By Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

Investigative Journalist | Public Intellectual | Global Governance Analyst | Health & Social Care Expert

Editorial Statement

Where journalism ends, the architecture of monetization begins.

The digital news economy is not simply a platform for information; it is a sophisticated ecosystem where power, psychology, and profit intersect. The perception of free journalism—headlines available at no cost, articles unlocked with a click—is an illusion that masks an intricate financial engine. What sustains digital publishing is not merely the craft of storytelling, but the ability to transform attention into a commodity, to convert engagement into currency, and to monetize human behavior at scale.

In this architecture, the audience is not the consumer but the product. Each scroll, share, and outrage-laden reaction is measured, priced, and sold in markets largely invisible to the public eye. Algorithms, designed by opaque corporate entities, dictate which stories surface and which vanish, privileging the provocative and the emotive over the balanced or nuanced. Newsrooms once driven by editorial judgment now coexist uneasily with commercial imperatives that reward virality and punish subtlety.

This series of investigations seeks to expose and decode the hidden circuits of profit that underpin the global news economy. It examines the silent machinery of programmatic advertising, the blurred borders between editorial and commerce, the psychology of outrage as monetization, and the ascent of newsletters as digital empires in their own right. It demonstrates that financial sustainability in journalism has less to do with subscription models or banner ads than with mastering the logic of platforms, leveraging data flows, and exploiting the economics of attention.

Yet, this exposé is not merely diagnostic; it is revelatory. It reveals opportunities for small publishers as much as it critiques the concentration of power in global platforms. It challenges journalists, entrepreneurs, and policymakers alike to recognize that news is no longer simply a democratic institution, but also a commercial infrastructure whose future rests on innovation, strategy, and the willingness to confront uncomfortable truths.

What emerges is a stark conclusion: journalism wears the mask of service, but behind it lies a machine engineered for profit. Understanding this code is no longer optional—it is essential.

— The Editorial Board

People & Polity Inc., New York

Executive Summary

From Eyeballs to Empires: Strategic Pathways to Monetizing Digital News

This report investigates the evolving dynamics of digital journalism, exposing the mechanisms that underpin online media profitability and the structural shifts transforming the global information economy. It reveals that the perception of “free news” is a myth: in reality, digital publishing is built on a complex architecture where human attention, data flows, and algorithmic systems converge to generate profit.

The analysis highlights the paradox at the heart of modern journalism: while editorial credibility remains a core value, sustainability increasingly depends on diversified revenue models—programmatic advertising, affiliate commerce, sponsored content, paywalls, and newsletters. Each of these models leverages audience behavior in distinct ways, transforming clicks, subscriptions, and emotional engagement into measurable financial outcomes. The study underscores that programmatic advertising has democratized access, enabling even small regional publishers to monetize global audiences, albeit at lower margins. At the same time, premium models such as memberships and exclusive newsletters demonstrate that loyalty and trust can be monetized at far higher rates than display ads.

Another critical insight is the central role of platforms and algorithms. Visibility and reach are no longer neutral but governed by opaque rules embedded in search engines and social platforms. This algorithmic mediation not only rewards outrage-driven content but also shapes the very contours of public debate. The commodification of anger, fear, and curiosity illustrates how digital publishing has fused economics with psychology, creating a marketplace of emotions as much as one of information.

Finally, the report projects forward, arguing that the future of digital journalism lies in strategic innovation—AI-driven personalization, blockchain-based paywalls, and novel monetization experiments that transform news into a hybrid of information service and commercial enterprise. For both established and emerging publishers, the key challenge is not merely survival but mastering the hidden code: converting fragmented attention into sustainable streams of revenue while maintaining editorial legitimacy.

In summary, the study concludes that digital news is no longer simply about journalism; it is about decoding and exploiting the hidden circuits of profit embedded within the architecture of the modern attention economy.

Part 1—Introduction: Cracking the Forbidden Code

What looks like journalism is only the mask—behind it lies the code that turns your clicks into currency.

1.1 Open with the Illusion of “Free News” Online

Today’s readers live in an age where information feels limitless and free. Each morning, millions reach for their phones and dive into endless streams of headlines: political drama, sporting triumphs, scandals, natural disasters, celebrity gossip, and economic predictions. It feels effortless, almost like a natural right—knowledge pouring in without a single bill attached.

Gone are the days of the newspaper delivery boy knocking at the door, asking for a subscription fee. No one drops a coin into a kiosk before turning the pages. There’s no check mailed to a TV broadcaster for access to the nightly news. Now, everything is instant and seemingly free, just one click away.

This perception of “free news” has become so ingrained that most people rarely question it. Journalism presents itself as a public service, sustained by some invisible force. The story seems simple: writers write, editors polish, publishers distribute, and society benefits. We’re led to believe generosity is the business model.

But illusions are carefully built. The magician waves one hand to distract the eye while the real trick happens in the other. The same principle applies to online journalism. What looks free on the surface is actually a calculated transaction. You don’t hand over money at the door—you pay with something even more valuable behind it: your attention, your data, your time, and increasingly, your emotions.

1.2 State the Exposé Claim: News Sites Don’t Survive on Journalism, but on Hidden Profit Codes

Here’s the unsettling truth: news organizations don’t survive because of journalism. Investigative reporting, polished storytelling, and the noble mission of informing society matter—but they aren’t what keep the operation alive. They’re the mask.

The real fuel comes from a hidden architecture of finance—profit codes. These codes dictate how stories are framed, when they’re published, how they’re distributed, and sometimes whether they get published at all.

In this world:

- Journalism is the bait.

- Attention is the currency.

- Data tracking is the infrastructure.

- Ads, affiliates, and memberships are the engines.

Most readers think journalism is the product. In reality, readers themselves are the product. Every headline you click, every scroll, every pause before a video ad isn’t just casual engagement—it’s an entry in a financial ledger.

This exposé makes a bold claim: modern journalism is less about truth and more about managing this hidden economic code. Once you understand it, you’ll never see an article as “just information” again—you’ll see a storefront in a vast attention marketplace.

1.3 Promise Readers a Leak of the Secret System Behind Online News Money

This isn’t guesswork or cynical ranting. It’s an unmasking. In this series, we’ll crack the forbidden code—the unspoken business model sustaining digital news today.

Here’s what’s coming:

- Why “free content” is a myth and how every click has an unseen cost.

- How advertisers, affiliate partners, and sponsors quietly shape the news.

- Why platforms like Google, Facebook, and TikTok act as unseen gatekeepers.

- How outrage and fear are engineered because they generate the most profit.

- Why newsletters, personalization through AI, and even crypto paywalls are becoming the next big monetization tools.

By the end, you won’t just know how journalism survives—you’ll see the code. And once you see it, the illusion falls apart.

1.4 Case Study: BuzzFeed, Outrage Headlines, and the Profit Illusion

Take BuzzFeed News, once hailed as the shining future of online journalism. Its site was a mix of serious reporting, listicles, and viral quizzes. To casual readers, it looked like free entertainment and information. But behind the curtain, its engine ran on one thing: clicks and shares.

BuzzFeed didn’t thrive by selling newspapers; it grew by mastering Facebook’s algorithm. Its team learned to craft headlines that provoked emotions—humor, shock, and outrage. Every share on social media wasn’t just a spread of information; it was a data point about who shared, when, and why. That data was then sold into advertising markets.

The public saw “free news.” Investors saw a highly efficient machine for harvesting attention. But when Facebook’s algorithm shifted, BuzzFeed News faltered. The collapse didn’t happen because journalism failed, but because the profit code broke.

This case reveals a hard truth: survival in digital journalism has less to do with truth and more to do with playing by the hidden rules of profit.

1.5 Why Readers Must See the Code

So why tear the curtain back? Why not let the system run in the background while readers enjoy their free stories? The answer is simple: power and accountability.

First, power. If readers remain blind to the code, they unknowingly play the role of passive commodities. They think they’re consuming content, but in reality, they’re the ones being consumed.

Second, accountability. Journalism prides itself on holding governments and corporations accountable. But what happens when journalism itself is bound by financial strings? If the industry can’t be transparent about its dependence on hidden codes, then the public must learn to recognize them.

