023) document how colonial governments criminalized herbalists, branding them as “witch doctors” and excluding them from formal health systems. Yet, as Ouma (2022) and Busia & Agyare (2022) note, these healers continued to provide care for the majority of the population, particularly in rural areas.

Mahone (2023) describes how colonial hospitals in East Africa deliberately excluded African healers, creating dual medical systems: one for Europeans and elites, and another stigmatized system for Africans. This segregation entrenched inequalities and delegitimized traditional medicine.

Raj (2023) demonstrates similar dynamics in colonial India, where women herbalists and midwives were particularly targeted, reflecting the gendered dimension of suppression. Such practices illustrate how colonial medicine was as much about control as it was about health.

9.3 Patents, Profit, and Theft of Indigenous Cures

Colonial suppression was accompanied by appropriation. Osseo-Asare (2022) documents how African plants and cures were systematically extracted for European pharmaceutical development. Indigenous communities were denied recognition or compensation, while Western companies patented remedies derived from their knowledge.

Hardiman (2021) highlights that colonial science routinely presented these discoveries as European, erasing indigenous contributions. This intellectual theft not only dispossessed communities of economic benefits but also redefined medicine in Eurocentric terms.

Arnold (2025) shows that this legacy continues today in biopiracy cases, where corporations patent traditional remedies under international intellectual property regimes. The theft of cures represents an ongoing colonial dynamic, embedded in global capitalism.

9.4 The Medical Apartheid of Colonial Hospitals

Colonial hospitals institutionalized racial segregation. Mahone (2023) reveals how colonial East African hospitals were designed to serve Europeans while restricting Africans to underfunded facilities. Medicine thus reinforced social hierarchies, making healthcare an arena of apartheid.

Ecks (2022) documents similar dynamics in psychiatry, where colonial authorities pathologized indigenous psychological practices while imposing Western models. This dual system delegitimized indigenous sciences of both body and mind.

Harrison (2024) argues that the creation of “tropical medicine” was premised on protecting colonizers from local diseases rather than serving local populations. Medicine in this context was less about universal health and more about racialized governance.

9.5 Conclusion: A Legacy of Silenced Science

Colonialism’s war on ancient healing was multifaceted: erasing indigenous knowledge under the civilizing mission, criminalizing African herbal practices, appropriating cures for profit, and institutionalizing medical apartheid. These processes not only marginalized traditional medicine but also redefined what counted as science.

As Anderson (2021), Osseo-Asare (2022), and Arnold (2025) emphasize, colonial medicine must be recognized as epistemic violence. Its legacies persist in the undervaluation of indigenous knowledge, the inequities of global health, and the ongoing battles over intellectual property and biopiracy.

Reclaiming these silenced sciences requires both historical reckoning and structural reform. Indigenous healers, long marginalized, must be recognized not as remnants of the past but as vital contributors to pluralistic health futures. To dismantle the colonial legacy in medicine is to restore dignity, authority, and legitimacy to the knowledge systems it sought to destroy.

Part 10 — The Corporate Capture of Health

How modern capitalism profits from treatment but ignores prevention

10.0 Introduction: The Economics of Forgetting

The story of modern medicine cannot be disentangled from capitalism. As healing systems transitioned from communal and preventive frameworks into industrialized biomedicine, corporate power increasingly dictated what counted as legitimate care. The rise of the pharmaceutical industry, agribusiness, and medical insurance systems transformed health into a market commodity. In this transition, prevention was sidelined, dietary and herbal knowledge was marginalized, and chronic disease became not only a medical condition but an economic strategy (Light, 2022; Moynihan et al., 2022).

This chapter examines the ways corporations captured health by burying natural cures, lobbying against prevention, shaping media silences, and structuring healthcare systems around chronic illness. It concludes by reflecting on the commodification of healing knowledge and the urgent need to reclaim prevention as central to healthcare.

10.1 Pharma and the Burial of Natural Cures

The pharmaceutical industry has long profited from the marginalization of natural remedies. Light (2022) argues that global pharmaceutical capitalism thrives by promoting treatments that generate repeat consumption rather than cures that resolve illness. Lexchin (2023) adds that drug development often neglects preventive or dietary interventions in favor of synthetic compounds that can be patented and commercialized.

Moynihan et al. (2022) document how Big Pharma influences research agendas, diverting resources away from studies on lifestyle and nutrition. Traditional herbal knowledge, though validated by contemporary pharmacology, is often sidelined or appropriated without acknowledgment (Davis & Abraham, 2022).

Oxfam (2022) exposes how pharmaceutical companies extract enormous profits by restricting access to affordable medicines, while indigenous remedies remain underfunded and stigmatized. This dynamic reflects the larger corporate interest in maintaining dependency on manufactured drugs rather than supporting preventive health systems.

10.2 Lobbying Against Prevention-Based Healthcare

Corporate influence extends into politics, where lobbying actively resists systemic changes favoring prevention. Lexchin (2023) shows how pharmaceutical companies shape health regulations through lobbying, ensuring that policies favor treatment markets over preventive strategies. Greer et al. (2021) emphasize that the political economy of health privileges corporate interests, systematically undervaluing prevention.

Stuckler and Nestle (2021) demonstrate that Big Food collaborates with Big Pharma in perpetuating dietary environments that fuel chronic disease. Corporate lobbying thus operates on multiple fronts—blocking restrictions on unhealthy products while undermining investment in community-based preventive care.