Only by seeing the code can readers demand honesty, fairness, and reform.

1.6 A Warning for What Lies Ahead

This is just the prologue. The code only grows darker from here. Next, we’ll dismantle the illusion of “free journalism” and show why nothing you consume online is ever truly free. We’ll reveal why your data is worth more than any subscription fee and how your attention has been turned into a trillion-dollar asset.

Keep this warning close: every click you make is currency. You may not notice the exchange, but the system records it. Every article opened, every angry share, every video replayed—these are coins you never see, but which someone else is cashing in.

The code isn’t just hidden—it’s forbidden. Because once you learn to see it, the industry loses its most effective tool: your ignorance.

Part 2—The Illusion of Free Journalism

Every free headline comes with a hidden invoice—you just don’t see who’s cashing it in.

2.1 Why “Free Content” is Never Truly Free

One of the most enduring myths of the digital age is that online journalism is free. From the perspective of the casual reader, this appears self-evident: news sites rarely charge for entry, and thousands of stories can be accessed with a single click. Yet this apparent generosity is misleading. Journalism, like any enterprise, requires revenue to survive. Reporters must be paid, servers must be maintained, and platforms must invest in constant technological upgrades.

The fact that readers rarely hand over cash does not mean journalism is free—it means the cost is hidden. Instead of money, the transaction is attention, data, and behavior. Each time a visitor loads a webpage, a complex behind-the-scenes market springs into action. Advertising networks bid in real time for the chance to display targeted messages. Cookies track user activity across platforms. Attention, measured in clicks, scrolls, and engagement time, is converted into financial value.

As the Reuters Institute’s Digital News Report 2025 shows, more than 80% of global online audiences still access news without paying, relying on free content supported primarily by advertising and data-driven monetization (Newman, 2025). In other words, journalism may look free, but readers pay in other currencies. The myth survives only because the transaction is invisible.

2.2 Readers as the Product, Not the Customers

The second layer of the illusion is more unsettling: readers are not the customers of digital journalism—they are the product being sold. The real customers are advertisers, sponsors, and third-party networks willing to pay for access to human attention.

This inversion explains much of the online news economy. Instead of serving audiences as citizens, many outlets serve them as commodities. Articles are optimized not only for accuracy but for virality. Headlines are sharpened to trigger emotions—anger, fear, joy, or surprise—because emotional engagement keeps readers on the page longer, increasing the value of advertising slots.

The World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers highlights this in its World Press Trends Outlook 2025, noting that even as subscriptions grow slowly, digital advertising and “other revenue streams” continue to be the dominant stabilizers for publishers worldwide (WAN-IFRA, 2025). In short, most outlets cannot survive without selling access to audiences in one form or another.

When readers believe they are customers, they imagine they have power. Customers can demand better service, more transparency, or improved quality. But when readers are actually the product, their power is minimal. Products do not negotiate. They are packaged, priced, and traded. This explains why outrage-driven headlines persist despite audience complaints: the incentives are not aligned with serving the reader but with maximizing the product’s market value.

2.3 The Hidden Transaction: Attention Exchanged for Money

The final element of the illusion is the hidden transaction itself. Each act of consuming news—clicking a headline, scrolling through a story, watching a video—is a micro-transaction in a vast digital economy. Unlike traditional transactions, however, the user is rarely aware of the exchange.

Programmatic advertising has made this market hyper-efficient. Within milliseconds of a reader opening a page, automated systems auction their attention to the highest bidder. The advertiser who wins the bid places an ad, often tailored using detailed behavioral data. The reader may see only a banner or a video, but behind it lies a cascade of invisible deals, financial flows, and data transfers.

This dynamic has redefined journalism itself. Outlets no longer compete solely on credibility or public service—they compete on their ability to harvest and monetize attention more effectively than their rivals. As Indiegraf’s (2024) study of subscription and revenue models explains, the reliance on “free” access means many outlets double down on engagement metrics, even when paywalls are introduced, because attention remains the primary driver of long-term sustainability.

The illusion of free news masks this economy. Readers assume they are simply being informed. In reality, they are engaged in constant, unacknowledged transactions in which their time, behavior, and emotions are the currency.

2.4 Academic Implications of the Illusion

From an academic perspective, the illusion of free journalism raises questions about media ethics, democratic accountability, and the sustainability of public-interest reporting. If journalism is financed primarily through hidden profit codes, then editorial independence becomes vulnerable to the pressures of market logic. Stories that drive outrage or viral clicks are prioritized, while slow, investigative work struggles to compete.

Moreover, the illusion complicates the relationship between media and democracy. Journalism has long been described as the “fourth estate,” a watchdog for the public. Yet when audiences are treated as commodities rather than citizens, the democratic mission of the press is undermined. News becomes not a civic good but a commercialized spectacle.

This dual identity—public service on the surface, profit machine underneath—creates structural tensions that will shape the future of journalism. As Newman (2025) notes, trust in journalism continues to decline globally, precisely because audiences sense that the news they consume is being filtered and shaped by forces beyond editorial judgment.

2.5 The Psychological Power of “Free”

Psychology explains why the illusion is so effective. The human brain is drawn to “free” offers, even when hidden costs exist. Free access lowers resistance, widens audiences, and normalizes constant consumption. Once hooked, readers are far more likely to share, comment, or engage, each action feeding the monetization cycle.

Publishers understand this deeply. The promise of “free” builds massive audiences, which can later be nudged toward premium subscriptions, exclusive memberships, or branded merchandise. The free tier, then, is not generosity—it is a funnel, a mechanism to harvest attention and guide readers into deeper economic relationships with the brand.

2.6 Conclusion: Cracks in the Illusion

The illusion of free journalism is powerful because it flatters both readers and publishers. Readers feel they are receiving a gift. Publishers maintain the appearance of public service. Yet beneath this mask lies a system of hidden transactions in which attention, not money, is the core currency.

This has profound implications for the future. As WAN-IFRA (2025) observes, publishers are diversifying revenue streams—subscriptions, donations, memberships—but advertising and data remain dominant. Until this balance shifts, the illusion will persist.

The challenge for journalism is whether it can reconcile its democratic mission with its economic reality. If audiences continue to be treated as commodities, trust will erode further. If, however, publishers can find ways to make transactions transparent—acknowledging the true cost of “free” content—then perhaps journalism can rebuild its legitimacy in the digital age.

Part 3—The Secret Formula of Digital Profits

Behind every headline lies an equation: traffic, data, and profit—the secret formula that powers the digital news economy.

3.1 Traffic—The Currency of Eyeballs

The digital publishing economy is built on a deceptively simple principle: attention equals value. Every visitor who lands on a news website, scrolls through an article, or watches a video becomes part of a global marketplace where human attention is bought, sold, and repackaged. Unlike the traditional print model, where circulation figures determined advertising value, the digital era operates on real-time, granular metrics. Clicks, impressions, page dwell time, bounce rates, and shares are the new currencies.

According to the Internet Advertising Revenue Report (Interactive Advertising Bureau and PwC, 2025), U.S. internet advertising revenues reached over $225 billion in 2024, representing year-on-year growth of nearly 10%. Much of this growth was directly tied to the ability of publishers to capture, sustain, and monetize traffic flows. Every spike in site visits translates into higher bidding competition among advertisers for screen space, increasing the publisher’s revenue.

Traffic, however, is not neutral. Newsrooms strategically design their content pipelines around traffic maximization. Headlines are tested and optimized, content is scheduled for peak user activity, and breaking news alerts are carefully timed to coincide with periods of highest online engagement. Platforms like Chartbeat and Google Analytics are no longer mere support tools—they have become integral to editorial decision-making.

The Guardian, for example, reported in 2023 that articles pushed during the early morning commute and evening hours consistently outperform midday stories in terms of page dwell time and shares. Smaller publishers, including niche African digital outlets, often focus on viral topics or social media-driven headlines to cut through algorithmic noise. In both cases, the goal is clear: capture as many eyeballs as possible, for as long as possible.

Traffic is the foundation of the formula. But traffic alone is not enough. To transform raw attention into sustainable profit, publishers must convert this flow into something more measurable, predictable, and commodifiable: data.

3.2 Data—The Invisible Goldmine

If traffic is the surface-level currency, data is the subterranean goldmine that powers the industry. Every scroll, click, share, and subscription produces data points. These data points—when aggregated and analyzed—allow publishers to build detailed profiles of their audiences.

This profiling is what makes digital advertising so lucrative. Advertisers no longer need to cast wide nets; they can target precise demographics, interests, and even psychological traits. For example, a reader who frequently clicks on articles about electric cars might be shown targeted ads from Tesla, Ford, or charging infrastructure providers. Similarly, someone engaging with health-related articles could be placed in segments attractive to pharmaceutical or wellness brands.

The State of Publisher Revenue Streams in 2025 (Gradient Group, 2025) emphasizes that first-party data collection has become a critical strategy for publishers in an era of increasing privacy regulation and the phasing out of third-party cookies. This trend has forced outlets to invest heavily in data infrastructure—encouraging newsletter sign-ups, paywall registrations, and membership schemes not only for revenue but also to capture valuable first-party audience data.

For example, The New York Times has openly stated that one of the most significant benefits of its subscription model is not just recurring revenue but the treasure trove of reader data it provides. This data enables hyper-personalization of content and more profitable advertising placements. African publishers like Africa Digital News have also begun experimenting with lightweight registration systems, giving readers free access to stories but requiring an email or phone number in return.

In effect, data turns the unpredictable ebb and flow of traffic into a structured resource. While traffic measures presence, data measures identity and behavior. And it is this data that fuels the final step of the formula: profit.

3.3 Profit—Monetization Mechanisms in Action

The final element of the formula transforms traffic and data into profit. Digital publishers rely on a range of monetization strategies, often layering them to maximize revenue resilience.

The Top 5 Proven Revenue Models for Digital Publishers report by Broadstreet Ads (2024) outlines five dominant models: programmatic advertising, direct-sold advertising, sponsored content, affiliate marketing, and subscription/membership. While different publishers emphasize different mixes, most major outlets use some combination of these streams.

Programmatic Advertising

This remains the dominant revenue driver for most digital publishers. Automated auctions sell ad inventory in milliseconds, with higher traffic and richer data leading to higher bids. The IAB and PwC (2025) report notes that programmatic advertising alone accounted for more than $160 billion of the 2024 U.S. digital ad market, cementing its centrality in the profit code.

Direct-Sold Advertising and Sponsorships

Some outlets, particularly those with strong niche audiences, sell advertising space directly to brands. This allows them to bypass intermediaries and retain more profit. For example, TechCrunch frequently partners with technology conferences and startups for direct sponsorships.

Sponsored Content and Native Advertising

Sponsored stories blur the line between journalism and marketing. These pieces are designed to read like editorial content but are paid for by advertisers. While controversial, they are lucrative. BuzzFeed’s financial model heavily depended on such native content, allowing brands to tap into its viral distribution networks.

Affiliate Marketing

Articles that double as sales funnels—such as product reviews with embedded affiliate links—are now standard practice. Wirecutter, acquired by The New York Times, is a prime example, earning revenue whenever readers make purchases via its recommendations.

Subscriptions and Memberships

The most visible model is also one of the most strategically important. Subscription revenues provide predictable, recurring income. However, as Indiegraf (2024) noted in relation to this model, free access often continues alongside paid content, ensuring that even non-subscribers contribute to the data and advertising economy.

Taken together, these streams demonstrate that the formula of digital profits is not linear but circular: traffic generates data, data fuels monetization, and monetization finances further traffic acquisition.

3.4 Case Studies—From Giants to Niche Players

To see the formula in action, it is useful to examine case studies across the spectrum of digital publishing.

The New York Times

The Times represents a hybrid model where subscriptions dominate revenue but advertising and affiliate sales still play significant roles. With over 10 million digital-only subscribers as of 2025, the Times generates vast amounts of first-party data. Its acquisition of Wirecutter has allowed it to diversify revenue through affiliate marketing. Crucially, even non-subscribers remain part of the profit code, as their traffic supports advertising.

The Guardian

The Guardian’s “voluntary contribution” model has been widely studied. Unlike traditional paywalls, it allows free access but solicits reader donations. This model maximizes reach (traffic) while still building a base of paying supporters. Yet, The Guardian also depends heavily on advertising, which means it too must optimize for attention.

BuzzFeed (and its Collapse)

BuzzFeed’s story demonstrates the volatility of over-reliance on traffic and algorithmic distribution. Its viral model thrived on social platforms, but when Facebook altered its News Feed algorithm in 2018, BuzzFeed’s traffic and ad revenues plummeted. This case underscores the fragility of profit models tied too tightly to traffic alone.

African Digital Publishers

Smaller regional publishers across Africa illustrate the adaptability of the formula. Outlets like Africa Digital News and Daily Maverick in South Africa experiment with hybrid models: free access for reach, donations or memberships for core supporters, and programmatic ads for baseline revenue. These players may not achieve the scale of global giants, but they reveal how the same formula is localized to different markets.

3.5 Structural Implications—How the Formula Shapes Journalism

The formula of traffic, data, and profit does more than sustain publishing—it reshapes journalism itself.

Content Prioritization

Stories likely to generate high traffic are prioritized over those that serve purely civic functions. For example, celebrity scandals or lifestyle articles often eclipse investigative reporting because they produce more immediate engagement.

Algorithmic Dependence

Since much traffic is mediated by platforms like Google and Facebook, publishers shape their content to align with platform algorithms. This dependence raises questions of editorial independence.

Data-Driven Editorial Decisions

Editors now weigh not just journalistic merit but also predicted performance metrics. Articles may be rewritten, headlines tweaked, or visuals changed based on real-time analytics.

Inequalities Among Publishers

Larger outlets with the resources to invest in sophisticated data infrastructure dominate, while smaller publishers struggle to compete. The Gradient Group (2025) highlights this structural inequality, noting that while diversified revenue streams are growing, the concentration of ad spend among top publishers exacerbates the challenges for mid-size and local outlets.

This structural reality suggests that journalism is no longer shaped solely by editorial priorities or public need but increasingly by the demands of a digital economy optimized for traffic, data, and profit.

3.6 Conclusion – Cracking the Formula’s Code

The secret formula of digital profits—traffic, data, and monetization—explains why online journalism looks the way it does. It reveals why certain stories dominate headlines, why outrage spreads faster than nuance, and why publishers increasingly blur the line between journalism and commerce.

Traffic provides the foundation, data transforms chaos into order, and monetization mechanisms turn this system into profit. Together, these elements form a circular economy that sustains the industry but also distorts its civic mission.

As the IAB and PwC (2025) figures show, the revenues are staggering: hundreds of billions of dollars flow annually through this system. Yet, as the Broadstreet Ads (2024) and Gradient Group (2025) reports reveal, sustainability is uneven, and the formula creates as many vulnerabilities as strengths.

Understanding this formula is essential. Without it, readers remain under the illusion that journalism exists to serve them. With it, the hidden code becomes visible: a system where every headline, every click, and every data point is part of a meticulously engineered profit machine.

Part 4—The Algorithm Conspiracy

Editors no longer decide what you see—algorithms do, and their rules are written in code that no one outside the platforms is allowed to read.

4.1 Algorithms as the New Editors

In the analog age, journalism’s gatekeepers were human editors. They chose front-page stories, decided which voices deserved prominence, and curated a balance between public interest and commercial viability. In the digital era, however, this gatekeeping function has shifted dramatically. Algorithms now act as the silent editors of the internet, determining not just which stories are visible, but also how they are ranked, distributed, and amplified across billions of screens.

Platforms such as Google, Facebook, and TikTok rely on complex machine-learning models to optimize user engagement. Their algorithms decide which news links appear at the top of a search result, which headlines are promoted on social feeds, and which videos are placed on recommendation panels. These decisions, often invisible to users, exert immense influence over what the public perceives as important, urgent, or credible.

The central problem is opacity. Unlike traditional editorial processes, which could be critiqued or debated, algorithms operate as black boxes. As Hernandes and Corsi (2024) demonstrate in their comparative audit of Google’s search algorithm across Brazil, the UK, and the US, the ranking and visibility of news stories vary significantly across regions, raising concerns about diversity, bias, and the hidden shaping of public opinion.