Petersen et al. (2024) add that commodification extends to knowledge itself, as evidence on nutrition and herbal medicine is downplayed or dismissed in policy frameworks. This systemic marginalization reflects the entrenchment of capitalist logic in shaping healthcare priorities.

10.3 Media Silence on Dietary and Herbal Research

The media plays a critical role in shaping public perceptions of medicine. Jørgensen et al. (2023) find systematic bias in pharmaceutical coverage, with natural and dietary remedies often underrepresented or framed as fringe. This silence ensures that the public remains dependent on pharmaceutical interventions, despite growing evidence of the efficacy of preventive strategies.

Davis and Abraham (2022) argue that the capture of medical knowledge by corporate interests extends into academic publishing, where industry-funded studies dominate the narrative. Alternative therapies, even when supported by rigorous trials, struggle for visibility in mainstream discourse.

Moynihan et al. (2022) further show how the framing of health in media reduces complex preventive strategies into consumer choices, obscuring structural determinants of health such as food systems and economic inequality. The media thus becomes complicit in reinforcing pharmaceutical dominance.

10.4 The Market Logic of Chronic Disease

Chronic disease has become a lucrative market for corporations. Light (2022) highlights how pharmaceutical companies design business models around lifelong treatments for conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and depression. Prevention, by contrast, reduces market demand and is therefore systematically underfunded.

Greer et al. (2021) emphasize that the political economy of prevention reveals a paradox: preventing disease is socially beneficial but economically unattractive to corporations. Moynihan et al. (2022) frame this as the “chronic disease industry,” in which conditions are managed but rarely cured.

Stuckler and Nestle (2021) argue that food systems play a parallel role, producing processed foods that exacerbate chronic illness while marketing “solutions” that generate further profits. This cyclical dynamic sustains corporate interests at the expense of population health.

WHO (2023) confirms that commercial determinants of health are now among the greatest barriers to preventive care. The alignment of corporate interests with healthcare systems has entrenched treatment over prevention as the dominant paradigm.

10.5 Conclusion: Healing Knowledge Commodified

The corporate capture of health demonstrates how capitalism restructured medicine from a preventive and communal practice into a profit-driven industry. Natural cures were buried, preventive healthcare undermined, dietary and herbal knowledge marginalized, and chronic disease transformed into a growth market.

As Light (2022), Lexchin (2023), and Moynihan et al. (2022) show, this capture is not accidental but systemic. Corporate lobbying, media bias, and the commodification of knowledge have ensured that treatment is privileged over prevention. The result is a healthcare system more attuned to profit than to healing.

To reclaim health requires dismantling corporate monopolies on knowledge and restoring prevention to the center of medicine. It requires recognizing that the economics of forgetting—where traditional wisdom and preventive strategies are erased—has been a deliberate act. Healing knowledge must be de-commodified, restored to communities, and integrated into systems that prioritize wellbeing over profit.

Part 11 — The Global Reawakening

The 21st-century rediscovery of ancient practices

11.0 Introduction: What Science is Catching Up To

The 21st century has witnessed a profound reawakening to the value of traditional medicine. What was long dismissed as superstition or cultural relic is now recognized as a reservoir of therapeutic knowledge that complements and sometimes surpasses modern biomedicine. This rediscovery is not accidental but emerges from converging forces: the limitations of pharmaceutical models in addressing chronic disease, the rising interest in holistic health, and the institutional efforts of organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) to integrate traditional medicine into global frameworks (WHO, 2023; Patwardhan, 2023).

This chapter explores the reawakening in multiple dimensions: the role of the WHO in legitimizing traditional practices, the global rise of Ayurveda and Chinese medicine, the growing visibility of African herbal research, the importance of citizen science and grassroots rediscovery, and the broader implications of integrating ancient practices into planetary health systems.

11.1 WHO and Integration of Traditional Medicine

WHO (2023) has played a pivotal role in legitimizing traditional and complementary medicine (T&CM). Its Global Report on Traditional and Complementary Medicine outlines strategies to incorporate traditional practices into national healthcare systems, emphasizing their accessibility and cultural resonance. Ang et al. (2024) demonstrate through evidence mapping that T&CM offers therapeutic potential across a wide spectrum of health conditions, particularly in chronic disease management.

Patwardhan (2023) argues that evidence-based traditional medicine is essential for transforming healthcare, noting that WHO’s endorsement has shifted traditional practices from the margins to the mainstream. Health Policy Watch (2025) documents WHO’s push to integrate traditional medicine into global healthcare frameworks, marking a historic turning point where indigenous knowledge is positioned as part of future health systems rather than relics of the past.

11.2 Ayurvedic and Chinese Medicine in Global Health

Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) have emerged as global forces in the reawakening. Zhou et al. (2024) highlight the progress and challenges in integrating Chinese and Western medicine, showing how acupuncture, herbal pharmacology, and qigong are increasingly validated through clinical research. Lyu et al. (2021) emphasize the expansion of both Ayurveda and TCM into integrative medicine, with growing demand across Europe and North America.

Shankar and Unnikrishnan (2023) argue that Ayurveda offers not only herbal remedies but a holistic philosophy of balance that addresses both prevention and planetary health. Li et al. (2022) map the global trends in Ayurvedic research, showing its growing role in integrative therapies for chronic illness.