The shift from editors to algorithms has transformed journalism into a dependent system. Newsrooms no longer control distribution—they must adapt to the mysterious logic of algorithmic platforms.

4.2 Hidden Rules: Reward and Punishment

Algorithms function like invisible referees, rewarding certain types of content while punishing others. The rules are rarely disclosed, yet their effects are unmistakable.

Reward Mechanisms:

- Content that generates high engagement—clicks, likes, shares, comments—is promoted.

- Multimedia-rich stories (videos, images, infographics) are favored over text-only reports.

- Stories aligned with trending topics are given prominence, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of virality.

Punishment Mechanisms:

- Stories flagged as “low quality” are suppressed.

- Publishers who fail to optimize for search engine optimization (SEO) are buried beneath rivals.

- Content deemed “too slow” in page load speed is penalized, regardless of journalistic merit.

These hidden rules create perverse incentives. Outlets tailor headlines for clickability rather than accuracy, prioritize speed over verification, and package serious reporting into snackable formats to please algorithms. As a result, journalism begins to mirror the demands of code rather than the needs of democracy.

The conspiracy lies not in a secret meeting of platform executives plotting against journalism, but in the silent, coded rules that systematically distort visibility. Hernandes and Corsi’s (2024) findings make this clear: algorithmic decisions can either amplify a wide diversity of voices or reduce news distribution to a narrow band of mainstream sources.

4.3 Case Study: Google’s Algorithm and News Diversity

Google’s search engine remains the single most important gateway to information. Studies estimate that more than 90% of online experiences begin with a search query. For news, this means that appearing on the first page of results—or better yet, in Google News—can make or break a publisher.

Hernandes and Corsi (2024) reveal troubling evidence in their audit: news visibility in Google’s rankings often skews toward large, well-established outlets, marginalizing smaller or independent publishers. In Brazil, for example, regional news organizations were frequently buried under national or international sources, reducing diversity and local representation.

This bias creates a feedback loop. Big outlets get more clicks, which signals to the algorithm that they are more authoritative, which then grants them even higher visibility. Smaller outlets, despite producing quality journalism, struggle to compete because the algorithm systematically deprives them of exposure.

In practice, Google is not neutral. It curates the flow of information, even if unintentionally, by embedding certain values into its ranking systems. This raises pressing questions: Who decides what counts as “reliable”? On what basis are these rankings justified? And how can accountability exist when the rules are proprietary trade secrets?

4.4 Beyond Google: Facebook, TikTok, and Algorithmic Power

While Google dominates search, social platforms such as Facebook and TikTok exert equally profound influence through algorithmic feeds.

Facebook’s News Feed

In 2018, Facebook shifted its algorithm to prioritize “meaningful social interactions” over publisher content. The result was a sharp decline in traffic to many news sites, forcing layoffs across the industry. Outrage-driven and sensational content, however, thrived because it triggered more user reactions and comments. This demonstrated how a single algorithmic tweak could reshape journalism worldwide.

TikTok’s “For You” Page

TikTok operates on an even more opaque recommendation system. Its algorithm learns rapidly from micro-interactions—pauses, rewatches, swipes—and feeds users increasingly personalized content. This model is exceptionally effective for entertainment but troubling for news. Studies have shown that politically charged or conspiratorial content can proliferate rapidly, outpacing fact-checked journalism. The opacity of TikTok’s system has raised alarms about foreign influence and election interference, given the platform’s Chinese ownership and global reach.

Cambridge Analytica Scandal

The infamous Cambridge Analytica case highlighted how algorithmic distribution could be weaponized. By harvesting Facebook data and targeting users with hyper-personalized political ads, the firm influenced voter behavior during the 2016 U.S. election and the Brexit referendum. The scandal underscored how algorithms, designed to optimize engagement, could be exploited to manipulate democratic processes.

Together, these cases illustrate a troubling reality: algorithms are not passive tools. They are active shapers of public discourse, capable of tilting entire societies toward outrage, polarization, or disinformation.

4.5 Structural Consequences for Journalism

The algorithmic system creates deep structural consequences for journalism as a profession and as a civic institution.

Dependence and Vulnerability

Publishers are locked into an asymmetrical relationship. While they produce the content, platforms control its distribution. A single algorithmic update can wipe out traffic overnight, as BuzzFeed and countless smaller outlets discovered.

Homogenization of Content

To appease algorithms, outlets adopt similar formats and strategies. Headlines become click-oriented, multimedia becomes mandatory, and coverage skews toward trending topics. The result is a homogenized media landscape where diversity of style and voice diminishes.

Erosion of Investigative Reporting

Investigative journalism, which requires time and resources but produces less immediate engagement, is structurally disadvantaged. Algorithms reward immediacy and virality, pushing long-form civic reporting to the margins.

Algorithmic Bias and Inequality

As Hernandes and Corsi (2024) highlight, algorithmic bias entrenches inequalities between large and small publishers. Independent, regional, and minority voices often struggle to gain visibility, weakening pluralism in the media ecosystem.

Democratic Risks

Most critically, algorithmic gatekeeping undermines democracy. When algorithms reward outrage and sensationalism, societies become polarized. When disinformation spreads more efficiently than truth, trust erodes. And when platforms refuse transparency, accountability becomes impossible.

4.6 Conclusion – Decoding the Algorithmic Conspiracy

The phrase “algorithm conspiracy” does not imply a secret cartel plotting against journalism. Rather, it captures the systemic distortion created when opaque code assumes the role of editor. Algorithms determine visibility, amplify certain voices, and marginalize others, all without transparency or accountability.

Hernandes and Corsi’s (2024) audit shows that even within a single platform like Google, outcomes vary across regions, undermining the idea of neutrality. Cases like Facebook’s News Feed overhaul, TikTok’s opaque recommendations, and Cambridge Analytica’s exploitation of data demonstrate the tangible consequences of algorithmic power.

The conspiracy lies in invisibility. Readers believe they choose their news. In reality, code decides before they even click. Newsrooms believe they publish for the public. In reality, they publish for algorithms, optimizing not for truth but for survival.

Decoding this conspiracy is essential. Unless algorithms are audited, made transparent, and regulated, journalism risks becoming a dependent arm of platform logic rather than a pillar of democracy.

The hidden code of online profits is incomplete without the recognition that algorithms are the ultimate brokers of attention. They are the silent editors of our time, and their conspiracy is that they shape the public sphere without ever being seen.

Part 5 —Programmatic Ads: The Silent Cash Machine

Every time a page loads, an invisible auction begins—your attention is sold in milliseconds, and news sites cash in silently.

5.1 What Programmatic Advertising Really Is

To understand the financial backbone of digital journalism today, one must grasp the concept of programmatic advertising. At its core, programmatic advertising is the automated buying and selling of ad space in real time. Unlike the traditional model where media companies negotiated directly with advertisers, programmatic relies on algorithms, data, and digital exchanges to auction attention in fractions of a second.

Here is how it works: when a reader clicks on a news article, the website instantly sends data about that visitor—location, device type, browsing history, and sometimes inferred interests—to an ad exchange. Advertisers then bid, in real time, for the right to display an ad to that specific user. Within milliseconds, the highest bidder wins, and the ad is displayed. The process is invisible to the reader but immensely profitable for publishers.

Programmatic advertising has become the dominant force in digital publishing. According to eMarketer (2024), digital publisher programmatic ad sales continued to grow in 2024, with incremental but steady increases that collectively represent billions in revenue. For publishers, this system provides efficiency, scale, and a continuous stream of income—hence its description as the industry’s “silent cash machine.”

5.2 The Auction House of Attention

Programmatic advertising transforms every webpage into an auction house of human attention. Unlike the fixed pricing of traditional advertising, where a half-page print ad had a known cost, programmatic operates on dynamic bidding. The value of a single impression varies depending on who the user is, what they have searched for, and how desirable they are to advertisers.

This personalization explains why programmatic is so effective. A financial services company may bid heavily to show ads to a middle-aged professional browsing investment articles but ignore a teenager watching sports highlights. The auction system ensures that publishers can maximize revenue by tailoring every impression to the advertiser most willing to pay.

As Grumft (2025) notes in its analysis of programmatic advertising trends for publishers, the industry is increasingly shifting toward data-driven precision. With advances in AI-driven targeting, every impression becomes more valuable because advertisers are paying not just for a page view, but for access to the right person at the right time.

The silent efficiency of this system explains why programmatic revenues now surpass direct-sold advertising for most digital publishers. The silent cash machine hums in the background, monetizing every scroll, every click, and every pause in front of an article.

5.3 How It Turns News Sites into 24/7 Money Pipelines

For publishers, the beauty of programmatic lies in its automation. Once ad slots are configured, they generate revenue continuously without human negotiation. This turns news websites into 24/7 monetization engines.

Every article—whether investigative reporting, breaking news, or lifestyle commentary—becomes a vessel for programmatic ads. Publishers need only focus on driving traffic; the programmatic system ensures that every visit is monetized. This explains why many outlets have adopted aggressive strategies to maximize page views: endless scrolling formats, click-driven headlines, and multi-page articles that multiply ad impressions.

NeworMedia (2025) highlights that programmatic systems are increasingly integrating with contextual and behavioral targeting tools, enabling publishers to extract more value per impression. For example, an article about electric vehicles can be programmatically matched with ads from car manufacturers, charging companies, or green technology brands. This contextual alignment boosts ad value and creates new monetization opportunities.

Even small and mid-size publishers benefit. While they cannot command the direct ad deals of major outlets, programmatic networks allow them to access global advertisers automatically. As a result, a niche African publisher writing about local politics can earn revenue from a multinational brand targeting demographics in that region.

Programmatic turns news sites into perpetual money pipelines, flowing day and night, regardless of time zones or editorial cycles.

5.4 Case Studies: From Global Giants to Niche Publishers

The New York Times

While The New York Times has emphasized subscriptions as its dominant revenue stream, programmatic advertising remains a significant component. Its vast traffic ensures that even incremental increases in programmatic rates translate into millions annually. The Times uses sophisticated audience segmentation to maximize ad value, demonstrating how even subscription-heavy outlets still rely on the silent cash machine.

BuzzFeed

BuzzFeed built much of its early empire on programmatic and native ads. Its viral model, dependent on clicks and shares, was perfectly suited to maximize impressions. However, its reliance on programmatic also made it vulnerable to algorithmic shifts on platforms like Facebook. When traffic collapsed, so too did the profitability of its ad pipeline.

Smaller African Publishers

For smaller regional publishers in Africa, programmatic provides access to revenue streams once unavailable. A site like Nairobi Chronicle, for instance, can join a programmatic exchange, instantly connecting with advertisers from across the globe. This democratization of access allows even small publishers to monetize traffic, though at lower rates compared to global giants.

Controversies and Cracks

However, programmatic is not without problems. Ad fraud—where fake traffic or bots mimic human visitors—remains rampant, siphoning billions from advertisers and undermining trust in the system. Brand safety scandals have also emerged, where programmatic ads from major companies appear next to extremist or disinformation content. For instance, in 2017, several multinational brands pulled ads from YouTube after discovering their ads were displayed alongside extremist videos.

These controversies highlight that while programmatic is efficient, it is also risky. Publishers can generate revenue without fully controlling where or how ads appear, exposing them to reputational harm.

5.5 Structural and Ethical Implications

The dominance of programmatic advertising has profound structural and ethical consequences for journalism.

- Incentivizing Clickbait

Because programmatic rewards traffic volume, publishers are incentivized to maximize clicks rather than prioritize quality. Headlines are often engineered for shock value or emotional impact to increase impressions. - Homogenization of Content

Programmatic algorithms often favor certain formats (fast-loading pages, mobile-first content, multimedia). This pressures publishers into adopting similar strategies, reducing diversity of style and voice. - Commodification of Audiences

Readers are not treated as citizens but as segments of data. Every click is a transaction, and every user becomes a product to be packaged and sold to advertisers. - Inequality Between Publishers

Large outlets with high traffic volumes earn the most, while smaller outlets struggle with lower CPMs (cost per thousand impressions). This exacerbates inequalities within the media ecosystem, as reported by Grumft (2025), which notes that publishers with strong first-party data see higher returns than those dependent solely on generic impressions. - Threats to Editorial Independence

When revenue depends on programmatic ads, editorial priorities shift toward content that maximizes monetization rather than serving democratic needs. Investigative journalism, which requires time and resources but generates fewer clicks, is structurally disadvantaged. - Ethical Concerns in Targeting

Programmatic relies heavily on user data. With increasing privacy concerns and regulations, the ethical dilemma of tracking user behavior for ad targeting becomes more urgent. The silent cash machine thrives on data extraction, raising questions about surveillance and consent.

5.6 Conclusion – The Silent Cash Machine Decoded

Programmatic advertising has revolutionized digital publishing. It has automated monetization, democratized access to advertisers, and turned every page load into revenue. For publishers, it provides a dependable stream of income that operates continuously in the background.

But this silent cash machine comes with trade-offs. It incentivizes click-driven content, homogenizes formats, and commodifies audiences. It creates vulnerabilities to ad fraud, brand safety scandals, and ethical concerns over privacy. Most critically, it risks subordinating journalism’s democratic role to the imperatives of algorithmic monetization.

As eMarketer (2024) and NeworMedia (2025) suggest, programmatic will continue to grow in 2025 and beyond, increasingly driven by AI, contextual targeting, and first-party data. The silent cash machine is unlikely to disappear—it will only become more efficient.

For journalism, the challenge is balance: leveraging the financial power of programmatic while resisting its corrosive effects on editorial independence and public trust. Without transparency, oversight, and ethical reform, the cash machine may continue to hum profitably—but at the cost of journalism’s soul.

Part 6—Affiliate Links & Sponsored Stories

Not every article is written to inform—some are designed to sell, and the line between journalism and commerce has never been thinner.

6.1 The Blurred Lines Between Journalism and Commerce

The modern media economy thrives on hybridity. Where once journalism and advertising were distinct domains—separated by clear “church and state” boundaries—today those lines blur into ambiguity. Affiliate links and sponsored content exemplify this convergence. Articles that appear to be independent reporting or consumer advice are often, in reality, commercial vehicles designed to generate revenue.

The business logic is undeniable. As advertising markets fragment and subscriptions grow only modestly, publishers are compelled to explore diversified revenue streams. The World Press Trends Outlook 2025 stresses that digital publishers increasingly rely on “other” revenue sources, including affiliates and sponsorships, to steady their financial base (WAN-IFRA, 2025). This trend transforms journalism into a hybrid product: part reporting, part commerce.

For the casual reader, however, the commercial underpinnings are often invisible. The affiliate link is embedded discreetly in a product review. The sponsored article is formatted to resemble an editorial piece. The illusion of neutrality persists even as financial incentives drive content.

This blurred boundary is not accidental—it is designed. Publishers benefit precisely because the commercial intent is hidden behind the authority of journalism. Yet this raises profound ethical questions about trust, transparency, and the future of editorial independence.

6.2 Affiliate Marketing: Journalism as a Sales Funnel

Affiliate marketing turns journalism into a sales funnel. The mechanism is straightforward: publishers earn a commission when readers click links and purchase products recommended in articles. On the surface, this model appears mutually beneficial. Readers gain useful recommendations, brands secure exposure, and publishers diversify revenue streams.

The financial stakes are significant. According to industry reports, affiliate marketing accounted for 15–20% of digital publishers’ e-commerce-related revenue in 2024, with steady growth projected through 2025 (Gradient Group, 2025). For publishers facing volatile ad markets, affiliate links provide a relatively stable income source.

One of the most famous examples is Wirecutter, acquired by The New York Times in 2016. Wirecutter specializes in product reviews and buying guides, monetized through affiliate commissions. In 2022 alone, it generated more than $70 million in revenue, demonstrating the profitability of this hybrid model. What looks like independent consumer advice doubles as a monetization machine.

Yet the model is not without pitfalls. The incentives embedded in affiliate marketing can subtly (or overtly) distort editorial judgment. Reviewers may favor products with higher commission rates, while articles may prioritize categories that attract lucrative affiliate deals rather than those most relevant to readers.

As Broadstreet Ads (2024) emphasizes, affiliate marketing is now one of the top five proven revenue models for digital publishers. Its rise indicates a structural shift: journalism no longer stops at informing readers; it nudges them toward commercial transactions.

6.3 Sponsored Content: Ads Disguised as Articles

If affiliate links are the hidden commission, sponsored content—sometimes branded as “native advertising”—is the disguised advertorial. These are articles funded by brands but formatted to look and feel like editorial content. The sponsorship may be disclosed in fine print, but the presentation blurs the line between journalism and marketing.

The appeal to publishers is clear. Sponsored content commands premium rates because it leverages the trust readers place in editorial environments. According to WAN-IFRA (2025), publishers worldwide increasingly rely on sponsorship-based models to supplement declining ad revenues. In some markets, sponsored content now accounts for 10–25% of publisher revenue, rivaling traditional display advertising.

BuzzFeed pioneered this model in the 2010s, partnering with brands to create viral quizzes, listicles, and features disguised as entertainment. The Guardian launched Guardian Labs, a branded content studio that works with corporate partners while maintaining journalistic style. Even niche African publishers have experimented with sponsored sections, often funded by NGOs, tech companies, or financial institutions eager to associate with credible journalism.

The risks, however, are manifold. When journalism carries commercial intent, trust erodes. Readers may question whether an investigative feature on climate change is influenced by an energy sponsor, or whether a technology review reflects genuine analysis rather than paid promotion. The ethical hazard is that journalism becomes indistinguishable from advertising—undermining its legitimacy as a democratic institution.

6.4 Case Studies: Wirecutter, BuzzFeed, and Global/Niche Publishers

Wirecutter (The New York Times)

Wirecutter epitomizes the affiliate model. With its rigorous product testing and trusted recommendations, it has built credibility while generating millions in commissions. Its integration into the Times portfolio demonstrates how legacy institutions adapt commerce models while leveraging journalistic authority. Yet the model has drawn scrutiny for conflicts of interest, especially when affiliate deals may bias recommendations.

BuzzFeed and Native Ads

BuzzFeed’s early success came from blurring editorial and advertising boundaries. Viral sponsored posts for brands like Coca-Cola or Netflix were often indistinguishable from standard BuzzFeed content. This strategy generated immense revenue but also criticism for eroding the line between journalism and marketing. Ultimately, BuzzFeed News shuttered in 2023, revealing both the power and fragility of a business model heavily reliant on sponsorships and virality.

Guardian Labs

The Guardian has attempted a more transparent approach through Guardian Labs, openly labeling sponsored content while maintaining editorial oversight. This model provides steady income while attempting to preserve trust, though critics argue that even transparency cannot neutralize the fundamental conflict of interest.

African Publishers

Regional publishers in Africa, often under-resourced, have embraced affiliate and sponsored models out of necessity. Outlets such as Africa Digital News rely on sponsored sections funded by development organizations or corporate partners. These arrangements provide vital income but raise concerns about editorial capture, especially in politically sensitive environments.

Together, these cases illustrate the double-edged nature of affiliate and sponsored content: financially stabilizing but ethically precarious.

6.5 Ethical and Structural Implications

The rise of affiliate links and sponsored content carries structural consequences that reshape journalism itself.

Erosion of Trust

Trust is journalism’s most valuable asset. When readers perceive content as covert advertising, credibility suffers. Transparency labels such as “sponsored” or “affiliate link” help, but many readers ignore or overlook them.

Distorted Editorial Priorities

Content increasingly reflects commercial imperatives. Product reviews proliferate because they are monetizable, while resource-intensive investigative reporting languishes. Newsrooms may prioritize coverage areas aligned with sponsor interests, narrowing editorial diversity.

Audience as Consumer

The framing of readers shifts from citizens engaged in democracy to consumers targeted for conversion. Journalism becomes not just about informing the public but about nudging them through a sales funnel.

Revenue Inequality

Large publishers benefit disproportionately. The Gradient Group (2025) notes that outlets with brand recognition and strong traffic see higher returns from affiliate and sponsorship deals, while smaller publishers struggle to secure meaningful partnerships. This exacerbates inequalities in the media ecosystem.

Ethical Grey Zones

The “hidden commission” of affiliate links raises fundamental questions about consent. Readers may be unaware that their clicks generate revenue, creating a transaction without transparency. Sponsored content further complicates this, embedding commerce into journalism in ways that can manipulate audience perception.

6.6 Conclusion – Journalism in the Age of Commerce

Affiliate links and sponsored stories embody the commercialization of journalism in the digital age. They offer publishers much-needed revenue diversification in a landscape where traditional advertising falters and subscriptions plateau. As Broadstreet Ads (2024) notes, these models are among the most proven revenue strategies for digital publishers. As WAN-IFRA (2025) emphasizes, they have helped stabilize global publishers in turbulent times.

Yet they also represent a profound transformation in the identity of journalism. Articles no longer exist solely to inform; they exist to convert. Headlines double as sales pitches. Stories become disguised advertisements. The risk is that journalism’s democratic mission erodes under the weight of commercial imperatives.

The challenge ahead is balance. Transparency, clear labeling, and ethical codes can mitigate harm, but they cannot erase the structural reality: the age of journalism as pure public service is over. In its place stands a hybrid institution—part watchdog, part salesperson—where the lines between informing and selling grow thinner each day.

Part 7—Paywalls and Membership Illusions

Scarcity is manufactured, loyalty is monetized — the illusion of exclusivity is journalism’s latest business model.

7.1 How Scarcity is Manufactured to Sell Exclusivity

In the digital environment, content is abundant. News, analysis, commentary, and multimedia flood the internet in seemingly infinite quantities. Yet paradoxically, publishers increasingly create scarcity by erecting paywalls. The logic is strategic: what is ubiquitous cannot be monetized, but what is scarce can be sold.

Paywalls manufacture exclusivity. By restricting access to certain stories—especially investigative reports, long-form features, or premium newsletters—publishers transform information into a commodity. This scarcity signals value, positioning journalism not just as a public good but as a private product.

According to the Digital News Report 2025, more than 23% of online news consumers globally now pay for digital news, whether through subscriptions, donations, or memberships (Newman, 2025). This figure is modest compared to music or film streaming but represents steady growth. Publishers lean on this trend as traditional ad revenues stagnate.

Scarcity also plays a psychological role. When readers encounter a locked article, they perceive the content as valuable precisely because it is restricted. This engineered scarcity transforms curiosity into a purchase decision. The strategy is less about blocking access and more about cultivating desire.

7.2 The Psychology of Locking Content Behind Paywalls

The success of paywalls hinges not only on economics but also on psychology. Publishers leverage behavioral triggers to convert casual readers into paying customers.

Loss Aversion: Humans are more motivated to avoid losing something than to gain something new. When a reader begins an article only to be blocked by a paywall, they feel a sense of loss. The frustration nudges them toward subscription.

Exclusivity: Paywalls tap into the desire for status. Being a subscriber is framed as belonging to an exclusive community with privileged access.

Recurring Value: Publishers frame subscriptions as investments rather than costs. By emphasizing daily updates, exclusive newsletters, or archive access, they highlight continuous returns on payment.

Indiegraf (2024) points out that subscription models often rely on tiered offers—basic free access, mid-level paid access, and premium memberships. This structure exploits consumer psychology by creating contrast: the free tier seems insufficient, while the premium tier makes the mid-level option appear affordable and reasonable.

Paywalls are, therefore, as much about behavioral design as they are about finance. They are less about restricting access than about engineering desire and loyalty.

7.3 Membership Models: From Subscribers to Loyalists

While subscriptions are transactional, memberships are relational. Membership schemes invite readers to identify with the mission of a news organization, not just its content. This shift reframes readers not as buyers but as supporters, even co-creators of journalism.

Membership models emphasize transparency, community, and shared values. Outlets like The Guardian explicitly appeal to readers’ sense of civic duty, asking them to “support independent journalism” rather than buy content. This moral framing taps into altruism, solidarity, and loyalty.

According to the State of Publisher Revenue Streams in 2025, memberships are increasingly vital for publishers with smaller but highly engaged audiences (Gradient Group, 2025). For niche or local outlets, memberships provide stability by fostering loyalty among core readers, even if overall traffic is modest.

The psychological power of membership lies in identity. Subscribers consume; members belong. The difference is crucial, as belonging fosters retention, turning casual readers into lifelong loyalists.

7.4 Case Studies: NYT, Guardian, and Local Publishers

The New York Times

The New York Times exemplifies the success of subscription paywalls. With over 10 million digital-only subscribers by 2025, it has proven that readers will pay for quality journalism at scale (Newman, 2025). The Times uses a metered paywall, allowing limited free access before requiring payment, effectively balancing reach with monetization.

The Guardian

The Guardian takes a different approach, eschewing hard paywalls in favor of a voluntary contribution model. Readers are reminded that The Guardian remains free but are encouraged to support financially. This model has been remarkably successful, generating hundreds of thousands of voluntary memberships worldwide. It demonstrates that transparency and moral appeals can rival hard restrictions.

Local and Niche Publishers

Smaller outlets, including regional African publishers, often face greater challenges. Disposable income is lower, and readers expect free access. For example, attempts by certain South African digital publishers to implement hard paywalls have met resistance, with readers simply migrating to free alternatives. As a result, many local publishers rely on hybrid models: limited free access, voluntary donations, or “soft” paywalls combined with advertising.

These cases illustrate the diversity of approaches. There is no universal model; success depends on scale, audience demographics, and brand trust.

7.5 Structural and Ethical Implications of Paywalls

Paywalls and memberships stabilize journalism financially but raise profound ethical and structural questions.

Democratic Exclusion

If critical journalism is locked behind paywalls, access becomes stratified. Wealthier readers gain access to quality information, while poorer audiences are left with free, often lower-quality alternatives. This deepens the digital divide and undermines journalism’s democratic mission.

Global Inequalities

In emerging markets, paywalls often fail. Newman (2025) notes that willingness to pay for news is concentrated in wealthier countries. In much of the Global South, disposable income is too low, and readers prioritize free access. This raises questions about whether paywalls entrench global information inequalities.

Erosion of Public Service Ethos

Memberships may preserve access, but they also reframe journalism as a commodity supported by loyalty rather than a universal right. While financially viable, this risks redefining the identity of journalism as a private good rather than a civic duty.

Editorial Priorities

Paywalls can distort editorial decisions. Publishers may prioritize content that attracts paying subscribers—often lifestyle, opinion, or specialized analysis—over hard news or investigative reporting that serves broader public interest but draws fewer subscriptions.

Psychological Manipulation

The use of behavioral nudges—such as loss aversion or exclusivity framing—raises ethical concerns. Are readers freely choosing to support journalism, or are they being psychologically engineered into compliance?

As Indiegraf (2024) notes, the subscription model is not neutral—it shapes not only revenue streams but editorial priorities and audience relationships.

7.6 Conclusion – The Illusion of Access

Paywalls and memberships embody the paradox of digital journalism. On one hand, they represent innovative solutions to financial crises, allowing publishers to stabilize revenue and reduce dependence on volatile advertising markets. On the other hand, they manufacture scarcity, stratify access, and risk undermining journalism’s democratic mission.

The illusion lies in access. While publishers frame paywalls as gateways to exclusivity and quality, they are fundamentally mechanisms of exclusion. Memberships, meanwhile, foster loyalty but blur the line between civic support and commercial transaction.

As the Gradient Group (2025) observes, diversified revenue streams are essential for publisher survival. Yet, unless access inequalities are addressed, paywalls may entrench a two-tiered information ecosystem: one for the wealthy who can afford subscriptions, and another for the rest, reliant on free but often lower-quality content.

The challenge is balance. Can journalism monetize without betraying its civic role? Can exclusivity coexist with universality? Unless these questions are confronted, paywalls and memberships will remain powerful but deeply problematic illusions in the evolving code of digital profits.

Read also: Cancer Prevention Secrets Buried By Corporate Interest

Part 8 —The Business of Outrage

The angrier you are, the richer they get—because outrage is the fuel that prints digital money.

8.1 Outrage as the Most Profitable Emotion Online

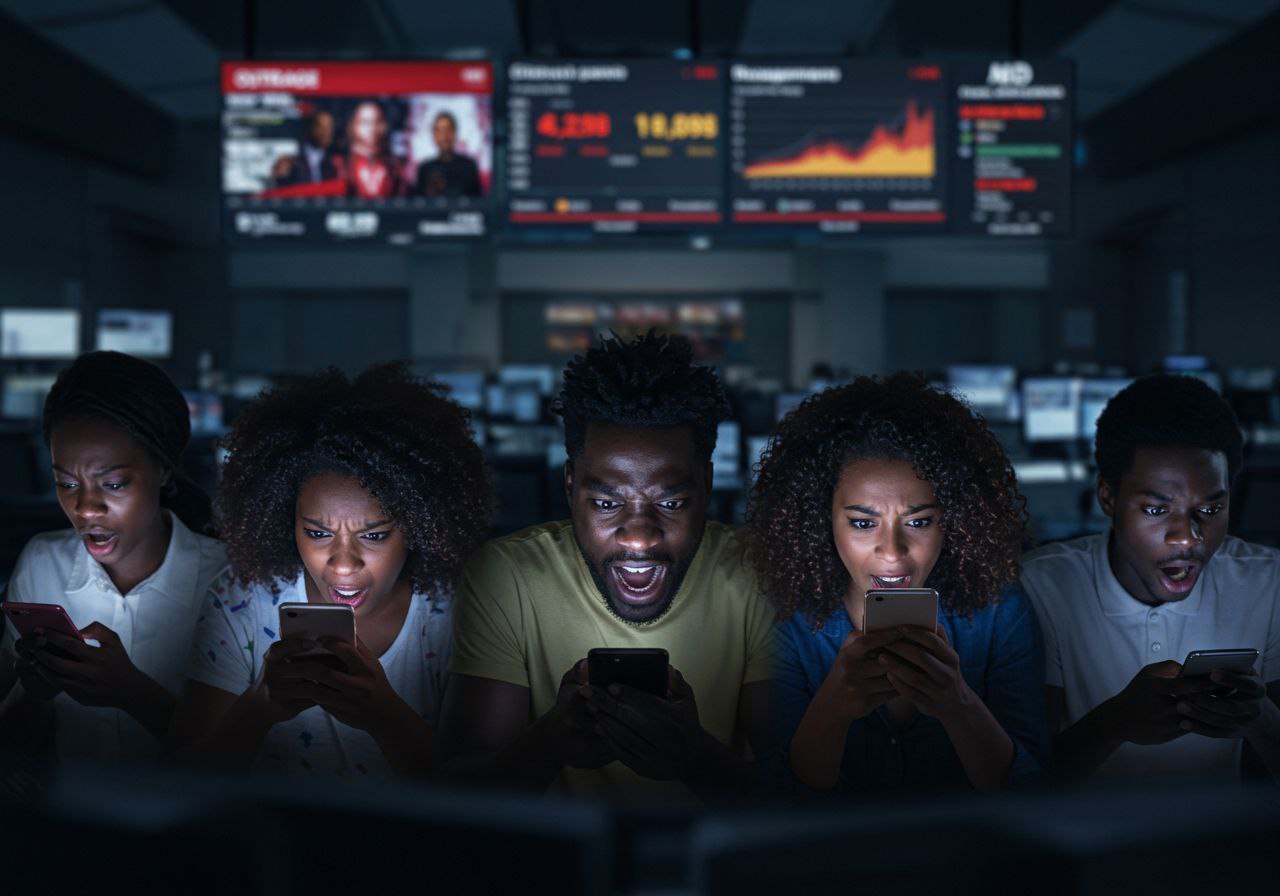

In the digital economy of attention, not all emotions are equal. Joy sparks fleeting engagement. Curiosity invites a click but not always a share. Outrage, however, is sticky, viral, and immensely profitable. When audiences feel anger or indignation, they are far more likely to comment, share, and react intensely. This produces spikes in traffic, more ad impressions, and higher engagement metrics—precisely the outcomes that both publishers and platforms monetize.

Outrage is therefore not merely a byproduct of journalism or social media—it is engineered, optimized, and commodified. Publishers design headlines that provoke fury. Platforms amplify posts that trigger indignation. The result is an economy where rage is no longer a political or cultural phenomenon alone; it is a revenue stream.

Research from Tulane University (2024) shows that “rage clicks”—instances where users engage with content primarily because it angers them—are particularly powerful drivers of social media activity. Political outrage, in particular, fuels higher engagement rates, outperforming neutral or even positive content. Outrage, in other words, is digital gold.

8.2 The Psychology of Anger, Fear, and Engagement

Why is outrage so potent? The answer lies in psychology.

Evolutionary Roots: Anger and fear are primal survival mechanisms. Humans are wired to respond intensely to perceived threats. Online, these instincts are hijacked by headlines, images, and narratives that frame issues as dangerous, unjust, or offensive.

Emotional Contagion: Anger spreads quickly in social networks. When one user posts an indignant comment, others pile on, escalating the emotional intensity. The viral quality of outrage makes it especially attractive to platforms seeking engagement.

Moral Outrage: Outrage is particularly powerful when tied to morality—issues framed as right versus wrong, good versus evil. This explains why political, cultural, and identity-based stories generate disproportionate attention.

As Northwestern University (2024) shows, misinformation exploits these dynamics. False or misleading content often leverages outrage to spread faster than fact-based reporting. Anger amplifies visibility, regardless of accuracy. This creates a perverse incentive: the more enraging the content, the more likely it is to dominate feeds, even if it is false.

8.3 Rage-Click Economics: How Platforms and Publishers Monetize Fury

At the heart of the business of outrage is monetization. Every click, comment, and share triggered by anger translates into revenue—both for publishers and for platforms.

Publishers’ Incentives

For publishers, outrage headlines generate more traffic, leading to higher programmatic ad revenues. A headline like “Politician X DESTROYS democracy” or “Outrage as Company Y betrays customers” drives far more engagement than neutral phrasing. This is not accidental—it is design. Newsrooms track engagement data and quickly learn that outrage outperforms nuance.

Platforms’ Incentives

Platforms like Facebook, Twitter/X, and TikTok have even greater incentives. Their business models rely on keeping users engaged for as long as possible. Outrage, with its addictive cycle of anger and validation, achieves this. Tulane University’s (2024) findings on political outrage confirm that social media algorithms reward fury because it sustains user attention and, by extension, ad exposure.

One striking example is Facebook’s weighting of reactions. Between 2017 and 2020, the platform reportedly gave five times more weight to “angry” reactions than likes in determining algorithmic reach. Posts that triggered anger therefore spread further, regardless of content quality. While Facebook later adjusted the weighting after criticism, the episode reveals how deeply outrage was baked into the platform’s logic.

The Outrage Feedback Loop

The cycle is self-reinforcing. Outrage drives engagement → engagement drives visibility → visibility drives outrage. Publishers learn to feed the loop, crafting content optimized for fury. Platforms refine algorithms to reward the same. The loop generates profits for all actors—except, arguably, the public.

8.4 Case Studies: Outrage Headlines, Political Polarization, and Viral Misinformation

U.S. Political Elections

Outrage has played a central role in shaping political communication online. During the 2016 and 2020 U.S. elections, headlines designed to provoke indignation dominated feeds. Both legitimate outlets and misinformation networks leveraged anger to drive visibility. Outrage became not just a political strategy but a commercial one, as engagement translated into advertising dollars.

Misinformation Virality

Northwestern University’s (2024) research highlights that misinformation thrives on outrage. False stories that provoke anger—such as fabricated scandals or exaggerated threats—spread faster than corrections or factual reports. Outrage acts as an accelerant, ensuring that misinformation circulates widely before fact-checkers can intervene.

Twitter/X Outrage Cycles

On Twitter (now X), outrage functions as a perpetual engine of virality. Trending topics often center around scandal, insult, or political controversy. Each cycle produces spikes in user engagement and platform activity. While advertisers sometimes express discomfort with toxic discourse, the overall effect sustains the platform’s attention economy.

Cultural Outrage Headlines

Publishers have increasingly leaned into cultural outrage—covering divisive issues such as gender debates, celebrity scandals, or symbolic controversies. These stories generate intense but short-lived spikes in traffic, illustrating how outrage is monetized even outside the political domain.

Together, these cases show how outrage is commodified across contexts—political, cultural, and social—always with the same outcome: profit.

8.5 Ethical and Democratic Implications

The monetization of outrage has profound consequences that extend beyond journalism into the fabric of democracy itself.

Polarization

By amplifying outrage-driven content, platforms contribute to social and political polarization. Citizens are constantly exposed to stories that provoke anger against opposing groups, deepening divisions.

Erosion of Trust

When audiences sense that outrage is being exploited for profit, trust in media declines. Journalism begins to resemble a performance designed to provoke rather than inform.

Misinformation Advantage

Because outrage spreads regardless of truth, misinformation gains an advantage in the attention economy. Fact-based reporting, which is often calmer and less sensational, struggles to compete. Northwestern University’s (2024) findings underscore how misinformation exploits this structural weakness.

Psychological Harm

Outrage addiction has mental health implications. Constant exposure to anger-inducing content increases stress, anxiety, and feelings of helplessness. Users are trapped in cycles of indignation that benefit platforms financially but harm individuals socially and emotionally.

Ethical Complicity

Both publishers and platforms face ethical questions. Are they merely responding to audience demand, or are they actively engineering outrage for profit? As Tulane University (2024) indicates, outrage is not neutral—it is cultivated. Responsibility therefore lies with those who design headlines and algorithms to maximize fury.

8.6 Conclusion – Outrage as Currency

The business of outrage reveals one of the most troubling dimensions of the hidden code of online news profits. Outrage is not accidental—it is intentional, cultivated because it is profitable. Publishers design for rage clicks; platforms amplify them because they sustain engagement. The cycle transforms anger into money, turning democracy’s emotional volatility into an economic asset.

Tulane University’s (2024) research demonstrates the centrality of outrage in driving online engagement. Northwestern University’s (2024) findings reveal how misinformation weaponizes this emotional economy. Together, they show that outrage is not simply a cultural problem—it is a structural feature of the digital attention economy.

The illusion of journalism as a neutral conveyor of facts is pierced here most clearly. The headlines we consume, the posts we see, the stories that dominate our feeds are shaped less by civic duty and more by the cold calculus of profit. Outrage has become currency, and every angry click is coin in someone else’s pocket.

Part 9—The Marketplace of Eyeballs

Your attention is the oil of the digital age—every glance, scroll, and click is drilled, refined, and sold in hidden markets you never see.

9.1 Traffic Sold Like Oil in a Hidden Market

The modern internet is built upon an invisible economy. What appears to be a seamless flow of free content is, in truth, a sprawling marketplace where human attention is bought, sold, and traded with ruthless efficiency. Just as barrels of oil were the dominant commodity of the 20th century, eyeballs—the quantified units of attention—are the defining commodity of the 21st.

Every time a reader visits a news site, scrolls a feed, or pauses on a video, they enter this marketplace. In the milliseconds it takes for a webpage to load, their attention is auctioned off in real time to the highest bidder. Advertisers compete for impressions, publishers sell access to their audiences, and platforms broker the trade. This hidden marketplace underpins billions in revenue but remains largely invisible to the everyday user.

Publishers themselves have often described traffic as their “inventory.” Unlike physical goods, however, this inventory is replenished instantly and endlessly. Each visit produces new eyeballs to be monetized. The greater the traffic, the larger the pool of inventory a publisher can offer. It is here that the metaphor of oil becomes precise: attention, like crude oil, is extracted, refined into measurable units, and sold in global markets.

The challenge, however, is that unlike oil, eyeballs are volatile. Their value fluctuates by geography, platform, device type, and even time of day. A U.S. visitor reading a financial article may command a $25 CPM (cost per thousand impressions), while a visitor from sub-Saharan Africa reading entertainment content may fetch less than $1 CPM. The marketplace is dynamic, global, and stratified.

Understanding this hidden economy is not merely about critique—it is about strategy. Publishers who master the dynamics of the eyeball marketplace can transform their operations into lucrative ventures. Those who ignore it risk obsolescence.

9.2 Understanding CPM: The Currency of Eyeballs